Looking Back, September 2025

By Mark Albertson

Part II: Army Aviation and its, Magna Carta

December 1961, the 8th Transportation Company (Light Helicopter) and the 57th Transportation Company (Light Helicopter) had arrived in Vietnam. These were followed in January by the 93rd Transportation Company (Light Helicopter). Two developments were evident here: America’s commitment to Saigon; and, the Airmobility Concept was on trial. Only the troops to be shuttled were not going to be American, but instead, those of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Meanwhile events in the United States proceeded apace . . .

. . . with American helicopters and Army aviators deployed, testing a concept without an accepted doctrine, official Washington, it seemed, was willing to accommodate the Army.

At the same time, the Air Force was certainly not ignored by the change in regimes in the White House. 1961 saw an expansion in strategic airlift capability, including an increase in the fleet of C-130s. Cargo versions of the KC-135 tanker, effecting the development of the C-141 cargo transport showed Air Force involvement in Flexible Response.[1] Be that as it may, the Army was wasting no time acting on its Magna Carta.

Also in 1961, Clifton von Kann, recently named Director of Army Aviation, scheduled a briefing with Secretary McNamara on Army Aviation and the importance of tactical aerial assets for the Ground Forces. “McNamara indicated that the briefing helped him to see Army Aviation in a new light and he requested additional paperwork.”[2]

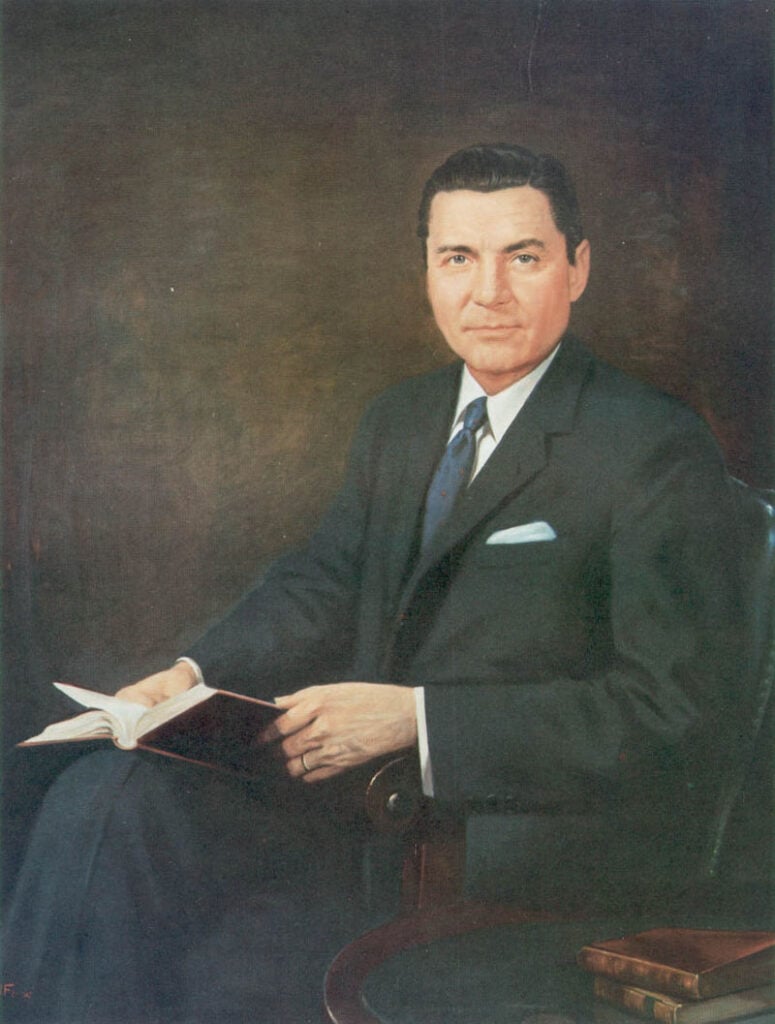

Robert McNamara was the eighth Secretary of Defense, 1961-1968. He served two Presidents: John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. A U.S.A.A.F veteran in World War II, he favored the Army’s use of aircraft for the movement of troops. He ordered the Secretary of the Army, Elvis J. Stahr, to see to it that the Army proceeded in the direction of Airmobility.

A mover and shaker behind the scenes was Robert R. Williams, a West Point grad and a member of the Class Before One and, the first Master Aviator. Williams had been, for all intents and purposes, a political insurgent for the founding principle of Army Aviation, the Air Observation Post.

Following the defeat of the Axis Powers, Williams was sent by the Army Air Forces to Europe, so as to canvass Air Force officers and Ground Forces commanders with regards to the Army Ground Forces retaining their organic aerial assets. “General Hoyt S. Vandenburg for example, felt that such an arrangement would permit the Army to convert its aircraft into close support fighter-bombers and airlift aircraft; others, such as Lauris Nordstad, felt that the atomic bomb had rendered the Army essentially irrelevant.”[3]

Williams, too, was on the McNamara staff and, from the inside, helped to channel the office of the Secretary of Defense towards nodding favorably in the direction of Army Aviation. This resulted in a pair of missives penned by the Secretary of Defense on April 19, 1962:

1) “Memorandum for the Secretary of the Army: Subject: Army Aviation.” And . . .

2) . . . “Memorandum for Mr. Stahr.”

Both directives compelled the Secretary of the Army, Mr. Elvis J. Stahr, to proceed in the fashion outlined above. The latter ordered the Army to take advantage of recent developments in technological advances in aviation to effect improvement in aerial tactical mobility, noting it as a “’bold new look’ at land warfare mobility,” while the former was a more general directive requiring the Army to effect positive changes in tactical mobility.[4]

Secretary of the Army, Elvis J. Stahr, 1961-1962, was a lieutenant-colonel in the Army during World War II. He carried out McNamara’s direction ordering the Army to formalize the Airmobility Concept. Stahr later became the President of the National Audibon Society.

This culminated, of course, in the Tactical Mobility Requirements Board, created by the United States Continental Army Command, May 3, 1962. Total staff amounted to 199 officers, 41 enlisted and 53 civilians.[5]

Lieutenant General Hamilton H. Howze, commander of the XVIII Airborne Corps at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, was pegged to chair what would popularly be known as the Howze Board.

Per the orders of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Hamilton H. Howze will chair the Tactical Mobility Requirements Board, AKA, the Howze Board and formalize in Airmobility in the United States Army.

Per the directive of General Herbert Powell, of the Continental Army Command, the final draft of the board’s findings was to be submitted to the Secretary of Defense by August 20 to accommodate Mr. McNamara’s deadline of September 1. A caveat here, though, was the voluminous nature of the report, which Howze questioned. The Department of the Army asserted that it should be able to fit neatly into an Army footlocker. And, of course, 300 copies were required. To fulfill such a paper chase, the printers at the Adjunct General Department stated that to produce 300 copies of the report that could fit into an Army footlocker demanded that it have the report no later than August 1, so as to accommodate the August 20 deadline. So the window of constraint was quite obvious here.[6]

The Board consisted of a review committee, composed of 17 officers and five civilians; together with an advisory panel with two members and a secretariat. Board secretary to General Howze was Colonel John Norton. Within the body of the memorandum addressed personally to Secretary of the Army Stahr, were individuals named by Secretary of Defense McNamara, who would be on the review committee chaired by General Howze and/or the secretariat: Besides Howze, Brigadier General Delk M. Oden, Brigadier General Walter B. Richardson, Colonel Robert R. Williams, the aforementioned Colonel John Norton, Colonel A.J. Rankin, Mr. Frank A. Parker, Dr. Edwin W. Paxson and Mr. Edward H. Heineman.[7] In addition, the commanding general of The Infantry Center, the special assistant to the Chief of Staff for Special Warfare and Brigadier Edward L. Rowney of the 82nd Airborne Division, were attached to the review committee. The Board would be settled at Fort Bragg in a school facility set aside as the headquarters.

Much of the work associated with the Tactical Mobility Requirements Board was done by seven working committees, from May 5 to June 21, 1962, and were as follows: Operations Research; Field Tests; Tactical Mobility; Firepower; Logistics Operations and Logistics Support; Reconnaissance; Security and Target Acquisition; and, Programs, Policy and Budget. On the heels of which were eight working groups, June 22 through July: Logistics Forces; Combat Force; Counterinsurgency; Strategic Area; Operations Research; Long Range; Field Tests; concluding with, Programs, Policy and Budget.

General Howze was not only President of the Board, but Chairman of the Steering and Review Committee as well. In addition to General Howze, seven other officers and six top level civilians originally composed the Steering Review Committee. These included Major General Ben Harrell, Major General William B. Rosson, Brigadier General John J. Lane, Brigadier General Delk M. Oden, Brigadier General Robert R. Williams, Colonel William M. Lynn, Jr., Dr. Jacob A. Stockfisch, Dr. Edwin W. Paxson, Eugene Vidal, Fred Wolcott, Frank A, Parker and Edward H. Heineman. Mr. Parker, General Rowney and Colonel Lynn also served as chiefs of working committees. Other senior board members (eventually added to the Steering and Review Committees) were named working committee chiefs—Major General Clifton von Kann, Major General Norman H. Vissering, Brigadier General Frederic W. Boye, Jr., and Brigadier General Walter B. Richardson.[8]

“The Air Force sent down a brigadier general to act as a monitor. He was privileged to see all the tests and exercises and could review anyone he chose, but we did not invite him to sit with the steering committee, and all the subcommittees were privileged to exclude him. This, in retrospect, seems regrettable, but in some sensitive areas, frank debate would have alarmed the Air Force and that admirable establishment really needed no additional agitation.”[9]

Perhaps in an effort, though, to foster better service relations, Deputy Secretary of Defense, Roswell L. Gilpatric, on May 8, 1962, that in the support of Army efforts wanted to make sure that air transport was available when requested by the Board. Such as a squadron of C-130s “which would provide the Air Force an opportunity to sell its services and capabilities.”[10]

Howze further explains in his book that in preparation Army Intelligence was petitioned for the latest intelligence on doctrine and capabilities of the Warsaw Pact as well as the People’s Republic of China. Weapons experts, designers and scientists were vetted for weapons types expected for the period 1963-1975, including opinion from the newly minted Combat Developments Command. Robert R. Williams was sent with a team to Southeast Asia to assess the potential of Army Aviation in such an environment; and Army logistics experts, in accordance with civilian equivalents from a dozen aircraft companies to advise on the current capability of the Army aircraft support system and its potential.[11]

Howze, added, that some 400 letters were posted to officers, those on active duty as well as those who had retired, for their expertise. Another 300 letters or more were forwarded to airframe, engine, armaments and electronic firms for their input, creating in essence, a reference source of unquestioned value, as well as being a sales pitch for companies to consider Army Aviation as a viable market.[12]

“Two agencies under contract with the Army, Research Analysis Corporation (R.A.C.) and Technical Operations Incorporation (C.O.R.G.), did studies and analysis for use as requested. Rand Corporation and Stanford Research provided several analysts and scientists for consultation and evaluation of committees at work.”[13]

Computer simulations, together with actual field work, saw Airmobility challenged through four battle models: A Warsaw Pact attack on Western Europe; versus Chinese Communist Forces in Asia (obviously the stalemate of the Korean War was still fresh in the minds of the planners); and, the blunting of threats to Africa as well as Central and South America. And, of course, the Army’s choice of vehicle to carry forward Airmobility . . . the helicopter.

The Howze Board released its finding on August 20, 1962. From the viewpoint of history, a fascinating perspective arises: The Army’s attempt to base Airmobility on the helicopter during the 1960s was not too unlike the transition in mobility from the horse to the truck and tanks, during the 1920s and 1930s. However an important factor to appreciate here was that the United States was not the only power wrestling with mobility during that period leading up to the continuation of the 1914 conflict, sharing the stage with Germany, Britain and the Soviet Union. . . And the living embodiment of the criteria set forth by the Howze Board . . . the 11th Air Assault Division (Test).

* * * * *

11th Air Assault Division (Test)

The resolution of the Tactical Mobility Requirements Board set the stage for that next step in the quest to implement Airmobility. Lieutenant General Hamilton H. Howze urged the conversion of the 82nd Airborne into the air assault division as projected by his committee. He was overruled by Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, who instead authorized an expansion of Army personnel for fiscal year 1964, from 960,000 to 975,000.

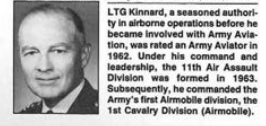

McNamara’s authorization would enable the new unit to be organized from scratch. And on January 7, 1963, orders were issued to commence the operation. The 11th Air Assault Division (Test) was activated at Fort Bragg, North Carolina on February 15, 1963. In command was Brigadier General Harry W.O. Kinnard.[14]

General Harry W.O. Kinnard, commanding officer of the 11th Air Assault Division (Test).

11th Air Assault Division (Test) had its roots in the 11th Airborne Division. The “Angels” were activated on February 25, 1943, seeing action in the Philippines at Leyte and Luzon.

With the cessation of hostilities, the 11th Airborne landed in Japan as part of the postwar Army occupation of the Japanese home islands.[15] The “Angels” were deactivated on June 30, 1958; reactivated briefly on February 1, 1963, then re-designated 11th Air Assault Division (Test) on the 15th.

Among those units attached to the 11th A.A.D early on were those from the 187th Infantry Regiment;[16] as well as the 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion.[17] In addition to the activation of the 11th A.A.D, a logistics support unit was organized in the name of the 10th Air Transport Brigade.[18]

Training focused on air assault; drilling infantrymen on the new concepts of joining combat and engaging the enemy. Provisional supply bases of fuel and stores were made available and organized to keep pace with helicopter units on a fluid battlefield.

Hence the concept of F.A.R.P. or the Forward Arming and Re-Fueling Point.[19]

Another innovation was artillery fire support for landing zones. This included rocket-firing helicopters to support attacks by air assault troops; bolstered, in part, by experience gleaned from Army Aviation support of Army of Republic of Vietnam (A.R.V.N.) units in Southeast Asia.[20]

In September 1963, Air Assault I exercises at Fort Stewart in Georgia, saw the Airmobility Concept put through its paces on the battalion level of operations. The following year, October 1964, Air Assault II was conducted and by comparison, an exercise on a far grander scale.

Air Assault II sprawled across two states, the Carolinas, taking in some 4,000,000 acres. 35,000 troops were committed, with the 11th A.A.D. squaring off against the 82nd Airborne Division; the latter engaged in the role of an enemy conventional force as well as that of insurgent opposition.

The first of the four weeks slated for the exercise was conducted during a hurricane, “Isabel.” Flying conditions were abysmal; a swirling vortex of wind, rain and fog, leaving many aviators peering through windscreens opaque as a bucket of mud.

Yet 120 helicopters managed to shuttle an infantry brigade 100 miles through the ire of Mother Nature.

General Kinnard summed it up thus: Beyond what I believe to be its capabilities to perform roles normal to other divisions, I am even more impressed by what I feel is its ability to perform in unique ways beyond the abilities of other divisions.

For example, in a low-scale war, I believe it can exert control over a much wider area and with much more speed and flexibility and much less concern for the problems of interdicted ground communications or of difficult terrain.

In higher scales of war, I see this division an unparalleled reserve or screening force capable of operating over very large frontages.

By properly picking times, places and methods, I believe it can also operate with devastating effect against the rear of the enemy.

Faced with the threat or use of nuclear weapons, I believe it can widely disperse, and yet, when required, quickly mass, even over irradiated ground, blown down forests or rubled cities, strike an enemy, then disperse again.[21]

Kinnard’s men will get a chance to showcase their training in Southeast Asia. Up to 1965, airmobility consisted, for the most part, of Army aviators ferrying South Vietnamese troops into action against the Viet Cong.

But Hanoi was raising the ante. With the Gulf of Tonkin incident, it was certain as sunrise that the first string American air assault troops would be coming off the bench to spell A.R.V.N.’s second eleven.

On July 1, 1965, 11th Air Assault Division (Test) was reflagged as the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) and 27 days later, President Johnson ordered the airmobile division to Vietnam.[22]

In November, at Ia Drang, 1st Cavalry air assault forces took their peacetime training into action against North Vietnamese Regulars, decisively defeating same in a game-changing exercise in mobility not seen since Hitler’s panzers had steamrollered Poland in 1939.

A point worthy of remark here is the freshness of American troops, most of whom went into action for the first time and versus a tough and wily opponent. They came away with a victory, as opposed to similar initial efforts by American troops at such places as Bull Run, Kasserine and Osan with Task Force Smith.

Despite the fact there was still much to learn, the transition of peacetime development to wartime employment of airmobility seemed to be on its way.

The advent of the 11th Air Assault Division (Test) was an important step in the evolution of airmobility. But more than that, it was the attestation of a factor that was not only a prerequisite, but without which the efforts of folks such as Howze, Williams, Kinnard, Seneff and others would have come to naught. And then there was that ingredient that made this stew palatable, that everyone was basically on the same page—from Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to Secretary of the Army Elvis Stahr, to General Hamilton Howze to General Harry Kinnard and so on down the food chain. Minus this continuity, victory at Ia Drang would not have been possible.

* * * * *

Appendix[23]

Memorandum from Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara:

The Secretary of Defense

Washington

April 19, 1962

MEMORANDUM FOR THE SECRETARY OF THE ARMY

SUBJECT: Army Aviation (U)

This is in response to your two November 1, 1961, memoranda which discussed Army Aviation and presented the Army’s proposed procurement program.

These studies greatly enhanced my understanding of what the Army is seeking to achieve through its organic aviation. However, the quantitative procurement programs fall considerably short of providing, in the near future, modern aircraft to fill the stated requirements. While it appears to me that the Army can and should turn increasingly to aviation to improve its tactical mobility, your memoranda do not give a clear picture regarding either the optimum mix of aircraft types or the absolute total numbers that will be required.

Attached is an analysis of your studies made by my office. I would like your comments on this analysis with particular emphasis on the proposed increased buy of Army aircraft for 1964 and on the position that your predicted requirements in this area through 1970 are too low. These comments should be submitted by 15 May 1962.

Furthermore, I would like the army to completely re-examine its quantitative and qualitative requirements for aviation. This re-examination should consist of an extensive program of analyses, exercises and field tests to evaluate revolutionary new concepts of tactical mobility and to recommend action to give the Army the maximum attainable mobility in the combat area. It appears to me that air vehicles, operating in the environment of the ground soldier but freed from the restrictions imposed by the earth’s surface, may offer the opportunity to acquire quantum increases in mobility, provided technology, doctrine, and organization potentials can be fully exploited. I believe further that these mobility increases can be acquired without increased funding by reducing less effective surface transportation systems concurrently. The Army’s re-examination should therefore give special attention to the following:

(1) To what extent can aviation be substituted for conventional military surface systems of vehicles, roads, bridging, engineer troops, theater supply and hospital complexes, etc?

(2) Should newer concepts of VTOL or STOL fixed-wing-aircraft be substituted for helicopters, as a means of avoiding some of the high procurement and operating costs of helicopters?

(3) May we use heavy tactical lift. Combined with new techniques in air dropping and possibly better airlift construction and repair capability, to provide part of the logistic support for ground operations? There should be considered the possibility that Air Force lift may be available, after the first thirty or so days of a strategic lift, to augment Army tactical lift capabilities.

(4) What qualitative requirements can be defined for immediately developable V/STOL air vehicles optimized for such purposes as surveillance, target acquisition, weapons platforms, command posts, communications centers, or troop and cargo carriers of significantly heavier loads?

(5) What organizations and operational concepts are required to exploit the potential increases in mobility? Consideration should be given to completely airmobile infantry, anti-tank, reconnaissance, and artillery units.

(6) What other concepts and ideas, as well as major limitations, bear on this subject? We should seriously consider fresh, new concepts, and give unorthodox ideas a hearing.

The results of the study should be presented in terms of cost-effectiveness and transport-effectiveness factors. The study should involve the full use of field tests and exercises to test new concepts of mobility.

In addition, the use of operations analysts in planning, observing, recording data, and analyzing results for the field test program appears to me to be essential to the effective accomplishment of the entire re-examination.

As a first step in your re-examination of Army aviation requirements, I would like by 15 May 1962 an outline of how you plan to conduct the re-examination program. The re-examination should be completed and your recommendations submitted by 1 September 1962.

/s/ Robert S. McNamara”

* * * * *

The Secretary of Defense

Washington

April 19, 1962

MEMORANDUM FOR MR. STAHR:

I have not been satisfied with Army program submissions for tactical mobility. I do not believe the Army has fully explored the opportunities offered by aeronautical technology for making a revolutionary break with traditional surface mobility means. Air vehicles operating close to, but above, the ground appear to me to offer the possibility of a quantum increase in effectiveness. I think that every possibility in this area should be exploited.

We have found that air transportation is cheaper than rail or ship transportation even in peacetime. The urgency of war time operations makes air transportation even more important. By exploiting aeronautical potential, we should be able to achieve a major increase in effectiveness while spending on airmobility systems no more than we have been spending on spheres oriented for ground transportation.

I therefore believe that the Army’s re-examination of its aviation requirements should be a bold “new look” at land warfare mobility. It should be conducted in an atmosphere divorced from traditional viewpoints and past policies. The only objective the actual task force should be given is that of acquiring the maximum attainable mobility within alternative funding levels and technology. This necessitates a readiness to substitute airmobility systems for transitional ground systems wherever analysis shows the substitution to improve our capabilities or effectiveness. It also requires that bold, new ideas which the task force may recommend be protected from veto or dilution by conservative staff review.

In order to ensure the success of the re-examination I am requesting in my official memorandum, I urge you to give its implementation your close personal attention. More specifically, I suggest that you establish a managing group of selected individuals to direct the review and keep you advised of its progress. If you choose to appoint such a committee, I suggest the following individuals be considered as appropriate for service thereon: Lt. Gen. Hamilton H. Howze, Brig. Gen. Delk M. Oden, Brig. Gen. Walter B. Richardson, Col. Robert R. Williams, Col. John Norton, Col. A.J. Rankin, Mr. Frank A. Parker, Dr. Edwin W. Paxson and Mr. Edward H. Heinemann.

Existing Army activities such as Fort Rucker, STAG (Strategic and Tactics Analysis Group, Washington, D.C.), and C.D.E.C. (Combat Operations Development Experimental Center, Ft. Ord), and, C.O.R.G. (Combat Operations Research Group, Ft. Monroe), combined with the troops units and military study headquarters of CONARC, and in cooperation with Air Force troop carrier elements, appear to provide the required capabilities to conduct the analyses, field tests and exercises, provided their efforts are properly directed.

The studies already made by the Army of airmobile divisions and their subordinate airmobile units, of airmobile reconnaissance regiments, and of aerial artillery indicate the type of doctrinal concepts which could be evolved, although there has been no action to carry these concepts into effect. Parallel studies are also needed to provide air vehicles of improved capabilities and to eliminate ground-surface equipment and forces whose duplicate but less effective capabilities can no longer be justified economically. Improved V/STOL air vehicles, and as short range prime movers of heavy loads up to 40 or 50 tons.

I shall be disappointed if the Army’s re-examination merely produces logistics-oriented recommendations to procure more of the same, rather than a plan for implementing fresh and perhaps unorthodox concepts which will give us a significant increase in mobility.

/s/ Robert S. McNamara

Endnotes

[1] See page 12, “The 1962 Howze Board and Army Combat Developments,” by J.A. Stockfisch.

[2] See page 110, Chapter 5, “The Dynamics of Insurgency,” The Army Gets an Air Force, by Frederic A. Bergerson.

[3] See pages 99 and 100, Frederic A. Bergerson.

[4] To read both memorandums by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, see pages 39-42, “The Howze Board and Army Combat Developments,” by J.A. Stockfisch. Or, the reader may shortcut his or her search time by referring to the Appendix at the conclusion of this article.

[5] See page 15, J.A. Stockfisch.

[6] See page 237, 19, “The Howze Board,” A Cavalryman’s Story, by Hamilton H. Howze.

[7] See paragraph 4, page 1, “Memorandum for Mr. Stahr,” April 19, 1962.

[8] See page 21, Chapter 1, “The Growth of the Airmobile Concept, “ Vietnam Studies: Airmobility 1961-1971, by Lieutenant General John J. Tolson.

[9] See page 239, Hamilton H. Howze.

[10] See page 21, Lieutenant General John J. Tolson.

[11] See page 239, Hamilton H. Howze.

[12] See page 240, Hamilton H. Howze.

[13] See page 240, Hamilton H. Howze.

[14] General Kinnard was among those of the 101st Airborne Division who were encircled by General Baron Hasso von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army at Bastogne. He is popularly known to have urged General Anthony McAuliffe to respond to German entreaties for surrender with the most eloquent yet steadfast rejection of “Nuts!” See page 193, Part Three, 2, “Nuts!” Battle: The Story of the Bulge, by John Toland.

[15] See page 551, U.S. Army in World War II, Special Studies: “30 August: JAPAN—Occupation of Japan in force is begun by U.S. forces, 11th AB Dn is flown to Atsugi Airfield and 4th Marines, 6th Mar Div lands at Yokosuka Naval Base.”

[16] The “Rakkasans” were attached to the 11th Airborne Division in World War II, and, were the first Allied troops to set foot in Japan on August 30, 1945.

[17] According to Major Thomas I. McMurray and Major Larry E. Scoggins in the “History of the 227th for Year of 1965,” on February 11, 1963, the 31st Transportation Company (Light Helicopter) was re-designated and activated as Company B, 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion, and brought to the battalion its twenty-two CH-34 helicopters.” See page 2, McMurray and Scoggins. “On February 15, 1963, Company A, 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion was activated as the second of the battalion’s units. Company A was designated the aerial weapons armed escort company: Their UH-1Bs and armaments systems arriving in late April 1963.” See page 2, McMurray and Scoggins.

[18] The 10th Air Transport Brigade was not organic to the 11th AAD; rather, a unit of logistics support.

[19] See page 20, Forward Arming and Refueling Points for Mechanized Infantry and Armor Units, Chapter 2, “Review of Literature,” by Captain Jerrold M. Reeves, Jr., U.S.A. “The Vietnam War and its heavy reliance on helicopters led to the F.A.R.E. (Forward Area Refueling Equipment) study and caused the research and development of Forward Area Refueling Equipment. The F.A.R.E. not only provided the equipment for the Forward Area Refueling Point for helicopters, but also for ground equipment.”

“The culmination for the original plan of action was the development of the Forward Arming and Refueling Point Doctrine explained in FM 1-104, Forward Arming and Refueling Points, published in 1985.” See page 3, Captain Jerrold M. Reeves, Jr., U.S.A.

[20] The use of rocket-firing UH-1s in support of air assault units at landing zones was much like the Luftwaffe’s employment of the Junkers Ju-87 dive bomber to support panzer units at the point of the Wehrmacht’s armored thrusts.

[21] General Kinnard’s affirmation, then, coincides with the following practitioners of regular and irregular warfare: “When the situation is serious, the guerrillas must move with the fluidity of water and the ease of blowing wind. Their tactics must deceive, tempt and confuse the enemy. They must lead the enemy to believe that they will attack him from the east and north, and they must then strike him from the west and south. Guerrilla initiative is expressed in dispersion, concentration and the alert shifting of forces.” See pages 103 and 104, On Guerrilla Warfare, by Mao Tse-tung, translated by Brigadier Samuel B. Griffith, U.S.M.C., (Ret.). And . . .

. . . “Therefore, with the development of our forces, guerrilla warfare changed into a mobile warfare—a form of mobile warfare still strongly marked by guerrilla warfare—which would afterwards become the essential form of operations on the main front, the northern front. In this process of development of guerrilla warfare and of accentuation of the mobile warfare, our people’s army consistently grew and passed from the stage of combats involving a section or company, to fairly large-scale campaigns bringing into action several divisions.” See page 24, III. “The Fundamental Problems of Our War of Liberation,” People’s War, People’s Army, by Vo Nguyen Giap.

[22] See page 16, Lieutenant General Harold G. Moore, (Ret.) and Joseph L. Galloway. We Were Soldiers once . . . And Young.

[23} See pages 39-42, J.A. Stockfisch.

Bibliography

Adamczyk, Richard D. and MacGregor, Morris J., editors, United States Army in World War II, Reader’s Guide, CMH Pub 11-9, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1992.

Bergerson, Frederic A., The Army Gets an Air Force: Tactics of Insurgent Bureaucratic Politics, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, 1980.

Carland, John M., “How We Get There: Air Assault and the Emergence of the 1st Air Cavalry Division (Airmobile), 1950-1965,” The Land Warfare Papers, No. 42, The Institute of Land Warfare, Association of the United States Army, Arlington, Virginia, May 2003.

Graves, Major Thomas C., United States Army, Transforming the Force: The 11th Air Assault Division (Test) from 1963-1965, School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 1999.

Howze, Hamilton H., A Cavalryman’s Story: Memoirs of a Twentieth-Century General, Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington and London, 1996.

Mao Tse-tung, On Guerrilla Warfare, Praeger Publishers, Inc., New York, NY., 1961. Translated and Introduction by Brigadier General Samuel B Griffith, U.S.M.C., (Ret.).

McMurray, Major Thomas J. and Scoggins, Major Lary E., “Company A, 227th Helicopter Battalion, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), from History of the 227th Aviation Battalion, July 1, 1965-31 December 1965. a227ahb.org/History227th1965.html

Moore, Lieutenant General Harold G. and Galloway, Joseph L., We Were Soldiers Once . . . And Young: Ia Drang—the Battle That Changed the War in Vietnam, The Random House Publishing Group, New York, 1992.

Olinger, Mark A., “Conceptual Underpinnings of the Air Assault Concept: The Hogaboom, Rogers and Howze Boards,” The Land Warfare Papers, No. 60W, The Institute of Land Warfare, Association of the United States Army, Arlington, Virginia, December 2006.

Reeves, Captain Jerrold, Forward Arming and Refueling Points for Mechanized Infantry and Armor Units, AD-A272 826, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 1993.

Stockfisch, J.A., “The 1962 Howze Board and Army Combat Developments,” RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California, 1994.

“The Airmobile Division,” D.A. Pam 360-216, Headquarters, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 30 November 1965.

Toland, John, Bulge: The Story of the Bulge, Random House, Inc., New York, 1959.

Tolson, Lieutenant General John J., Vietnam Studies: Airmobility 1961-1971, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1989.

Vo Nguyen Giap, People’s War, People’s Army: The Viet Cong Insurrection Manual for Underdeveloped Countries, Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., New York, NY., 1962.

Weber, Colonel William (Ret.), “Unit History of the 187th,” www.thedropzone.org/units/187history.html