Looking Back, November 2025

By Mark Albertson

Operation: DESERT SHIELD

* * * * *

The single biggest maneuver factor on the battlefield was the Apache. If there was one leverage device that we used it was the Army general support aviation battalion. In my judgment, for the number of soldiers involved, and the price involved, the biggest leverage we got out of the very few numbers of helicopters, the tiny number of helicopters, that we devoted to support logistics, and command and control in general: the Signal battalion commander, the Maneuver Brigade commanders, the DISCOM commander, and the Division G3. Had COL James King (DISCOM Commander) not had Army Aviation UH-60s, UH-1s and Chinooks, there would have been a far different outcome. Many of us will never know the full story on that one. It made the difference of getting POL to the right spot because we could move the key logistics around the battlefield.

Who won the battle? Certainly, the artillery and the Apache. It will be hard to remember that eleven years from now, when you are in charge of force development working 20 hours a day. The artillery and the Apache are the hammers that make the endgame work.[1]

* * * * *

Economics of War

Colonel Tackaberry’s observation on the success of airmobility over Saddam’s host during Operation: DESERT STORM must conform to the preparatory process. For victory is not possible without same. And to understand that victory, we must return to that series of events that led up to STORM.

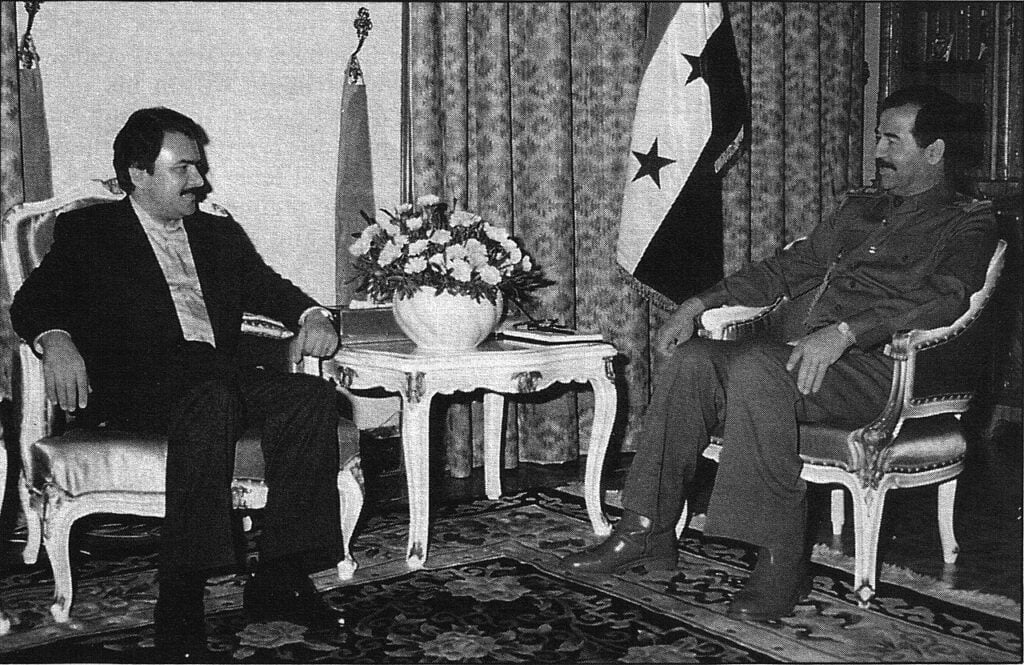

Saddam marched into Kuwait, August 1990, and triggered the massive military response to evict him from Kuwait, known as Operations: DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM. Shown with Saddam in this 1987 photo is Massoud Rajavi, leader of the Iranian People’s Mujahidin.

August 1, 1990, Saddam Hussein sent his army crashing into Kuwait. One week later, he had annexed same.[2] Yet Efraim Karsh provides the rationale for Saddam’s actions:

“Though the Iraqi regime went out of its way to portray the end of the war as a shining victory (that is, the Iran-Iraq War), the truth was that Iraq, no less than Iran, emerged from the eight-year conflict a crippled nation. At least 200,000 Iraqis had lost their lives, while about 400,000 had been wounded and some 70,000 taken prisoner; an exorbitant price for a nation of 17 million people. In 1980 Iraq could boast of a $35 billion foreign currency reserve; eight years later it had accumulated a foreign debt of some $80 billion—roughly twice the size of its Gross National Product. This debt was extremely onerous, since repayment arrears and the consequent reluctance of foreign companies and governments to extend further credits meant that the reconstruction of Iraq from the destruction wrought by the war would have to be shelved.

“Economic estimates put the cost of reconstruction at $230 billion. . . As things were a year after the termination of hostilities, Iraq’s oil revenues of $13 billion did not suffice even to cover ongoing expenditures: With civilian imports approximating to $12 billion ($3 billion for foodstuffs), military imports exceeding $5 billion, debt payments totaling some $5 billion; and, transfers by foreign workers topping $1 billion, the regime needed an extra $10 billion per annum to balance its current deficit, before it could even think of reconstruction; and this without taking into account the substantial domestic economic costs, such as the $2.5-$7.9 billion defense expenditure.”[3]

The harsh economic realities unfolding underscored the political corner Saddam had painted himself into. He needed cash and, in one quick hurry. In February 1990, in Amman, Jordan, Saddam petitioned King Hussein and President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt to notify the Gulf States that Iraq wanted a postponement on the loans by its “principals” during the war with Iran. And in addition, Baghdad wanted another $30 billion to boot.

Bottom line was that Iraq was over its head with $80 billion in red ink. Kuwait chose not to overlook $65 billion in economic assistance to Iraq in its war against its Persian neighbor. Baghdad countered that Iraq’s invasion of Iran was in Kuwait’s and Saudi Arabia’s benefit, since Saddam was carrying the Arab standard against the detested Shia Fundamentalist regime in Tehran. This, in addition to Iraq’s complaints that Kuwait was reaping undeserved oil profits from the Rumaila oil field, located as it was in territory under dispute by both Iraq and Kuwait. Baghdad, too, was hardly happy with the price of oil being depressed owing to the oil glut, blaming Kuwait for overproduction.[4]

“To pay off his country’s debts, Saddam Hussein needed oil prices to remain in the range of $25 a barrel (at the height of the Iran-Iraq War, prices had reached as high as $35 a barrel). He watched in despair as the international price slumped to $14 by July 1990. The Gulf, at peace once again, was now able to export all the oil the world needed. To make matters worse, some Gulf States were producing well beyond their OPEC quotas. Kuwait was one of the worst offenders. Kuwait had its own reasons for breaking ranks with OPEC over production quotas. Earlier in the 1980s, the Kuwaiti government had diversified its economy by investing in Western refineries and opening thousands of gasoline stations across Europe under the new brand name ‘Q-8,’ a homonym for ‘Kuwait.’ Kuwait’s crude oil exports increasingly went to its own facilities in the West. The more crude oil the Kuwaitis sold to their refineries, the higher their profits in Europe. These refining and marketing outlets generated higher profit margins than the export of crude and insulated Kuwait from variations in the price of crude oil. Kuwait was more interested in generating maximum output than seeking the highest price per barrel by hewing to OPEC’s guidelines.”[5]

But what does the above economic explanation have to do with Army Aviation? Simple, war is economics, as stated by none other than Adolf Hitler. Economic primacy is the major factor for the preservation of the modern American military. Paramount, if you will, of the preservation of American interests; which underscores the striving of fashioning an American military able to respond at a moment’s notice. Same has been reinforced on the pages of Army Aviation magazine, the publisher of this work. Yet . . .

“. . . As a strategic force, the Army must be prepared for instantaneous transition from peace to war. Our Army is trained and ready to make that transition should we ever be called upon to do so.”[6]

That “instantaneous transition” as alluded to by General Vuono has already been showcased with the invasion of Grenada. What will transpire in the liberation of Kuwait would provide a window, though, into Army Aviation’s role to be played in the AirLand battle concept. What far-sighted individuals such as Generals William DePuy and Donn Starry were attempting to forge in the wake of the calamitous result of Vietnam, came to fruition during Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

* * * * *

From Staunch to Storm

The preparatory phase of Desert Shield/Storm was the Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988. This conflict was an overt threat to Western energy interests, since more than fifty percent of the globe’s marketable and tradeable crude flowed from the area in contention The basic preference of the West in this conflict can be seen within the analysis of Anthony Cordesman in 1987:

“The West will not benefit from U.S. efforts directly supporting Iraq with weapons or other major assistance. This is a role that France and other European nations can perform. U.S. support of Iraq should be indirect, and linked to efforts to open lines of communication to Iran and to strengthen the southern Gulf States. In practice, this means using every political means to limit arms shipments to Iran, providing quiet intelligence support and providing political support for every serious peace initiative.

“The U.S. will, however, need to revitalize and sustain ‘Operation: STAUNCH,’ the U.S. effort to halt the flow of arms to Iran that began in 1983. It will need to continue to provide Iraq with agricultural credits, and be ready to support emergency aid by the EXIN (Export- Import) Bank and collective action by the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and World Bank. The U.S. should continue to share intelligence with Iraq of a kind it has provided since mid-1984 and to make every effort to reduce the risk of a successful Iranian offensive or surprise attack.

“In contrast, Europe needs to halt its arms shipments to Iran as much as possible and to concentrate on building up economic ties. It needs to be ready to extend and renegotiate loans, and help ensure Iraq can keep fighting. France plays a particularly critical role. Its arms supplies to Iraq are vital not only to preventing an Iranian victory, but to reducing Iraqi dependence on the USSR.”[7]

But the Iran-Iraq War proved a decisive factor in the destabilization of the most strategic area of the globe. Saddam Hussein, seeking to position Iraq as the new major Arab power in lieu of Egypt, which no longer was, expected quick victory in severing the Iranian province Khuzestan, known to Arabs as “Arabistan,” which would most certainly solidify Saddam’s effort at domination of the Arab world, let alone, perhaps, OPEC. For 70 to 80 percent of Iran’s oil reserves are in Khuzestan. Not only would Saddam be able to improve his standing and political advantage among Arab councils, but would cause irreparable damage to the Shia standard bearer, Iran.

Both Iraq and Iran emerged from the resulting protracted conflict crippled. The Iraqis, as mentioned previously, incurred upwards of 200,000 dead and another 400,000 wounded, with an additional 70,000 taken prisoner. Heavy losses for a nation of only 17 million. But a proper understanding of the opponent the Iraqis were engaged with for eight years is called for:

The Shia Fundamentalist regime in Iran had purged some 12,000 officers from the hated Shah’s regime that had been recently toppled. The Khomeini government created its own militia, the Pasdaran or Revolutionary Guard, a political military formation organized to act as a prophylactic to potential counterrevolution. Hence the aforementioned purge.[8]

On March 20, 1982, another military formation was formed in Iran: Basij e-Mustazafin or Mobilization of the Deprived, featured the mobilization of the young, those ages 12-18, organized into what were literally, in many instances, suicide squads.

Many of these recruits came “mainly from rural areas or from the most devout Shi’ite families, these poorly trained and ill-equipped youths, some as young as 12, were little more than cannon fodder or human minesweepers sent in advance of Iran’s other military forces to clear fields, desert scrubland and marshes. With their red and yellow headbands proclaiming Allah’s or Khomeini’s greatness, a piece of white cloth pinned to their uniforms as a symbol of a shroud, each one carrying his death with him, and a plastic key around their necks, issued personally by Khomeini as a symbol of their assured entry into paradise upon martyrdom, they charged towards Iraqi positions in total disregard of the danger to their lives, and to the shocked disbelief of their enemies.

“They came on in their hundreds, often walking straight across the minefields, triggering them with their feet as they are supposed to do. . . “ See page 62, “Iran’s Boy Soldiers,” The Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988, by Efraim Karsh.[9]

Such an opponent was pulling out all the stops to throw out the invader. And, was emblematic of the brutality of this conflict. A conflict which, together with the rise of the Shia fundamentalist regime in Tehran, would help to harden the lines of division between Shias and Sunnis and lend to what will become the faceoff between the Shia standard bearer Iran versus the Wahhabi agenda in Riyadh.

The year following the end of the Iran-Iraq War, the Soviets would evacuate Afghanistan, presaging the decline and collapse of not only the Soviet Union but also its vassal states in Eastern and Central Europe. The bipolar balance of power that had replaced the end of European domination of global affairs as of 1945, had given way to a unipolar world as the United States became the sole superpower. Yet the peace dividend that many expected has proven to be an illusion, one typical of the human condition. For China was coming on as a competitive power; as was India, Japan was still in the game. The European Union was trying to find itself in an uncertain New World Order, as was a struggling Russia.

Yet the Soviet incursion into Afghanistan and the ensuing Carter Administration assistance of the Mujahideen, carried forward by the Reagan Administration, opened a new conflict, that of the Jihadis. If they could throw an infidel power out of Afghanistan, then what could they do in the Middle East, after centuries of tiresome Western meddling and incursions.

* * * * *

Shield to Storm

“At about 2 a.m. (Baghdad time) on August 2, 1990, three Iraqi Republican Guard divisions invaded Kuwait. One proceeded down a coast road to Kuwait City, a second seized the inland oil fields, and the third proceeded to the Saudi Arabian border. Kuwaiti A-4 aircraft and Chieftain tanks fought for three days until their fuel and ammunition were exhausted. The small Kuwaiti Navy also made a valiant showing, with the last two fast attack craft escaping while firing at pursuing Iraqi tanks.

“Iraqi forces quickly captured Kuwait City and the Emir’s palace, while the Kuwaiti ruler, Sheik Taber al-Ahmed al-Sabah, fled to Saudi Arabia and established a government-in-exile. On August 3rd, the remainder of Kuwait was captured and by the 4th, Iraqi forces were massed along the Kuwaiti-Saudi border for a possible invasion of Saudi Arabia. If Iraq occupied Saudi Arabia, it would not only establish itself as the secular leader of the Arab world, but would also control forty-five percent of the world’s oil.”[10]

If Saddam had banked on the Soviet Union acting as a counterweight to the U.S. and NATO taking action to prevent his Anschluss with Kuwait, he most certainly had miscalculated. For the Soviet monolith was well along that progression of collapse; in addition to the unfolding demise of the Warsaw Pact, which demonstrated unequivocally what that “military alliance” really was, an empire.[11] Perhaps, too, the Iraqi dictator had thought that America had not recovered from the Vietnam debacle.

Following Saddam’s steamrollering of Kuwait, the United States and its NATO allies poured military personnel and equipment into Saudi Arabia. But due to the efforts of James Baker, forces other than that of the United States and NATO formed a broad-based coalition.[12]

“President George Bush, Sr., ordered American military forces to Saudi Arabia on August 7, 1990. By August 11, 13 Army helicopters had arrived in country. By the time the ground war began on 24 February 1991, XVIII Airborne Corps had 920 aircraft in Saudi Arabia, VII Corps had deployed 808, and Echelon Above Corps (EAC) and Army Special Forces had 160 for a theater total of 1,888 Army aircraft. During the period of August 1990 through March 1991, 2,010 Army aircraft flew 182,960 hours as part of the Army team. Ten aviation brigades directly participated in combat operations and other aviation forces provided essential combat support and combat services support to the theater.”[13]

The AH-1G Huey Cobra was Army Aviation’s first true attack helicopter. Coming out of Vietnam, it will be the Army’s attack helicopter until the advent of the AH-64 Apache. The Cobra still performed in the Operation: DESERT STORM.

Yet according to Major General Donald R. Williamson, “Operation Desert Shield found the U.S. Army Aviation Systems Command (AVSCOM) operating on an underfunded spares budget supporting an over-programmed flying hour program.”[14] Production, though, was expanded and accelerated. Additional stocks, transport of supplies, maintenance of aircraft and equipment to accommodate not only a noticeable increase in flying time, but the expected wear and tear with operations in a challenging environment.

“This stepped up activity included over $300 million in new procurement, 2,000 spares programs accelerated, and 600 depot programs surged. This magnified response by both AVSCOM and industry was only hampered by lead times for raw materials and in some instances, forgings and castings.”[15]

The AH-64 Apache became and still is the Army’s premier attack helicopter, having assumed that mantle from the AH-1 Cobra.

In face of the wear and tear in the desert, Colonel Thomas W. Garrett, Commander, Aviation Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, explained some of the conditions faced even in the assembly areas:

“Even at semi improved areas, the sand and dust quickly began to exact a heavy maintenance toll. Blade erosion, engine problems, and avionics trouble were the most worrisome. Our newest aircraft have faired the best. AH-64, OH-58D and newer UH-60s (in order) have held up well. Dust control has become a major concern. Low cost, widely available, and easily applied dust control measures are urgently needed.

UH-60 Black Hawk replaced the aging UH-1 Huey as the utility helicopter for the AirLand Battle Concept.

“Desert night flying has proved to be the toughest of challenges. We are adjusting tactics and techniques to allow us to continue to accomplish our mission, but we had to learn the hard way. Heads up displays for goggles, continued goggle refinement in the areas of acuity and field-of-view, forward looking radar altimeters, and aural altitude warning would greatly enhance our ability to conduct safer night desert operations. A system like the USAF’s ‘Harvest Bare’ needs to be reviewed by Army Aviation. Crew rest, especially for night crews, is next to impossible. A portable base like ‘Harvest Bare’ would be a present from Heaven for many an aviation brigade here in Saudi Arabia.

“Accurate navigation in a featureless desert, day or night, has been challenging. Old maps coupled with shifting dunes and lake beds make even Doppler update waypoints suspect (if you’re lucky enough to have Doppler), allowing for drift errors to build. We must press on with GPS hand-held commercial LORANS, which have been a life saver.”[16]

Perhaps it was Major General Rudolph Ostovich, III, then Chief, Aviation Branch, Commanding General and Commandant, U.S. Army Aviation Logistics School, who observed that with the coming end of the Cold War, the Army was to be reduced, from 28 divisions to 22, resulting, then, in fewer forward deployed forces. “The forces stationed in CONUS will provide both reinforcing combat power for forward deployed forces as well as a contingency capability to respond quickly and decisively in support of our national security interests. Our contingency forces will include heavy, light, and special operations units and there will be a premium on deployable weapons systems that are both versatile and lethal. Army Aviation stands at the forefront of these initiatives. Pound for pound, we are the most deployable, versatile, and lethal of today’s Army forces.”[17]

He continues his analysis, thus: “In response to the challenges in our future, CG, TRADOC initiated Studies and General Officer workshops to redefine our doctrine and identify alternative balance force structures. Through these concept development vehicles, we examined an emerging doctrine tagged AirLand Battle-Future. The concept is founded on a precept that future battlefields will be nonlinear. By this, we mean that no longer will we have the forces to line up hub to hub or rotor to rotor and stretch from coast to coast. We accept the fact that there may be large gaps between formations. We will no longer concentrate our effort to seize and hold terrain.”[18] Rather we will focus our destructive power on the enemy force. We will employ state-of-the art intelligence gathering sensors and air cavalry to find and fix the enemy. Attack helicopters, Close Air Support/Battlefield Air Interdiction, and long-range artillery fires will shape the battlefield for decisive destruction of the enemy through high speed and dynamic maneuver. Depth and rapid concentration of overwhelming destructive power are the essence of aviation’s contribution to our future as a fighting doctrine.”[19]

* * * * *

Endnotes

[1] See pages 28 and 29, “24th Aviation Brigade in Desert Storm,” Part I, Army Aviation, June 30, 1991, by Colonel Burt S. Tackaberry.

[2] See page 152, Chapter 8, “Bush, Clinton, and the Triumph of Wilsonianism,” The Folly of Empire, by John B. Judis.

[3] See page 89, “A Costly Exercise in Futility,” The Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988, by Efraim Karsh.

[4] See page 17, Part 1, “The Prelude,” Military Lessons of the Gulf War, by Bruce W. Watson; Bruce George, Labor MP; Peter Tsouras and B.L. Cyr.

[5] See page 442, Chapter 14, “After the Cold War,” The Arabs, A History, by Eugene Rogan.

[6] See page 4, “Training and Readiness,” Army Aviation, May 1, 1989, by General Carl E. Vuono.

[7] See page 158, Chapter Eight, “The Impact on Western Policy,” The Iran-Iraq War and Western Security, 1984-87, by Anthony H. Cordesman.

[8] In Egypt, beginning in 2011, the uprising against Hosni Mubarak, eventually resulted in the Muslim Brotherhood attaining power, though only briefly. The Egyptian armed forces reclaimed power, unseating the Brotherhood. Understood among the Egyptian Officer Class was the brutal purging of the Shah’s officer class by the Shia fundamentalists in Iran. History, here, In Egypt, was not to be repeated.

[9] Throughout history, nations or empires attempting to deal with manpower shortages, or generate manpower superiority in the face of material disadvantages or seek to galvanize patriotism or, seek to create a more disciplined environment, utilized aspects of the above to create a military advantage. For instance, Stalin’s infamous Order No. 227, July 28, 1942, “Not a Step Back,” which was to stiffen the spine of Soviet soldiery. No commander had the right to retreat without specifically being ordered to do so.

Known as penal battalions or Shtrafbats, such troops were cannon fodder, as they ran through minefields or assaulted enemy positions prior to regular line troops. Soldiers consigned to such units were considered to have exhibited the less than required intestinal fortitude against the “fascist invader.”

Blocking detachments, formations of NKVD (forerunner of the KGB) lay in wait behind the lines to enforce the compliance of those who retreated. Though it was possible to be reassigned to a regular unit when a candidate had demonstrated that he was ready for such a hoped for transfer.

Upwards of 442,700 Soviet soldiers served in the penal battalions. This, in addition to the fact, that Stalin had some 158,000 shot for cowardice or incompetence. This included 248 generals and admirals, so Stalin did have a more “liberal” view on maintaining discipline. Indeed, Stalin is reputed to have replied, to a question as to the Shtrafbats, that “. . . it took a brave man to be a coward in the Red Army.”

Germany, too, 1944-1945, resorted to young teens when hard up for men. February 1945, Hitler ordered the induction of 6,000 boys, ages 15 to 16, to “beef up the rear defense line.” See page 236, Chapter 9, “The Final Sacrifice,” Hitler’s Children, by Gerhard Rempel. There was also the Werewolves, German youth organized to conduct behind the lines disruption and sabotage, as well as carryout assassinations of enemy soldiers, agents and German “collaborators.” Indeed, on March 25, 1945, the American-installed mayor of Aachen, Franz Oppenhoff, was liquidated by a local Werewolf commando squad. Such squads of Hitler Youth were active to well into 1946. See pages 182-184, Chapter 10, “The End of the Hitler Youth,” Hitler Youth, by Brenda Ralph Lewis.

[10] See page 15, Part I: “The Prelude,” 1: “The Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait,” Military Lessons of the Gulf War, by Bruce W. Watson; Bruce George, MP; Peter Tsouras and B.L. Cyr.

[11] Adolf Hitler returned home, to Austria, March 12, 1938; to which he even brought a large circle of friends for the happy occasion, that being the success of the German Army. Known as Operation: OTTO, the absorption of Austria into the German Reich, is known to history as the Anschluss or annexation, which was in violation of the Versailles Treaty, Section VI, Article 80. To Saddam and other Iraqis, Kuwait was known as the 19th province.

[12] Such contributors as:

Afghanistan: 300 Mujahideen troops (under Joint Forces Command).

Bahrain: 3,500 troops (under Joint Forces Command).

Bangladesh: 2,500 troops (under CENTCOM administrative command).

Czechoslovakia: 350 men, chemical troops and 170 to Saudi Arabia (under administrative command).

Egypt: 40,000 troops, 400 tanks, 600 APCs and 300 artillery pieces.

Kuwait: 7,000 troops (under administrative command).

Morocco: 2,000 troops (under CENTCOM administrative command).

Niger: 400 troops (under CENTCOM administrative command).

Oman: 2,500 troops and 24 tanks (under Joint Forces Command).

Pakistan: 10,000 troops (under Joint Forces Command).

Qatar: 4,000 troops (under Joint Forces Command).

Saudi Arabia: 95,000 troops, 550 tanks (under Joint Forces Command).

Senegal: 500 troops (under ENTCOM administrative command).

Syria: 20,000 troops (under Joint Forces Command).

United Arab Emirates: 4,000 troops (under Joint Forces Command). See page 240, E., Ground Forces, Military Lessons of the Gulf War, by Bruce W. Watson; Bruce George, MP; Peter Tsouras and B.L. Cyr.

[13] See pages 44, 45 and 54, by Major General Robert S. Frix and Major Ronald A. Carter, “Third Army View of Desert Shield/Storm,” Army Aviation, Vol. 52, No. 12, December 31, 2003.

[14] See page 14, “AVSCOM: A Desert Shield Overview,” Army Aviation, Vol. 40, Nos. 3 & 4, March-April 1991, by Major General Donald R. Williamson.

[15] See page 14, Major General Donald R. Williamson.

[16] See page 23, “DESERT SHIELD: The Challenges,” Army Aviation, Vol. 39, No. 11, November 30, 1990, by Colonel Thomas W. Garrett.

[17] See page 12, “Contingency Warfare: Our Strong Suit,” Army Aviation, Vol. 39, No. 10, October 31, 1990, by Major General Rudolph Ostovich, III.

[18] Major General Ostovich, with his wonderfully orchestrated effort of how America must prosecute its military requirements in the post-Soviet era, is also fortifying a reality that has existed since November 25-26, 1950, when 300,000 Chinese troops entered the Korean War, forcing a ceasefire on July 27, 1953, thereby insuring the survival of the North Korean regime; but which also put the finishing touches on Levee en Masse. A period when Army doctrine saw to the destruction of the enemy forces so as to bring the opposing power to the conference table for the declaration of terms. Such was highly successful in 1865, 1918 and 1945.

Of course, beginning with the Bomb, Levee en Masse, conscripting entire populations and economies for war came to a screeching halt, especially in the West, where many populations in the developed world most likely would not show up (just after 9/11 in the United States being an example) for a war. The Great War, 1914-1922; 1931-1945, is largely responsible for this after the horrible harvest of humanity, upwards of some 75,000,000 souls, mostly on the European continent.

General Ostovich notes the necessity of destroying the enemy force, in particular since American troops will most likely field the smaller team. The example here is Genghis Khan’s Mongol Army: Mobility was the key to success, of what was arguably the most victorious army in the history of Man. For upon the defeat of an opponent, his host was pursued and hounded until eradicated; in addition to a finishing stroke applied to the leader himself. Certainly saves the distribution of forces to occupy a territory for the purposes of policing it for cleaning out pockets of resistance.

[19] During Operation BARBAROSSA, Hitler’s overriding concern was the destruction of Stalin’s Red Army, in lieu of taking and holding territory. The Fuhrer understood Napoleon’s failure to hold Moscow in 1812. But this was the Soviet Union of 1941, not France of 1940. The mammoth size of the Soviet colossus helped the Soviet Army survive the Nazi onslaught, as did Russia’s most faithful allies, General Winter and General Mud. A grander analysis, though, is beyond the scope of this work; despite which the point as noted should be readily understood and well taken.

* * * * *

Bibliography

Cordesman, Anthony H., The Iran-Iraq War and Western Security, 1984-1987, Jane’s Publishing, Company, Ltd., London, 1987.

Friedman, Norman, Desert Victory: The War for Kuwait, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1991.

Fris, Major General Robert S. and Carter, Major Ronald A., “Third Army View of DESERT SHIELD/STORM,” Army Aviation, Vol. 52, No. 12, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Monroe, Ct., December 31, 2003.

Garrett, Colonel Thomas W., “DESERT SHIELD: The Challenges,” Army Aviation, Vol. 39, No. 11, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., November 30, 1990.

Judis, John B., The Folly of Empire, A Lisa Drew Book/Scribner, New York, NY., 2004.

Karsh, Efraim, The Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988, Essential Histories, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2002.

Lewis, Brenda Ralph, Hitler Youth: The Hitler Jugend in War and Peace, 1933-1945, MBI Publishing, Company, Osceola, Wisconsin, copyright Amber Books, Ltd., 2000.

Ostovich, Major General Rudolph, III, “Contingency Warfare: Our Strong Suit,” Army Aviation, Vol. 39, No. 10, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., October 31, 1990.

Rempel, Gerhard, Hitler’s Children: The Hitler Youth and the SS, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, 1989.

Rogan, Eugene, The Arabs: A History, Basic Books, New York, NY., 2009.

Tackaberry. Colonel Burt S., “Part I: 24th Aviation Brigade in DESERT STORM,” Army Aviation, Vol. 40. No. 6, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., June 30, 1991.

Vuono, General Carl E., “Training and Readiness: Challenges for Army Aviation,” Army Aviation, Vol. 38, No. 5, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., May 31, 1989.

Watson, Bruce W.; George, Bruce, MP; Tsouras, Peter and Cyr, B.L., Military Lessons of the Gulf War, Greenhill Books, Presidio Press, Novato, California, 1991.

Williamson, Major General Donald R., “AVSCOM: A Desert Shield Overview,” Army Aviation, Vol. 40, Nos 3 & 4, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., March-April 1991.