Looking Back, June 2025

By Mark Albertson

Rover Joe, Horsefly, Timothy and Pineapple

As with any other endeavor that is from the mind of man, there is that period of trial and error until that level of efficiency is hopefully attained. This was certainly the case with trying to reach a functioning system of joint forward air controllers so as to provide the ground forces with effective close air support. Following the campaign in North Africa and the 35-day Sicilian operation that resulted in the removal of Axis forces, it was not until the Italian campaign that greater efforts were made to improve the functionality and coordination between ground and air for CAS.

An issue for improving close air support was motivating the Army Air Forces towards a more avid interest in same. For after the war, as pointed out by historian Harry Cole, “’it is obvious that at the time of the Sicilian campaign much remained to be done in the improvement and coordination of techniques of air operations in close support of ground forces.’ Tactical air control inefficiencies largely stemmed from American air commanders’ reluctance to become involved in the joint planning effort, which was an apparent result of the Mediterranean Air Command’s intent to assert its recently acquired autonomy. The situation only began to improve after U.S. Fifth Army Commander General Mark W. Clark made an emphatic request for better air integration, and Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower issued a virtual directive for a more active tactical air support role from the ‘so-called Strategic Air Force.’”[1]

Cooperation between air and ground forces improved. This despite the fact that German resistance caused the Allied advance up the Boot to slow and even grind to a halt, going into the spring 1944.[2]

Improved cooperation between ground forces and air staffs resulted in a command and control procedure that was sophisticated enough to accommodate the lowliest of requirements. Missions to be requested for action the following day would be sent up the food-chain of command until it reached the Corps level. Here staff would coordinate CAS requests with Army level. Army and air staffs huddled for evening meetings. Missions would be scheduled, depending, of course, on the availability of aerial assets.

But then there was the fluid situation, an urgent request for support from the front that required immediate attention. This was the “call request.”

“Call requests for air support against rapidly developing targets originated with a radio call from the front-line requesting agency to the division. The division immediately passed the request up to the joint air-army control center at the army headquarters, while the corps and army commands monitored the net, offering tacit approval for the request with their silence. Final approval for the request came from the army and air force operations officers at the control center. ‘Approved’ missions were tasked to air units operating on alert status in the air operations directive. Call missions frequently achieved their goal of having aircraft on-station within ninety minutes of the initial request. While formalizing the air tasking process greatly contributed to the operational availability of CAS aircraft, the introduction of forward air controllers enabled tactical air ground integration.”[3]

The forward air controllers were a tactical improvement for the integration of air-ground cooperation. AKA “Rover Joes,” their function was to insure the success of pilots answering the call-request owing to the lack briefing prior to the mission. Yet Rover Joes proved useful for scheduled missions or call-requests.

The Rover Joes were devised by the XII Air Support Command. These were generally made up of an Army Air Forces officer (pilot) and a ground forces officer working from a concealed position at the front. Hill tops were sought because of the advantage offered for a more commanding view of the battle area. “Their radio equipment, behind the hill out of sight of enemy observers and protected from enemy fire, was operated by enlisted personnel who communicated by telephone to the observation post.[4] Ground units seeking the elimination of attacking enemy forces or those enemy strongpoints offering resistance to an offensive were primary targets of opportunity.

The process entailed the ground forces, when seeking air support for the elimination of an enemy target, radioed the Rover Joe unit. Clearance was required by air and ground officers at the ground-air control center. Once this was done, the Rover Joe radioed the fighter-bombers which were nearby so as to conduct their attack.

The Rover Joe controller, using maps and aerial photographs, briefed the flight leader as to the features of the terrain as well as having the artillery mark the target area with colored smoke. The fighter-bombers would then give the target a going over with strafing runs and or bombing. The Rover Joe unit would then record the results of the attack. Indeed, the whole process could take less than 15 minutes.[5]

Direct radio contact between Rover Joe units and supporting fighter-bombers improved close air support efforts for the ground forces. Regardless, though, it was still not the adequate solution that was needed. Being on the ground, many times Rover Joe controllers and observers could not find suitable positions for observation. Many times the view was restricted to only several hundred yards of front. Hardly a panoramic view. British criticism included that the Rover Joe system worked better within static situations as opposed to actions of a more fluid nature, which could result in the bombing or strafing of friendly troops. What was required, then, was an unrestricted view, one that offered a constant visual contact of enemy positions. This could only be done from the air. This led to the introduction of the “horsefly.”[6]

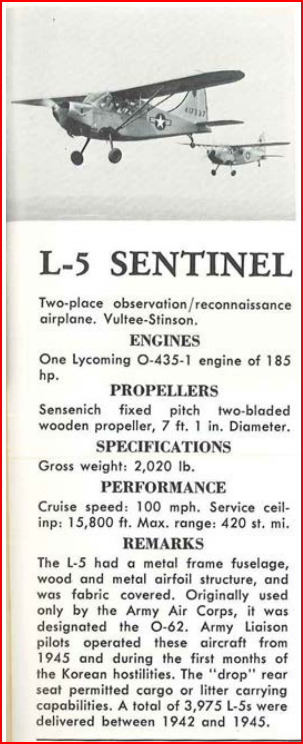

L-5 Sentinel Specifications

Horsefly planes were referred to as such in Army Air Force transmissions. Since they were needed close to the front, the horsefly operated off ground forces airstrips near the front lines. The Stinson L-5 was the plane and was usually flown by an AAF fighter-bomber pilot assigned on temporary duty and, was generally from the fighter-bomber squadron assigned for ground support operations. The observer was from the ground forces and from the unit to which the horsefly had been attached.

Horsefly aircraft were distinguished by stripes painted atop the wings, perhaps red or orange. Such would identify this particular liaison plane from any other along the same front.

Preparatory to each mission, horsefly crews were briefed. Maps and aerial photographs of the target in question were employed to ready the pilot and observer. Indeed, such briefings were the result of an aerial reconnaissance of the front conducted by the horsefly.

Once taking off, the horsefly rendezvoused with the fighter-bombers it was to direct behind friendly lines. Then it was on to the target.

Once at the target, the horsefly would direct the fighter-bombers by radio; and, if need be, mark the target with smoke grenades. At times, horsefly crews were only thirty feet from the ground when dropping smoke grenades so as to assure the destruction of the target.

“On 29 June [1944] an experiment was made using 1st Armored Division L-5s to direct fighter plane attacks. The controllers were air officers who flew in four L-5s, each painted a different color for identification (Horsefly Yellow, Horsefly Blue, etc.). The experiment was not considered a complete success, but it did prove the idea was practical.”[7]

The British were hardly keen on the horsefly principle, considering the ground observation principle more efficient despite its limitations. The Americans differed here as to the aircraft’s ability to offer a wider view of the battlefield. Americans thought, too, that the horsefly principle would prove more successful on a fluid battlefield. As to the vulnerability of the flivver plane, it was believed by Americans that the L-5 could operate at an altitude of 6,000 feet and five miles behind enemy lines. That is, of course, that air superiority had been established. And once into 1944, this was becoming and ever present reality.

Another attempt at establishing a functioning close air support technique was that of “Timothy.” This was first used in the Italian campaign on November 12, 1944, “when Desert Air Force Pilots provided close support for a British brigade offensive. An Eighth Army history states: ‘[It] took the form of a ‘Blitz’ in a limited area on either side of the brigade’s axis of advance, to a depth of about 1,000 yards, in front of a smoke bomb line. Three attacks had been prearranged (at 0730, 0830 and 0930) each consisting of 24 aircraft. Results were so good that the attacks were repeated. . . .’

“By the end of the day, the brigade had advanced 2,000 yards and taken 106 prisoners at a cost of 13 casualties. Timothy was undertaken again the next day with both British Spitfires and American P-47 Thunderbolts participating, and it continued to be used for the remainder of the campaign.

“Timothy’s essential prerequisite was that it had to be tied in with a ground offensive whose forces had to take immediate advantage of the air attack. The land formations had to furnish precise information on positions, targets and timing. It was also imperative that two safety factors be observed: (1) the local Rover must control the operation, ordering the smoke bomb line only after pilots had announced they were in the area, and then giving orders to attack and to cease; and, (2) pilots must be briefed not to attack unless both the smoke bomb line had been laid according to plan and Rover had expressly given his permission. This type of operation could degenerate into ‘area bombing’ rather than for an advance in a specific, heavily defended sector, but it did prove effective on a number of occasions.

“Another widely used technique, called ‘Pineapple,’ was designed to strike lucrative moving targets discovered by tactical aircraft on reconnaissance missions. Most often, the reconnaissance pilot radioed the army-air control center in the clear, indicating the target location, direction of movement, and composition. If the air force representative could accept the request for attack, the control center immediately passed it on to Pineapple-designated aircraft on alert, which at times were able to reach the target area within 15 minutes of receiving the order. The reconnaissance pilot would assist fighter-pilot pilots in locating the target. If the target was not clearly visible, the reconnaissance pilot might even lead the attacking flight to it. Occasionally, in addition to the control center, the reconnaissance pilot might contact a Rover for support. If the control center gave permission, Rover selected a rendezvous point from which the reconnaissance pilot picked up the fighter-bombers to lead them to the target. Since enemy ground or anti-aircraft fire could make an attack on the target too dangerous, the leader of the Pineapple flight could still the situation by using the code-word Nuts.[8]

Following the Allied success at Normandy, the horsefly continued to be used in France. This was particularly true with First and Third Armies. According to Ken Wakefield, “The Third Army employed Horsefly operations for the first time during its offensive in the Saar, two L-5s giving coverage from dusk to down. The technique was used with great success, the airborne controllers directing numerous fighter-bomber strikes against both pre-arranged and opportunity targets during the drive to the Rhine and beyond. The 9th Infantry Division also used its liaison aircraft to direct fighter-bomber attacks and found those against targets of opportunity, where there was no time to brief pilots, particularly rewarding. Approval of the method was also to be found in a report by VI Corps which stated that Horsefly was responsible for much effective bombing of Siegfried Line fortifications. In addition, vast amounts of enemy material was destroyed by air-directed close support in its drive to the Rhine and on into Bavaria and Austria. Nevertheless, Horsefly was not without its critics and there were those who favored control of fighter-bombers by similar high-performance aircraft; certainly, as the critics argued, Horsefly operations were feasible only where air superiority enabled slow, unarmed and unarmored aircraft to operate with relative immunity.”[9] Such criticism had dogged horsefly ever since it was introduced in Italy.

Of course, as with any other aspect found in war, horsefly was not without its human cost. Again, Wakefield: “On Christmas Eve (1944), Technical Sergeant Charles W. Leipersock, flying L-5 42-99605 on a Horsefly mission, with Major Randolph M. Jordan of the 10th Armored Division, failed to return to the squadron’s strip in Luxembourg. Sometime later it was learned that the L-5 had crashed near Ettelbruck, shot down in flames by flak. Sergeant Leipersock managed to bale out and was taken prisoner by a German tank crew, but nothing further is known of Major Jordan. Later at the end of April 1945, Charles Leipersock was released from captivity by the Third Army and was flown back in an L-5 from Landshut, Germany, for a memorable reunion with his squadron colleagues.”[10]

Data: Republic P-47 Thunderbolt

The razor-back P-47D, with its eight .50 caliber machine guns. At 17,500 full-load tons, the Thunderbolt was the heaviest single-engine fighter in World War II. Indeed, the P-47 was only 4,000 pounds less than the twin-engine Bristol Beaufighter.

The P-47 Thunderbolt was a fighter plane, bomber escort and utilized as a fighter-bomber for the interdiction role and close air support. The “Jug” was rugged yet speedy and with its eight .50 caliber machine guns packed a lethal punch. At seven and one-half tons, it was the heaviest single-engine fighter of World War II. And in its ground-support role, P-47s could take a punch. This writer knew a P-47 pilot who flew 85 missions in ground-support. His plane was replaced five times; but, all of his rides, shot up as they were, got him home.

| Power plant | One 2,535 hp Pratt & Whitney R-2800-59 Double Wasp Radial. |

|---|---|

| Wing span: | 40 feet, 9 inches. |

| Length: | 36 feet, 1 inch. |

| Height: | 14 feet, 2 inches. |

| Weight empty: | 10,700 pounds. |

| Weight loaded: | 17,500 pounds. |

| Crew: | 1 pilot. |

| Max speed: | 433 mph at 30,000 feet. |

| Service ceiling: | 42,000 feet. |

| Normal range: | 590 miles. |

| Armament: | Eight .50 caliber machine guns; up to 2,500 pounds of bombs or ten Rockets.[11] |

A diving P-47 Thunderbolt loosing missiles at a ground target.

According to data supplied by Republic Aviation Corporation, the P-47 during “World War II dropped 132,482 tons of bombs, expended over 135 million rounds of ammunition and some 59,567 rockets and several thousand gallons of napalm. 3,752 enemy aircraft were claimed to be destroyed in the air, and a further 3,752 on the ground. This effort required 1,934,000 flying hours and 204,504,000 gallons of fuel.

“Two-thirds of all P-47s produced eventually found their way to USAAF units in combat theaters, and losses of aircraft on operational missions were only 0.7 percent of those dispatched. From D-Day to V-E Day in Europe, the P-47 low level strikes accounted for 86,000 railway wagons, 9,000 locomotives, 6,000 armored vehicles and tanks, and 68,000 motor trucks. The total P-47 production consisted of 15,683 aircraft, some 31 Thunderbolt groups being in action in 1944.”[12]

Endnotes

[1] See page 28, Chapter 2, Literature Review, World War II, “Rebuilding the Joint Airborne Forward Air Controller Analyzing Joint Air Tasking Doctrine’s Ability to Facilitate Effective Air-Ground Integration,” by Major David Scott Chadsey, USAF, 2013.

[2] Fifth Army’s way to Rome was blocked for weeks owing to the German control of the commanding heights of Monte Cassino. “Monte Cassino—Monastery Hill, as it became known to the men of many nations who fought under its shadow for so many weeks—completely controlled both the valley that lay before it and also the Liri River to the northwest. Route 6 runs up to, then around the foot of the southern flank of Monastery Hill, having passed through the little town of Cassino which itself snuggles under the haunches of the 1,600 foot hill. From the summit of Mount Cassino, an observer could watch any movement in both the valleys, and by artillery and mortar fire seal off the vital artery to Rome, Route 6.” See pages 18 and 19, Chapter 2, “The Germans Come to Cassino,” The Battles for Cassino, by Brigadier General E.D. Smith.

[3] See page 30, Major David Scott Chadsey.

[4] See page 209, Chapter 5, “Allied Cooperation in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1945,” Case Studies in the Development of Close Air Support, edited by Benjamin Franklin Cooling.

[5] The British employed a like system to Rover Joe. Though when dispatching support aircraft it was generally six fighter-bombers as opposed to the American four aircraft. See page 209, Benjamin Franklin Cooling.

[6] See page 93, IV, “Couriers and Angels,” Jeeps in the Sky, by Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Ten Eyck.

[7] See page 144, Chapter III, “The War Years, North Africa, Sicily and Italy,” The Army Aviation Story, by Richard Tierney with Fred Montgomery.

[8] See pages 218 and 219, Benjamin Franklin Cooling.

[9] See page 118, Chapter Eighteen, “16th December 1944-25th January 1945: The Battle of the Bulge and War in the Rhineland,” The Fighting Grasshoppers, by Ken Wakefield.

[10] See page 123, Ken Wakefield.

[11] See page 141, “Republic, P-47 Thunderbolt,” Aircraft of World War II, by Kenneth Munson.

[12] See pages 14 and 16, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, Described, Part I, by Geoff Duval.

Bibliography

Cannon, Hardy D., Box Seat Over Hell, San Antonio, Texas, June 1985.

Chadsey, Major David Scott, USAF, “Rebuilding the Joint Airborne Forward Air Controller Analyzing Joint Air Tasking Doctrine’s Ability to Facilitate Effective Air-Ground Integration,” U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, December 13, 2013.

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin, editor, Case Studies in the Development of Close Air Support, Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force, Washington, D.C., 1990.

Duval, Geoff, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, Described, Part I, Kookaburra Technical Publications, Dandenong, Victoria, Australia, 1969.

Eyck, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Ten, Jeeps in the Sky, Commonwealth Books, New York, 1946.

Greenfield, Kent Roberts, Colonel of the Infantry, Army Ground Forces and the Air-Ground Battle Team Including Organic Light Aviation, Study No. 35, AD-A954 913, Historical Section, Army Ground Forces, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1948.

Love, Terry M., L-Birds: American Combat Liaison Aircraft of World War II, Flying Books International, New Brighton, Minnesota, 2001.

Munson, Kenneth, Aircraft of World War II, Ian Allen, Great Britain, 1962.

Raines, Edgar F., Eyes of Artillery: The Origins of Modern U.S. Army Aviation in World War II, CMH Pub 70-31-1, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 2000.

Smith, Brigadier General E.D. Smith, The Battles for Cassino, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1975.

Tierney, Richard with Montgomery, Fred, The Army Aviation Story, Colonial Press, Northport, Alabama, 1963.

Wakefield, Ken, The Fighting Grasshoppers: U.S. Liaison Aircraft Operations in Europe, 1942-1945, Mid Counties Publications, Leicester, England, 1990.