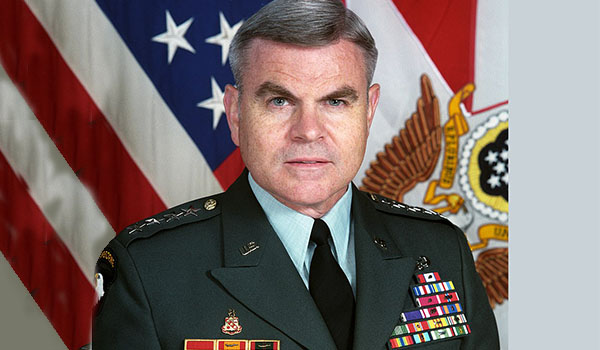

Guest Editorial, By General J.H. Binford Peay III, Commander-in-Chief, United States Central Command, MacDill Air Force Base, Florida. Edited by Mark Albertson.

* * * * *

General George S. Patton once declared that you should never attack where the enemy expects you to come. Attack weakness. Hold the enemy by the nose and kick him in the pants.[1]

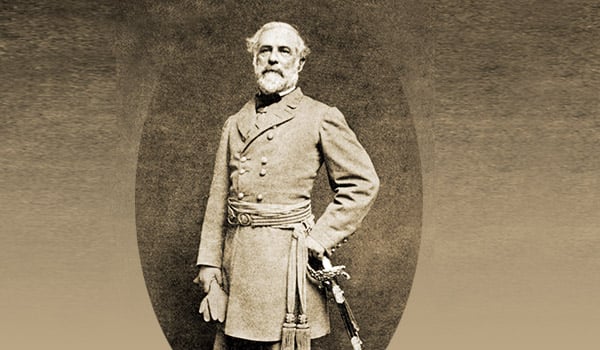

General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, engaged a Union Army superior in numbers, commanded by General Joseph Hooker. Lee audaciously divided his smaller army and with the use of the indirect approach, as alluded to by General Peay, defeated the Federals at the battle of Chancellorsville, May 1-6, 1863 / Wikipedia Commons/Heritage Auction Archives

In his own pithy way, Patton was recounting the much talked about coveted indirect approach in battle. Hannibal’s maneuver at Cannae, Napoleon’s triumph at Austerlitz. Lee’s surprise at Chancellorsville, MacArthur’s gamble at Inchon, and Schwarzkopf’s “hail Mary” offensive all reflected the Great Captain’s drive to gain military victory quickly, decisively, and at least cost by doing the unexpected. Advances in military technology during the last half century have raised this concept to new heights, accelerating changes in weaponry and doctrine that pose both opportunities and mindboggling challenges for the American military. Nowhere is this more evident than in the maturation of Army Aviation. We have seen it evolve from aerial observer for the artillery during World War II, air ambulance during the Korean War, and troop transporter in Vietnam to become a lethal weapon of maneuver and destruction during DESERT STORM. This transformation has not escaped the attention of the United States Central Command, where the capabilities of Army aviation are being embedded in operational plans.[2]

Such capabilities have become increasingly important as the U.S. armed forces redirect their energies away from the familiar Soviet dominated landscape of the Cold War toward the less well defined, multi-dimensional demands arising out of ubiquitous regional conflicts. The trend is particularly applicable to the Central Region, a complex collection of 19 nations that stretches from the Horn of Africa and Egypt through Jordan and the Gulf States to Afghanistan and Pakistan and which incorporates the waters of the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Gulf of Oman, and the Arabian Gulf.[3]

Maintaining security and stability in this part of the world is essential to the political and economic well-being of American and of the entire international community. Some 65 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves are buried beneath the wind-blown sands of the Gulf States—oil that provides the United States with 22 percent of its needs.[4] Western Europe 43 percent, and Japan 68 percent. Most of this oil must transit the narrow straits of Hormuz, as well as the Bab El Mandeb, and the Suez Canal—maritime choke points that can be easily blocked.

In addition to safeguarding the oil that fuels the global economy, the United States also focuses on defending freedom of navigation and access to markets, assuring the safety of U.S. citizens and property abroad, and promoting the security of friendly states within a comprehensive Middle East peace framework. Other interests include promoting respect for human rights and democratization, providing humanitarian assistance, and countering drug traffickers. We also seek to foster economic development, prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and defeat of international terrorism.[5]

* * * * *

Safeguarding these vital and enduring interests is a formidable task. USCENTCOM must undertake policies and operations in a diverse region, rich in culture, but plagued by endemic hostilities. The birthplace of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the Central Region is home to 427 million people from 17 different ethnic groups and 420 major tribal groupings.[6] Such multiculturalism is combined with border disputes, competition for resources, radical political and religious movements, economic strains, and exploding populations to provide fertile ground for both internal and external conflicts. Aggravating these sources of friction are Iraq and Iran, the gravest national threats to regional peace and stability. Both seek dominance in the Gulf and have frequently attempted to intimidate their weaker neighbors.

UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter / Army Aviation archive photo

After losing more than half of its conventional military strength in the Gulf War, Iraq is overcoming crippling international economic sanctions and intrusive United Nations inspections to maintain the largest collection of ground forces in the region. Furthermore, as it did during its invasion and subsequent occupation of Kuwait in 1990, Iraq repeatedly demonstrates the capability to mobilize rapidly and to move large troop formations quickly to threaten Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

While Iraq remains the near-term challenge, Iran is the long-term threat. Fifteen years after seizing power, Iran’s revolutionary regime continues its quest to dominate the Gulf and to become the spiritual leader of the Islamic world. With its vast oil reserves, many engineers and technicians, and large population, Iran has been able to overcome internal unrest and economic malaise to pursue its ambitions. It has purchased submarines, attack aircraft, and anti-ship missiles while underwriting Islamic extremists worldwide, militarizing disputed islands, in the Strait of Hormuz, and seeking to disrupt the peace process.

These threats are inflamed by the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Iraq and Iran have joined several other states worldwide trying to acquire ballistic and cruise missiles and chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. The difficulty of their quest is made easier by the willingness of nations such as Russia and other former Soviet republics, North Korea, and China to sell advanced weaponry to anyone with hard cash. This situation is made even more worrisome by the ease with which older systems can be improved through purchases of “off-the-shelf” technology. As potential foes procure and upgrade sophisticated systems and harden and conceal command and control, launch, research and development, and storage sites, our military forces will have increasingly greater difficulty finding and striking them when required.

* * * * *

In devising a military strategy and associated campaign plans to contend with these threats, USCENTCOM must compensate for lines of communication that stretch more than 7000 miles from the United States. Potential adversaries, on the other hand, need only travel 100-150 miles to reach Kuwait and the Saudi oil fields. This time-distance problem is further aggravated by the absence of formal agreements and alliances with local states, the need to balance military requirements with cultural sensitivities, and demands of having to fight, maintain, and communicate in some of the world’s harshest climates and most rugged terrain.

To meet these trials, we at USCENTCOM engage in activities that satisfy near-term requirements and offer the basis for confronting long-term threats. A major foundation for these efforts is the strong relations forged with our regional friends over the years. We have been able to address with them our mutual security concerns while also gaining access to the region. It is this access that secures our interest and provides the operational capabilities needed to deploy and employ our military force. From this base, we pursue an array of initiatives that support our peace and wartime goals. We maintain a relatively small but lethal mix of air, ground, and sea forces forward in the Gulf and reinforce these with additional units and individuals participating in robust exercise and security assistance programs. To reduce deployment time-lines, we preposition sizeable stockpiles of supplies and equipment ashore throughout the region alone and augment these with other stocks afloat. While critical, activities in the region alone do not meet our security needs. Success in future conflicts requires that we be able to project power rapidly from the U.S. and elsewhere in the world. To meet this need, we routinely practice speedy mobilization and deployment of trained and ready units, people, and equipment. Through the cumulative effect of these activities, we promote regional peace and stability, deter hostilities, limit the intensity of conflict should deterrence fail, and fight and win wars when required.

While we seek to employ these measures to deter conflict by convincing would-be aggressors of the futility of using force to achieve hostile aims, we recognize that our success requires being able to fight and win on the battlefield. In such circumstances, we expect U.S. forces operating in the complex strategic environment of the Central Region to be adept at waging high-intensity warfare with coalition partners. Units and leaders that can meet this operational challenge possess the flexibility and versatility to handle threats spanning the conflict continuum.

In this context, Army aviation offers incomparable qualities. Speed, firepower, precision, maneuverability, flexibility, mass, and surprise—around the clock and in adverse weather; these are its trademarks. Army Aviation introduces onto the battlefield new concepts and technology that allow us to realize the indirect approach in warfare on an unprecedented and massive scale.[7]

To underscore this last point, consider the dramatic maturation that we have experienced in vertical envelopment, a modern form of the indirect approach.

Back on June 6, 1944, American paratroopers of the 101st and 82nd Airborne divisions grimly prepared to jump or fly gliders into Nazi occupied France. Green lights went on as aircraft passed over what the pilots believed were the designated objectives.

Fog, flak, and imperfect navigation caused many of the aircraft to miss their designated drop zones. Gliders crashed far from their desired landing sites. Paratroopers landed in pastures, orchards, and towns. They drowned in canals and rivers.

Some came under a withering hail of bullets as they struck the ground. Others wandered aimlessly for hours looking for friend and avoiding foe.

General J.H. Binford Peay III / Wikipedia Commons

It took all night to assemble units. Throughout the early morning, small bands joined up and moved toward assault objectives. Those that did not land in their assigned drop zones carried out the missions assigned to whatever sector they found themselves in. This largest U.S. airborne assault up to this point in history shocked the Germans. It was audacious. It disrupted Nazi command and control. It obstructed the movement of enemy reserves and artillery. And it demoralized the German defenders.

At the same time, the airborne drops revealed grave shortcomings. While the dispersion of the paratroopers confounded enemy defenders, it undercut the concentration of the meager combat power of the American troops. Lacking firepower and ground mobility, the paratroopers were unable to reach many of their assault objectives. More vigorous Nazi counterattacks would have routed them. The operation was also costly. The 101st, for example, suffered 3,800 casualties, nearly one-third of its strength, by the end of June 1944.

Compare the D-Day airborne operations with the performances of all our aviation units—lift, reconnaissance, assault, attack, medical, and command and control—during Operation: DESERT STORM.

This was the realization of the dream of aerial envelopment, conceived by the World War II generation and nurtured by American warriors in the jungles of Vietnam.

Speed, mass, precision, and shock, which were unattainable with the dispersed airborne landings in Normandy, were achieved by leveraging the technological reliability and pinpoint accuracy of the Black Hawk, Chinook, Apache, Cobra, Iroquois, and Kiowa helicopters in some of the world’s harshest climates and most difficult terrain.

As we look to the future of war in the Central Region, we will build on our recent wartime experience. Capitalizing on advances in avionics, communications, computers, fire control and delivery systems, munitions, and mobility, we will be able to achieve an unprecedented fusion of intelligence, fires and maneuver.

Comanche, the centerpiece of the aviation modernization effort, will scout the battlefield round the clock and in all-weather, sharing information and imagery with other ground, air, sea and spaced-based sensors.

From these capabilities, friendly forces will share a remarkable extended view of the battlefield and possess the tactical means to reduce target acquisition and engagement times dramatically. Armed with these tools, senior commanders will exploit the lethal punch of the Longbow Apache and use of powerful fires from tactical aircraft, artillery, and ground maneuver forces to pummel the enemy across the width and depth of the theater operations at an extraordinary pace.

Simultaneously, UH-60 Black Hawks and CH-47 Chinooks or a follow-on heavy lift bird, will rapidly project infantry and artillery deep into the heart of the enemy, where they will block lines of communication and wreck reserves. Whatever can be seen will be immediately destroyed. These cascading, simultaneous, punishing attacks will lay waste to the enemy’s weapons and collapse his will to fight.

The depth and destructiveness of these vertical envelopes transcend the tactical level of war. Striking the enemy where he is most vulnerable and least prepared to respond is “operational level warfare.” Aviation technology offers the theater commander new opportunities: maneuver and firepower to cripple enemy strategic systems and sites, control operationally significant terrain, and destroy the enemy’s operational forces. So endowed, today’s senior commanders carry the key that unlocks the mystery of the indirect approach on a revolutionary scale that would be the envy of a Lee or MacArthur.

While technological breakthroughs in aviation are an essential part of this transformation in warfare, we must remember that operational success will continue to rest, as it always has, on the shoulders of our young leaders—leaders with highly honed tactical and technical skills; leaders cut from the same mold as Lee, Gavin, Ridgway, Taylor, Howze, Kinnard, . . . and other Army aviation and air assault visionaries. In the words of author Tom Wolfe, we will need aviators with the “Right Stuff.”

“The “Right Stuff.” One either has it or one doesn’t. It is a quality that combines speed of mind, dexterity, common sense, courage, physical and mental strength and determination. It involves the willingness to take risks and a yearning to be the best. Army Aviators brandish these rare traits every day as they take-off in a hurtling piece of metal comprised of imperfect mechanical components. They must contend with questionable weather, the trials of fatigue, and well-armed opponents. And they do this 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

As Tom Wolfe posits, those who pass this seemingly endless series of trials join the ranks of the splendid few at the top—the top “brotherhood and the Right Stuff.” We are fortunate that the ranks of Army aviation swell with men and women with the “Right Stuff”—soldiers endowed with the traits required to defend our nation and that announce to the world that America’s armed forces stand ready to do what must be done to win anywhere, today and tomorrow.

Source: See pages 8, 10, 34-36, “Triumphant Flight: Army Aviation in the Central Region,” Army Aviation, Vol. 45, No. 1, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport , Ct., January 31, 1996.

Endnotes

- General George S. Patton, Jr’s pronouncement is pure Sun Tzu:

Point 4: “When the enemy is at ease, be able to weary him; when well fed, to starve him; when at rest, to make him move.

Point 5: “Appear at places to which he must hasten; move swiftly when he does not expect you.

Point 15: “For if he prepares to the front his rear will be weak, and if to the rear, his front will be fragile. If he prepares to the left, his right will be vulnerable and if the right, there will be few on his left. And when he prepares everywhere he will be weak everywhere” See pages 96 and 98, Chapter VI, “Weaknesses and Strengths,” The Art of War, by Sun Tzu. Besides General George S. Patton, Jr., Mao Tse-Tung was heavily influenced, too, by Sun Tzu. Read On Guerrilla Warfare by Mao Tse-Tung. Editor’s note. - Looming in the background of any war being planned as a short, sharp conflict, are the words put forth again by Sun Tzu: “For there has never been a protracted war from which a country has benefited. Li Ch’uan: The Spring and Autumn Annals says: ‘War is like unto fire; those who will not put aside weapons are themselves consumed by them.’” See page 73, Chapter II, Point 7, The Art of War, by Sun Tzu. Editor’s note.

- The areas in question, as put forth by General Peay, are products, for the most, of the collapse of the dominance by 1945, by the once powerful White, Christian European colonial powers, which unleashed such forces as Revolutionary Nationalism. Editor’s note.

- In addition to the over-prepondering reality that oil is priced in Dollars, which is a large reason that the Dollar is the world’s reserve currency. The struggle, then, is every bit as much financial as it is material. Editor’s note.

- An ongoing and seemingly endless dilemma is, “about 250 million out of 400 million across 10 Arab countries, or two-thirds of the total population, were classified as poor or vulnerable.” The Middle East, then, is one of the most unequal in the world, leaving many families in poverty for generations. And with governments that cannot or will not provide basic services and economic opportunities, especially for the large younger segments across the Middle East demographic, many turn to the such actors as the Muslim Brotherhood and Hezbollah for assistance. See page 2, “How Poverty and Inequality Are Devastating the Middle East,” by Rami G. Khouri. Editor’s note.

- In an area with only one percent of the world’s fresh water, the precipitous rise in population growth, together with economic inequality and authoritarian regimes, virtually assures stormy waters ahead. For instance, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen, in 2018, were peopled by some 484 million souls; by 2030, 581 million and by 2050, 724 million (Source: UNICEF, 2018.). See page 2, “Middle East Demographics to 2030,” by Paul Rivlin.

- The Airmobility concept enabled conventional troops to operate as guerrillas; from the perspective of being able to strike an enemy’s rear and then quickly retire to another front; or, attack a flank to put an enemy force off balance, perhaps in preparation for a major attack or to cover the withdrawal of a main force. The battle of Ia Drang, November 1965, offers a case in point. Here elements of 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) were inserted by helicopter behind the enemy’s front. Control of the Third Dimension enabled the constant supply and support of the skycav units inserted into enemy-controlled territory. By comparison, guerrillas freely move by foot, for the most part. They strike and then withdraw. But many of their caches of supply and equipment are sedentary, therefore at risk of confiscation and/or destruction. For the skycav soldiers, their element of supply and mobility is mobile, and as long as control of the air is assured, movement and control of the battlefield is greatly enhanced.

Bibliography

- Khouri, Rami G., “How Poverty and Inequality Are Devastating the Middle East,” Carnegie Corp of New York, www.carnegie.org/topics/topics-article/why-mass. . .

- Peay, General J.H. Binford, “Triumphant Flight: Army Aviation in the Central Region,” Army Aviation, Vol. 45, No. 1, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., January 31, 1996.

- Rivlin, Paul, “Middle East Demographics to 2030,” The Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies, Tel Aviv University, August 21, 2019. Dayan.org/content/middle-east-demographics-2030

- Tzu Sun, The Art of War, Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford, 1963. Introduction by Samuel B. Griffith, with a Foreward penned by B.H. Liddell Hart. The Art of War was reputedly written by Sun Tzu some 2,500 years ago.