AMRDEC Tech Talk —By Mr. Robert R. Copeland and Mr. Anthony J. Mance

After decades of research and attempts to define the psychological phenomenon known as “situational awareness” (SA), there still appears to be much confusion as to what it is, what it means, and how SA applies to Army Aviation.

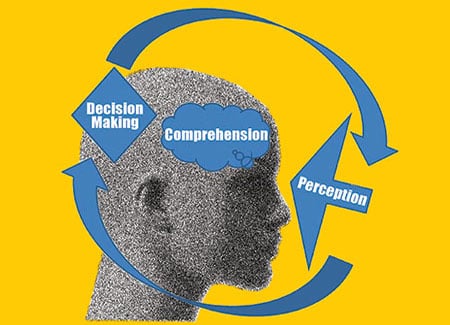

First, SA is not a thing; it is a psychological process. It is not an end-state; it is an iterative process of perception, understanding, and decision-making. There are numerous developers who proclaim the benefits of their particular device and espouse that their “tool” is better because it’s used for situational awareness. So, if a device is for “situational awareness,” it has to be good, right? The term itself implies goodness. Pilots will be better, faster, and more efficient. However, from an airworthiness perspective, we must be able to understand and substantiate the impacts of the display of information and to understand how flight safety may be affected. As such, we must first all be speaking the same language. A common definition is needed. We must also understand the difference between certain, specific information and general information. Lastly, we must determine how the presentation of erroneous, misleading, or potentially conflicting information may impact flight safety, crew performance, and training.

What is SA?

|

SA is the basis for how individuals perceive and process new information, make real-time decisions, and react to dynamic situations. A broader definition that is used in the standardization of aircraft display information is:

“Situational awareness is the ability to identify, process, and comprehend critical, perceived elements of information in one’s environment in order to make decisions about a future state and/or needed actions.”

Any information that is presented to the crew can affect situational awareness. If information is presented “for situational awareness,” then performance must be demonstrated to prove that the information increases SA, does not increase workload, or does not present hazardous or misleading information to the crew. SA is affected by environmental factors, operator workload, physiological/psychological stress, previous experience or training, and what information is available at that moment. The information displayed is not SA, only a contributing portion to the overall process. When, how, and what information is perceived affects the comprehension of its meaning, and how that information is perceived and comprehended has a direct bearing on projecting future states. The basic premise here is that more is not necessarily better. If information is not presented (layout, format, and content) in such a way that it is easily understood within the context of the task to be performed, then, by the very definition of SA, we have introduced additional workload and, thereby, have degraded the very process we were trying to improve. Now add the possibility that the information itself is bad, outdated, latent, or otherwise misleading, and we have created a potentially hazardous situation.

OK, But Does It Really Matter?

Well, maybe! The real question is whether the information shown on that SA device has the appropriate reliability, integrity, and accuracy, and whether the information interferes with, supersedes, or otherwise conflicts with information from the primary, approved systems on the aircraft. If crews need to constantly monitor or crosscheck these devices for discrepancies with their primary systems or if they have to parse potentially “good” information from the bad, then we have just seriously degraded SA and made things worse.

All in all, “caveat emptor” (buyer beware)! So before you get too excited about the latest technology, make sure you understand the pitfalls of information displays and their inherent risks, especially when the pretty picture seems so compelling. If there is an operational need or a new requirement, the Army Aviation enterprise is prepared to handle it; however, because the speed of the acquisition cycle falls behind the speed of new developments, cockpits are being inundated with these SA devices. If it’s just a new and improved device or claims the capability “for situational awareness,” be prepared to face some possible pitfalls. The generalized term “for situational awareness” will continue to be used as a catch-all label for any information that is desired by flight crews but is not qualified for the intended use. Ensure that systems claiming to enhance SA actually do without increasing workload or presenting potentially hazardous or misleading information. The challenge for all of us will be delineating the real “value-added” enhancements and capabilities of a well designed information display from the marketing double-speak and pretty pictures that sell fast but fall short.

Mr. Robert R. Copeland is an experimental psychologist and the Aviation Engineering Directorate’s subject matter expert on situational awareness and human performance; Mr. Anthony J. Mance is the chief of the Aircrew Integration Branch, Mission Equipment Division; both at Redstone Arsenal, AL.

Courtesy of AMRDC AED

Courtesy of AMRDC AED