Looking Back, March 2024

By Mark Albertson

Parochial Thinking / Seeds of Contention

On June 4, 1920, the National Defense Act was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson. The Act saw fit to organize the United States Army as an aggregate of three subdivisions: The Regular Army, National Guard and the organized reserves of civilians or Officers’ and Enlisted Reserve Corps. The Regular Army was to have a manpower strength of 17,726 officers and 280,000 enlisted. Of course, this was dependent upon Congress and whether it appropriated enough money for a ground force of even this size. And this is precisely what the august body did not do, as pointed out by Rebecca Robin Raines in her study of the Signal Corps, Getting the Message Through:

“Despite a booming economy, the Army did not prosper during the ‘Roaring Twenties.’ Budget-minded Congresses limited the Regular Army to 12,000 commissioned officers and 125,000 enlisted men, only slightly more than had been in uniform when the United States entered World War I. Eventually Congress reduced enlisted strength to 118,000, where it remained until the late 1930s. Army appropriations, meanwhile, stabilized at around $300 million, about half the projected cost of the defense act if fully implemented. The Army remained composed of skeleton organizations with most of its divisions little more than ‘paper tigers.’”[1][2]

The General Staff lost much of its authority to the Bureau Chiefs again. “Specifically, the General Staff was to prepare plans for mobilization and war, ‘to investigate and report on the efficiency and preparedness of the Army,’ and to ‘render professional aid and assistance to the Chief of Staff and the Secretary of War.’ It was not to assume or engage in of an administrative nature that pertains to the established bureaus of offices of the War Department which might imperil [their] responsibility or initiative, impair their efficiency, or unnecessarily duplicate their work.”[3]

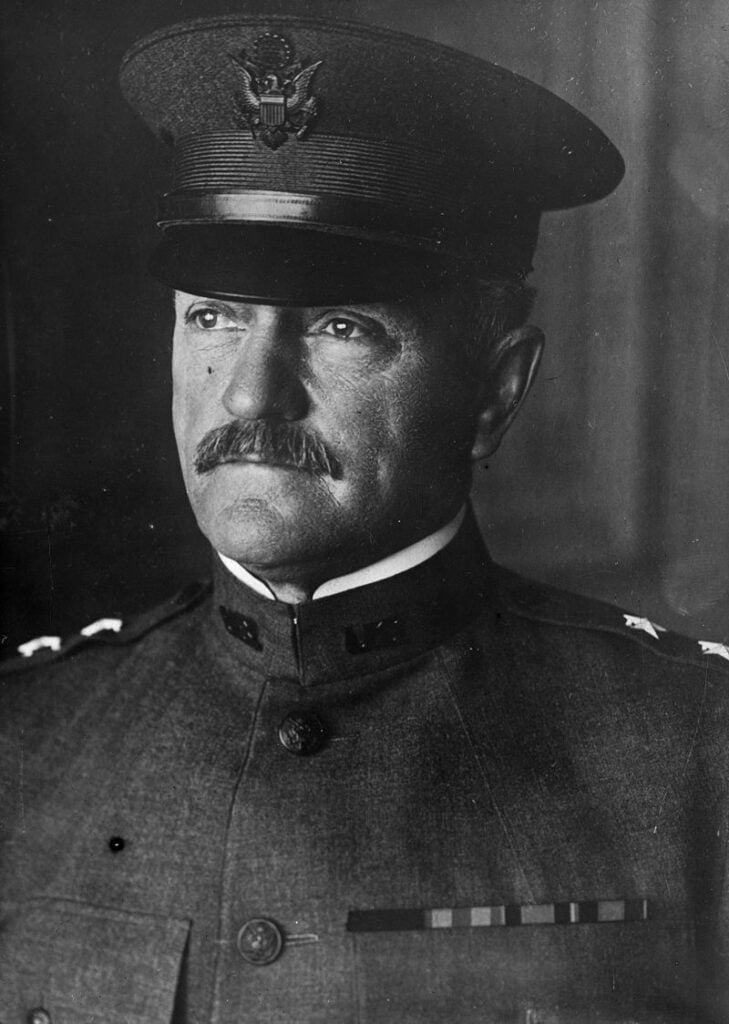

General of the Army, John J. Pershing. As Chief of Staff, he felt frustrated that his authority was blunted by the Bureau Chiefs, stifling innovation in the U.S. Army following World War I.

General of the Army, John J. Pershing. As Chief of Staff, he felt frustrated that his authority was blunted by the Bureau Chiefs, stifling innovation in the U.S. Army following World War I.

The Chief of Staff was not merely demoted in stature, he shared power with the Bureau Chiefs who exercised prerogatives with regards to departmental budgets, and who could and did run to Congress when their turf was “threatened.” General Pershing, who was Chief of Staff following World War I and who was used to wielding his authority as an overall commander, felt frustrated at having his authority compromised by the Bureau Chiefs.

The National Defense Act saw the Chemical Warfare Service added to the masthead of Army branches. This was a reflection of the importance chemical weapons came to enjoy during the Great War. Ditto the Air Service, which became an Army branch with a manpower strength slated for 1,514 officers and 16,000 enlisted. In fact, the growing importance of airpower can be seen in 1926 with the advent of the U.S. Army Air Corps. However a lack of understanding of the importance of Combined Arms Warfare became clearly evident with the demise of the Tank Corps.

Dwight Eisenhower, future Commander-in-Chief of Allied armies in Europe, was threatened with court-martial for his written and verbal support of a greater use of the tank in 1920.

Dwight Eisenhower, future Commander-in-Chief of Allied armies in Europe, was threatened with court-martial for his written and verbal support of a greater use of the tank in 1920.

The fledgling Tank Corps was the result of the promise offered by the tank as a medium of mobile warfare. But with the National Defense Act of 1920, the Tank Corps was consigned to the Infantry.[4] This retarded the potential of the tank as a viable component of an American Combined Arms Team. Much of the postwar outlook on armor in the United States was based on experience garnered from the battlefields in France. The U.S. Army, like the French Army, came to view the tank as an infantry support weapon. This line of thinking was based upon the unreliable pot-bellied stoves which literally crawled across the churned up French landscape. Battlefields pockmarked with thousands of water-filled shell craters which, at times, were traversed more quickly by the infantry than the tanks which had been sent to support the advance.[5] Indeed, American thinking was so parochial, that Dwight Eisenhower, in 1920, “was rebuked by the U.S. Army’s Chief of Infantry after having advocated a stronger tank force for infantry divisions and then was threatened with a court-martial if he continued publishing in that vein.”[6]

The Germans, having lost the war as well as being on the receiving end of a weapon that helped to breach their defenses, came to a different conclusion. Officers such as Ernst Volkheim, Oswald Lutz and Alfred von Vollard-Bockelberg gave serious thought to the possibilities of the tank as a spearhead in a new form of mobile warfare that was to become known as Blitzkrieg. Aircraft, artillery and infantry would blast a hole in the enemy’s front. The breach would be exploited by the swift-moving panzer columns, taking the war to the enemy’s rear. This new mailed fist would not be equipped with the battlefield plodders of the previous conflict; rather, speedy, radio-equipped armored fighting vehicles able to attain speeds of 25 to 30 mph. This meant supporting infantry had to be motorized to keep pace with the advance. And the armored spearheads would enjoy Close Air Support provided by Goering’s Luftwaffe.

Some Soviet theorists drew lessons not to unlike those of the Germans. Lessons they would share with their former enemy as a result of the 1922 Treaty of Rapallo. Soviet Deep Operations called for deep thrusts into the enemy’s front. And the Soviets would eventually latch on to the tank as the vehicle for advance. One of those who championed mechanization was Mikhail Tuchachevsky, veteran of World War I, the Civil War and later marshal in the Red Army. But just how advanced Soviet thinking was in comparison to America can be seen in their view of the tank.

According to Eddie Rickenbacker, the Shturmovik was the best ground support/tank busting aircraft of World War II. Owing to the prominence of strategic aviation in the U.S. Army Air Corps/Army Air Forces, such a plane of similar effort would not be entertained. The Il-2 went on to become the most produced combat aircraft in history at 36,183 copies.

According to Eddie Rickenbacker, the Shturmovik was the best ground support/tank busting aircraft of World War II. Owing to the prominence of strategic aviation in the U.S. Army Air Corps/Army Air Forces, such a plane of similar effort would not be entertained. The Il-2 went on to become the most produced combat aircraft in history at 36,183 copies.

During the later 1920s and early 1930s, American designer J. Walter Christie was designing light and medium armored fighting vehicles which were miles ahead of the battlefield plodders of the Great War. The War Department evinced little interest, unlike the Soviets. The Russians bought copies of Christie’s designs and during the 1930s, produced a string of models that would eventually evolve into the superlative T-34. This medium tank was without a doubt the best armored fighting vehicle produced on the Allied side during World War II. And when mated with the IL-2 Shturmovik—arguably the best ground support plane of the Second World War—gave the Soviets a formidable battlefield punch.[7]

The American lack of foresight in tank design, coupled with the lack of appreciation offered by the potential of armor, was unveiled for all to see with the new reality of mobile warfare on September 1, 1939. The Wehrmacht’s crushing of western Poland was a wake up call; a view of the new reality of modern war that was bolstered by the fall of France in June 1940. The latter is of particular importance because the U.S. Army came to view the tank just like the French Army, as an infantry support weapon. And despite the fact that tanks like the French Char B could take more punishment and dish it out in comparison to German types, the vaunted French Army went down in decisive defeat. And this despite the fact the Germans operated at a deficit of some 900 tanks versus the Allies, they massed their armor at those points chosen for their armored spearheads. This local superiority backed by Close Air Support aviation burst out if its tactical confines to produce a strategic victory . . . the humbling of France and the Low Countries. And to add insult to injury, the British Army had been kicked off the Continent barely a month after the start of the campaign. A vindication, to be sure, of an earlier prognostication by Hitler. “The next war would not be fought like the last war.” In this the Fuhrer was proved correct; for unlike the French, Hitler was fighting to the timetable of 1940 not 1914.

Hitler’s lightning victories in 1939 and 1940 were a vindication of Billy Mitchell’s ideas of air supremacy. Luftwaffe fighters swept the skies of enemy pursuits while bombers and ground support squadrons worked over enemy airfields, supply columns, troop concentrations, rail lines and rolling stock. Ju-87 (Stuka) dive-bombers and German artillery worked to blast the way open for the swift-moving panzer columns. Airpower, infantry, armor and artillery working together to produce victory. In other words, modern Combined Arms Warfare.

* * * * *

Air Corps Act of 1926

With the Air Corps Act of 1926, the Air Service attained a level of enfranchisement not previously enjoyed. For the evolution towards an independent air force can be seen with the progression of Army airpower since it early days:

- Aeronautical Division of the Signal Corps.

- Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.

- Division of Military Aeronautics.

- Air Service.

- U.S. Army Air Corps.

- U.S. Army Air Forces.

- U.S. Air Force.

Free of its second-fiddle status within the Signal Corps, through its sojourn as the Air Service, the name Air Corps came to denote the next step towards autonomy. And it is important not to lose sight of this concept. For Army airpower had come from being an insignificant afterthought—featuring Ben Foulois holding the fort as the Army’s sole pilot flying the Army’s only aircraft in 1910—to an air contingent that was to have representation on the General Staff and see to the reappointment of an Assistant Secretary of War for Air, such as there had been during the World War. In addition, the Air Corps Act called for Congress to fund an air fleet of 1,800 aircraft within five years. Indeed, since 1910, Army airpower had come a long way by 1926.

America’s aviators enjoyed a decisive advantage in their quest for autonomy: Military aviation came to be considered state-of-the-art technology. And what the battleship did for the Navy aircraft will do for the Army Air Corps. And the expression emblematic for the idea of an independent air force was the strategic bomber.

The round-the-world cruise of the Great White Fleet, 1907-1909, was seen to have justified the monies spent on the battle fleet.[8] The success of this demonstration of American sea power helped to sell the Navy to the public and cemented its image as America’s first line of defense. And the cornerstone of the sales pitch was the battleship. The battleship was the crowning achievement in weaponry of the Industrial Revolution up to that time; affixing the image in the collective mind of a floating steel fortress able to hurl tons of ordnance out to as far as the eye could see. Cutting-edge technology indicative of the Nation’s quest to see its burgeoning economic and military power able to forge its rightful place on the world stage.

Aircraft came to be viewed in a like manner. Airmen in bombers winging their way unassailably to rain down death and destruction upon an enemy’s potential to wage war was considered top-shelf technology. Airpower, like naval power, came to be seen as a way of keeping enemy forces distant. Indeed some of the champions of strategic airpower saw the Air Corps as a challenger for the mantle held by the Navy, that of the Nation’s first line of defense.

Conversely the Ground Forces enjoyed no such esteem.[9] Edgar Raines, in his Eyes of Artillery, sums up the plight of the Ground Forces pretty well: “During the years between the wars, responsibility for the organization, doctrine and training of combat arms rested in the first instance with their respective branch chiefs. They achieved their goals in these areas in part by shepherding funding requests for their branches through the War Department, Bureau of the Budget and Congress. The equipment category of the War Department budget provides eloquent testimony to the Air Corps’ favored status. In 1931, one of the few years for which detailed figures survive, the Air Corps received $35,823,473. By way of contrast the Infantry received $65,623, the Field Artillery $20,610 and the Cavalry $26,685. This was not autonomy—the Air Corps’ portion of the budget was still subject to General Staff control—but its size in comparison to the other branches did represent a substantial measure of power within the narrow confines of the War Department.[10]

The new Air Corps was to have 1,514 officers—spanning the ranks from lieutenant to colonel—and 16,000 enlisted. The aforementioned Assistant Secretary of War for Air was resuscitated to represent Army airpower needs.[11] The Air Corps Act established a commander known as the Chief of the Air Corps, with the rank of major general. He would have three brigadiers as assistants, two of which were flying officers. The budget was to be controlled by the Office of the Secretary of War.

Unlike Eisenhower, ardent proponent of an independent air force, Billy Mitchell, will be court-martialed in 1925. He will incur another setback in 1933, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt will not choose Mitchell as Secretary of War for Air.

Unlike Eisenhower, ardent proponent of an independent air force, Billy Mitchell, will be court-martialed in 1925. He will incur another setback in 1933, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt will not choose Mitchell as Secretary of War for Air.

As might be expected, the Air Corps Act did not go far enough to appease some of the ardent practitioners of airpower. One such was Billy Mitchell, by then a civilian.[12] He “intimated that in some nations, ‘air, land and water are under separate ministries,’” Obviously the Air Corps Act did not go far enough for the champion of airpower. Unlike General Mason Patrick, who observed it was “a long step in the right direction.”[13]

There is an old saying, “What‘s in a name?” Well with regards to this discussion, everything. As mentioned in the preceding pages, the name Air Corps itself denoted a certain air of independence. The march towards an independent air force during the 1930s should have been obvious. For Mitchell’s idea of an air force was to take the fight to the enemy . . . offense. This meant going beyond the battlefront to take the fight to the enemy’s territory . . . to his homeland itself. To strike at his means for waging war. To paralyze and even destroy his ability to not only produce the implements of war, but to transport them as well. This was the essence of strategic airpower. And the emphasis on strategic airpower would increase exponentially by the beginning of America’s entry into the Second World War.

Interest in strategic bombing caused a corresponding shift in Close Support-type aircraft. Single-engine types gave way to twin-engine light and medium bomber aircraft, such as the Douglas A-20. The affect of the Spanish Civil War cannot be understated here. For this tune up to the main event in 1939 instilled the belief that CAS should target airfields and anti-aircraft artillery to support strategic bombing in lieu of supporting infantry and artillery. This rationale certainly retarded the Air Corps’ development of CAS. For the United States Army Air Corps/Army Air Forces will never field a ground support/tank busting aircraft of a similar effort to the Soviet IL-2 Shturmovik. Question here is, where did that leave the foot slogger and breech loader?

Well on the heels of the first chapter of the Great War, the performance of the Field Artillery was reviewed. Major General William J. Snow, Chief of the Field Artillery (1918-1927), convened three boards: The Westervelt Board, so-named for Brigadier General William I. Westervelt, chair of the board which reviewed gun types and calibers, ammunition and transport of the Field Artillery. For the short duration America was engaged in the conflict, Yankee artillerymen relied heavily on field pieces largely of French manufacture. This was not to be in the second chapter of the Great War. For most of the recommendations on gun types and calibers put forth by the Westervelt Board were adopted by the Army.

A second board, too, chaired by Brigadier General Westervelt was the Trench Artillery Board. Like the previous effort, this commission was put together to study the affects of mortars in the Great War and to offer recommendations for the future. Among the findings was that there must be a greater reliance on light and medium calibers of mortars. Another was that the Army should make use of tubes of 160 mm and 240 mm in support of the Field Artillery; and there should be an independent Trench Artillery Branch in the Army. However in an era of military downsizing and too few dollars, little if anything was done to act upon the recommendations of the Trench Artillery Board.

Forerunner of those such as William Wallace Ford. As chair of the 1919 Hero Board, General Hero urged that organic aerial observation assets be applied to Field Artillery units.

Forerunner of those such as William Wallace Ford. As chair of the 1919 Hero Board, General Hero urged that organic aerial observation assets be applied to Field Artillery units.

The last of the trio of panels was the Hero Board, so-named for its chairman, Brigadier General Andrew Hero, Jr. This commission shared some of the same concerns as those of the Westervelt Board such as gun types and calibers, training, ammunition, supply, communications and transport. But this board also brought out the necessity of aerial artillery spotters of the organic variety.

Organic aerial artillery spotters would solve the problem inherent with the observers of 1917-1918. Here aerial observers and pilots were spotting for the field artillery as well as being assigned to other duties; hence the lack of continuity which affected their performance as spotters. Instead of rotated personnel, organic aerial artillery spotters would perform no other function but that of adjusting artillery fire. Here, it is plain to see, that a recognition of the evolution of the specialization of tasks in modern, industrialized war is taking place.

In addition, the Hero Board went a step further by recommending that artillery commanders should maintain control over their observation assets. That each division should have an observation squadron attached to it. Aerial artillery spotters should come from the ranks of the Field Artillery; same with pilots, who would train with the units to which they were to be attached. Note, though, the configuration of the Board’s recommendations: The committee’s suggestion was that the Air Observation Posts of the Field Artillery would remain two-man affairs. The Hero Board still saw things based on experience from the Great War. Understandable when one considers that the staffers of the Board were products of the era. But the fact remains that the spotter planes would be flown by two-man crews.

Undoubtedly many of the Hero Board’s recommendations were a decided step forward in the evolution of that process that would produce William Wallace Ford’s Air Observation Post, and to which Army Aviation would be the eventual result. But it also sowed the seeds for that contention between the breech loaders and airmen for control of the Air Observation Post with America’s entry into war, 1941. A political contest over roles and missions between the Army and the Air Force that would last for decades to come. . .

Endnotes

[1] See page 218, Chapter 6, “Between the Wars,” Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, by Rebecca Robin Raines. Also see page 408, Chapter 19, “Between the World Wars,” American Military History, by Maurice Matloff.

[2] See page 16, Chapter 11, “Prewar Settlement and Its Effect on the Army,” U.S. Army in World War II, The War Department, Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans & Preparations, by Mark Skinner Watson. Watson basically agrees with Raines. In 1923, the U.S. Army totaled 131,959 men. For virtually all of the interwar period, American manpower strength in the Army never approached the 297,726 men specified (17,726 officers and 280,000) enlisted. In 1940, U.S. Army strength was at 267,767. It jumped in 1941 to 1,460,998 with the growing threat of war.

[3] See pages 50 and 51, Chapter 1, Special Studies: From Root to McNamara, Army Organization and Administration, by James E. Hewes, Jr.

[4] See page 409, Chapter 19, “Between the World Wars,” American Military History, by Maurice Matloff.

[5] In an effort to defend the tank’s value by expounding on its wartime use, George Patton published an article in the Infantry Journal, May 1920. In pleading the Tank Arm’s cause, he showcased the tank as supporting infantry in overcoming or circumventing the stalemate of trench warfare. He did not, however, elaborate on the tank as the vehicle of battlefield mobility as it would come to be used in World War II. This was hardly an appreciation of the view held by J.F.C. Fuller of Britain. His “Plan 1919” saw masses of armor striking deep into the enemy’s rear as a way of sowing mobility on the battlefield.

[6] See page 141, Chapter Six,” The Development of German Armor Doctrine,” The Roots of Blitzkrieg, by James S. Corum.

[7] Famed American World War I ace, Eddie Rickenbacker, observed the Shturmovik and stated, “that it was the best aircraft of its type in the world.” Stalin chimed in with, “Our Army needs the IL-2 as much as it needs bread, as much as it needs the air it breathes.” See pages 12 and 13, The Ilyushin IL-2, by Witold Liss, Profile Aircraft No. 88, Profile Books Limited, UK, March 1982.

[8] Refer to They’ll Have to Follow You! The Triumph of the Great White Fleet, by Mark Albertson.

[9] The Army’s image was negatively impacted during the summer of 1932, with the suppression of the “Bonus Marchers.” See pages 412 and 413, Chapter 19, “Between World Wars,” American Military History, edited by Maurice Matloff. “The most notable domestic use of Regular troops in the twenty years of peace happened in the nation’s capital in the summer of 1932. Some thousands of ‘Bonus Marchers’ remained in Washington after the adjournment of Congress dashed their hopes for immediate payment of a bonus for military service in World War I. On July 28, when marshals and police tried to evict one group encamped near the Capital, a riot with some bloodshed occurred. Thereupon President Herbert C. Hoover called upon the Army to intervene. A force of about 600—cavalrymen and infantrymen with a few tanks—advanced to the scene under the leadership of Chief of Staff MacArthur in person, two other generals, and, among junior officers, two whose names would in due course become much more familiar, Majors Dwight D. Eisenhower and George S. Patton, Jr. The troops cleaned up the situation near the Capital without firing a shot, and then proceeded with equal efficiency to clear out all of the marchers from the District of Columbia. From a military point of view the Army had performed an unpleasant task in exemplary fashion, and with a few minor injuries to participants; but the use of military force against civilians, most of them veterans, tarnished the Army’s public image and helped to defeat the administration in the forthcoming election.”

[10] See page 15, “Prologue,” Eyes of Artillery: Origins of Modern U.S. Army Aviation in World War II, by Edgar F. Raines.

However the reader is cautioned not to construe the situation in the early 1930s as a one-way street for the Air Corps. Despite the budget numbers reported by Raines, the Air Corps did not yet have the bombers to wage a strategic campaign. Far from it. But even more important, the examples of Mussolini’s air force in Abyssinnia, the Japanese in China, German and Italian bombers in Spain were as yet to occur. Such events in a few years would bolster the arguments posed by the practitioners of bombing; that is, carrying war to the enemy’s homeland.

[11] The position of Assistant Secretary of War for Air did not give the new Air Corps the hoped for latitude within the War Department. For as explained on page 79, Chapter III, “Creation of the Army Air Corps,” Organization of Military Aeronautics, Army Air Forces Historical Studies No. 25, “The Air Corps was to be under the immediate supervision of the Secretary of War in spite of the fact that the air faction had repeatedly requested administrative freedom from War Department dictation. True, an additional Assistant Secretary of War to be appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, was provided for in the bill; the implication was that he, instead of the Secretary of War, should have the direction of the new corps, but since his duties were not specifically outlined, his power was necessarily restricted to that which might be delegated to him by his superior. The budget also was to be managed entirely from the office of the Secretary of War.”

[12] Billy Mitchell resigned from the Army on January 27, 1926, following his court martial on December 17, 1925. However a potential for righting this blow against Mitchell has been put forth by Roger Burlingame with reference to Mitchell entering government as a representative of airpower:

“In 1932 he had high hopes of a position in which he could work actively for airpower in the government. As a result of his repeated testimony certain concessions had been made. The Air Service had been made the Army Air Corps and given more autonomy, or changes to operate on its own. It had been permitted high-ranking officers—even generals such as the enthusiastic air-minded Frank Maxwell Andrews. But most important to Mitchell, a new office had been created in the War Department called Secretary of Air. When the overthrow of the Republicans came in November, Mitchell believed that he would be given the job. He was, after all, a Democrat by inheritance and faith; he had not fared well in Republican hands.

“Naturally [he wrote his friend General Fechet] I will have something to say in the councils of the Democratic Party. As soon as Franklin Roosevelt is relieved from his job as Governor of New York, I am going to take up the whole matter of national defense with him. . . I have plans already worked out for these things and when they are made public, they will certainly make some people jump.

“What followed was perhaps the greatest disappointment of Mitchell’s life. Everywhere during 1933, the rumor ran that the post of Assistant Secretary of Air would surely be given him as compensation for what he had suffered and to bring about real reform in air defense.

“If the job is offered you [wrote his old flying friend] for God’s sake accept it and take out the Air Corps . . . and Civil Aviation that our broken bodies has made possible out of the hands of politicians. . . .

“When the new President came into the White House, the Mitchells were invited to lunch. Mitchell went by himself for several interviews. Mr. Roosevelt was always cordial. Mitchell’s visits were reported to the press. It was repeatedly stated that the job was practically in his pocket. Influential members of Congress and advisors to the President recommended his appointment. Yet it was never made.

“Several theories about it have been advanced. It is said that Roosevelt was so strongly under the influence of the Navy that he could never bring himself to favor Mitchell. Plausible explanation perhaps; yet, the President proved air-minded in the end: for 1941 and 1942 the sky became black with planes under his urging; he advocated unity of command in the field and independent strategic air missions in World War II. But in 1933 he was still in love with ships. His desk and the walls of his White House office were covered with pictures and models of them; there were no airplanes there in 1933.” See pages 137 and 138, Chapter 15, “Vision of the World,” General Billy Mitchell, by Roger Burlingame.

Going beyond Burlingame’s analysis, one is certainly left with the possibility here, that FDR understood his predicament. The Army and Navy were institutions, reactionary institutions; institutions whose importance had been inflated by the World War. By 1933, Hitler had attained power in a resurging Germany. The Japanese had invaded Manchuria two years before. Mussolini and his Fascists had taken control of Italy. Stalin was taking the Soviet Union through the hellish episode of Collectivization and Forced Industrialization.

At this early period in his presidency, FDR needed the support of the Army and Navy. So FDR was not going to put into government a strong-willed individual ready to ostracize such pillars of power and perhaps publicly flaunt their shortcomings. Such transgressions were not to be rewarded with a seat at the table of power.

[13] See page 60, Autonomy of the Air Arm, by R. Earl McClendon.

Bibliography

Albertson, Mark, They’ll Have to Follow You! The Triumph of the Great White Fleet, Tate Publishing & Enterprises, LLC, Mustang, Oklahoma, 2007.

Army Air Forces Historical Studies: No. 25, Organization of Military Aeronautics, 1907-1935, Prepared by the Assistant Chief of Air Staff Intelligence, Historical Division, Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell AFB, Alabama, Report Date, December 1944.

Burlingame, Roger, General Billy Mitchell, Champion of Air Defense, Signet Press, 1956.

Corum, James S., The Roots of Blitzkrieg: Hans von Seeckt and German Military Reform, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, 1992.

Hewes, James, E., Jr., Special Studies: From Root to McNamara, Army Organization and Administration, CMH Pub 40-1, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1975.

Kirkpatrick, Charles E., Writing the Victory Plan of 1941: An Unknown Future and a Doubtful Present, World War II 50th Anniversary Commemorative Edition, CMH Pub 93-10, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1992.

Liss, Witold, The Ilyushin IL-2, Aircraft Profile No. 88, Profile Books Limited, Berkshire, England, March 1982.

Matloff, Maurice, General Editor, American Military History, Army Historical Series, Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1969.

Messenger, Charles, The Blitzkrieg Story, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1976.

Miller, Donald L., Masters of the Air, Simon and Schuster, Inc., New York, NY., 2006.

Munson, Kenneth, Aircraft of World War II, Doubleday and Company, Inc., Garden City, New York, 1968.

Raines, Edgar F., Jr., Eyes of Artillery: The Origins of Modern U.S. Army Aviation in World War II, Army Historical Series, CMH Pub 70-31-1, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 2000.

Watson, Mark Skinner, The War Department, Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans and Preparations, CMH Pub 1-1, U.S. Army in World War II, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1991. First published in 1950.