Looking Back, April 2025

By Mark Albertson

Operation: KIKUSUI

* * * * *

“We are 16 warriors manning the bombers. May our death be as sudden as the shattering of glass, . . . from the letter of a Kamikaze pilot.”[2]

* * * * *

It was 80 years ago, April 1, 1945, that Operation: ICEBERG commenced. GIs and marines waded ashore to nary the expected opposition, unlike at Tarawa, Saipan, Guam, Peleliu and a half a hundred other places. The marines struck out for the northern half of the island, encountering light resistance; while the Army, moving south, too, faced light resistance. Suddenly the Army ran up against a wall of fanatical Japanese who were well dug in. Casualties mounted quickly. Up north, the leathernecks reversed course and hurried south to assist their brother soldiers. They, too, began to incur heavy losses on the Shuri Line.

Soon the battle of Okinawa, the final major battle of World War II would, in just eight weeks, become the third costliest battle in American history.[3]

Yet while the marines and soldiers ashore waged the bitter struggle against the seemingly impregnable Shuri Line, the Navy trying to command the seas around the embattled island will incur its worst losses of the war. For the Japanese will unleash its most frightening weapon of the conflict, the Devine Wind or Kamikaze. The origins of which are steeped in history.

“A hurricane swept the invasion fleet of Kublai Khan to disaster off the Japanese coast in 1281. That ‘devine wind’ saved the Japanese people from foreign domination. In the last years of World War II, with the tide of Imperial Japanese expansion beaten back, a similar intervention was needed to save Japan from subjection.”[4]

By well into 1943, when it was apparent the tide was turning in the Pacific Theater, the Japanese began to consider approaches other than those of the standard varieties of waging war in an attempt to halt the growing American juggernaut. Ramming attacks (taiatari) were employed against American aircraft. Origins here go back to the Bougainville campaign, November 1943, when ramming was used by frustrated Navy pilots.[5]

An example of the above was that of Lieutenant Naoshi Kanno, 306th Fighter Squadron, 201st Air Group, 1944, based on Yap. Kanno took on a B-24. He made a head-on approach, only to find his guns were jammed. He rapidly closed his quarry, only to sheer away at the last moment, nearly brushing the bomber, only to use his propeller to cut up one on the B-24’s vertical stabilizers. The Liberator plunged into the sea. Kanno, meanwhile, nursed his sputtering Zero back to Yap.[6]

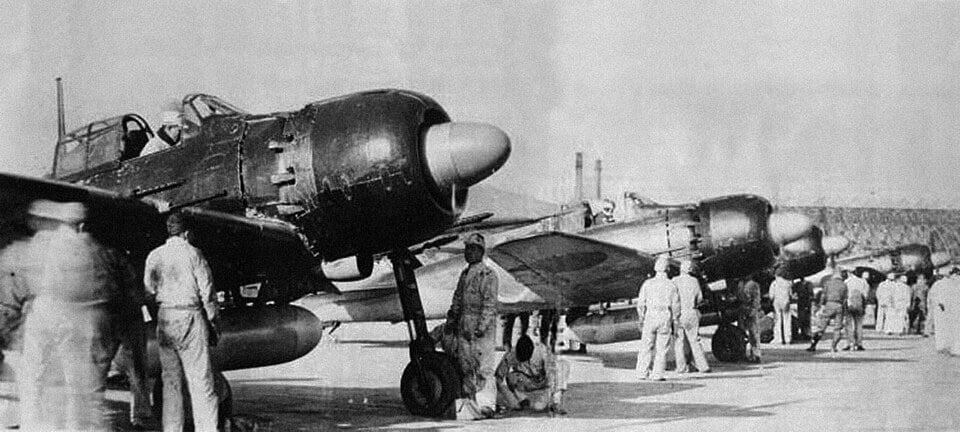

The legendary Mitsubishi Zero fighter. Once the world’s dominate carrier fighter, was by the latter stages of the war overtaken by such types as the F6F Hellcat, F4U Corsair and P-51 Mustang. The Zero, though, will be seen as the premier plane for the Special Attack Corps. Total wartime production of the A6M Zero, 10,611 machines. Does not count the 327 Rufe float Zero type.

But ramming enemy aircraft was hardly a war-winning tactic. Besides, there was certainly the chance that to bring down an enemy aircraft by ramming could cost a Japanese aircraft and perhaps even the pilot. Something, then, of greater impact was called for. Something that could cause the enemy such grievous losses, while at the same time reverse Japanese fortunes.

* * * * *

One of the early supporters of suicide as a military tactic was Captain Eiichiro Jyo, commander of the light carrier Chiyoda. In the wake of the American victory in the Philippine Sea, Captain Jyo observed, “No longer can we hope to sink the numerically superior enemy aircraft carriers through ordinary attack methods. I urge the immediate organization of special attack units to carry out crash-dive tactics, and I ask to be placed in command of them.”[7]

Yet the Japanese were fully aware that the United States was going to invade the Philippines and, with the ever growing might of American naval power, extraordinary alternatives to successfully challenge said threat had to be considered.

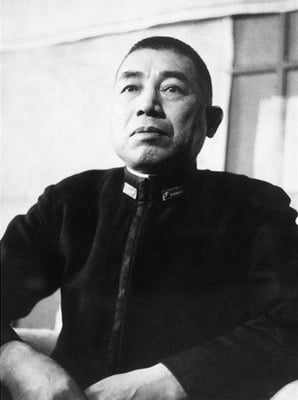

Admiral Takijiro Ohnishi, organizer of the Special Attack Corps or Kamikaze, the Devine Wind. Upon the Japanese surrender, he will commit ritual suicide, August 15, 1945, as atonement for failure and the loss of so many young men in the Kamikaze Corps.

October 17, 1944, Vice Admiral Takajiro Ohnishi arrived in Manila to take command of First Air Fleet. He convened a meeting in Mabalacat, headquarters of the 201st Air Group. Addressing a small collection of air officers, he spoke of the upcoming naval battle for the Philippines and the Imperial Japanese Navy’s growing disparity against the material advantage enjoyed by its Occidental opponent.

“In my opinion,” he continued, “there is only one way of assuring that our meager strength will be effective to a maximum degree. That is to organize suicide attack units composed of Zero fighters armed with 250 kilogram bombs, with each plane to crash-dive into enemy carriers, . . . what do you think?[8]

After a round of discussions as to how effective such a drastic action might be, Commander Assaichi Tamai was ordered to form, what would become the first squadron of the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps. The pilot assigned to lead the first attack was Lieutenant Yukio Seki. Admiral Ohnishi will sign an announcement for the new Attack Corps on October 20, 1944.

Lieutenant Yukio Seki, leads the first successful Kamikaze flight against the American amphibious forces off Samar. Leader of Shikishima flight, he crashed his Zero into the escort carrier St. Lo and sinks same.

“The 201st Air Group will organize a special attack corps and will destroy or disable, if possible by 25 October, the enemy carrier forces in the waters east of the Philippines.

Kamikaze pilots of the 201st Naval Air Group, at Mabalacat, the Philippines. The photo is reputed to be the ill-fated Shikishima flight. The pilot drinking the sake is supposed to be Lieutenant Yukio Seki, man who sinks the St. Lo. The man to the left, with his back to the camera, is supposed to be Assaichi Tamai, Seki’s immediate commander. October 25, 1944.

“The corps will be called the Shimpu Attack Unit. It will consist of 26 fighter planes, of which half will be assigned to crash-diving missions, and the remainder to escort, and will be divided into four sections, designated as follows: Shikishima, Yamato, Asahi and Yamazakura.”[9]

* * * * *

As the Kamikazes were readying themselves for devine self-immolation, history’s greatest naval battle, Leyte Gulf, had already commenced. This was the last major attempt by the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet to change the momentum of the naval war and turn back the American threat to Japan’s inner defense ring. The basic Japanese plan saw Southern Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Shojo Nishimura with 2 battleships, 3 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser and 7 destroyers come up from the south of Leyte Gulf from the Mindanao Sea through the Surigau Strait to attack the American landing forces of light carriers, destroyers and support vessels; and then from the north, Vice Admiral Takao Kurita, with 5 battleships, 10 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers and 15 destroyers would slip through the San Bernadino Strait, round Samar, then attack the light American landing forces at Leyte from the north. Japanese carriers north of the Philippines had successfully drew Admiral William Halsey’s covering force of carriers and battleships north, leaving the light amphibious forces off Leyte without protection.

Admiral Jessie Oldendorf’s task force of old battleships backed by cruisers devastated Nishimura’s southern force in the confined waters of the Surigao Strait, denying the Japanese their southern pincer in their attempt to wipe out the American landing forces. However, Admiral Kurita did round Samar to keep his appointment.

The American naval response consisting of destroyers and destroyer escorts against the big boys of the IJN became one of the stirring acts of heroism of the entire war in the Pacific, sometimes referred to as their Death Ride; in addition to which the pilots of the beleaguered escort carriers attacked like angry hornets against battleships and cruisers, even to the dropping of depth charges in lieu of bombs. Kurita will fail in his mission and eventually withdrawal. This threat will subside; but it will give way to an even greater threat, the Devine Wind.

* * * * *

October 21, 1944, Lieutenant Seki led his flight from Mabalacat to search for the reported American escort carriers off the Philippine coast. No trace was found and the flight returned to base. Then more flights, October 22, 23, and 24, again resulted in no-shows. On the 25th, though, they struck pay dirt.

Nine Zeros, four of which were escorts, had flown 3 hours and 25 minutes before they found the American escort carriers off Samar. They had made their approach as Admiral Ohnishi had suggested: Low, wave-hopping, so as to approach below the Americans’ radar. Then they climbed to their attack altitude so as to take their final plunge.

The stricken escort carrier, St. Lo, explodes after being hit by Lieutenant Seki and his Zero. Eight explosions will wrack the flattop before she took the final plunge, off Samar, October 25, 1944.

Shikishima flight of five suicide planes pushed over into attack. Flight leader Yukio Seki dove for the St Lo. Through a hail of anti-aircraft fire he plunged, undaunted. As he closed the flattop, he released his 550-pound bomb. It immediately pierced the flight deck, into the hanger deck and there exploded, cascading the elevator upwards and sending up a geyser of planes and parts; into which Seki’s Zero piled into the fiery carnage. Eight explosions ensued, tearing the baby flattop apart. An hour later St. Lo took the plunge.

Another suicide pilot closed the Kitkun Bay, strafing as he bore in. His target was the bridge, missed, zoomed over, caught the catwalk then crashed into the sea. His 550-pound bomb detonated, showering the Kitkun Bay with fragments, wounding and maiming bluejackets.

Then a pair of Kamikazes targeted Fanshaw Bay, only to be splashed by the carrier’s hot gunners.

Shikishima flight died to a man. But this did not mark the end of the attacks, for 15 dive-bombers pushed over into their death-dives. Fighters that had harried Kurita’s fleet now were vectored in to defend the carriers from this new threat. The aforementioned Kitkun Bay threw up two more fighters as well. The carrier had survived Kurita, but now came a new threat.

A Val dove for the flattop, aiming for the flight deck. The carrier’s gunners threw up withering fire. The wings of the plane came off, leaving the fuselage to pile into the sea, narrowly missing the carrier, showering her deck with fragments and plane parts.

Kalinin Bay was not so fortunate. A Kamikaze, seemingly impervious to the flattop’s gunnery crashed into the flight deck, doing grievous damage here and causing many casualties. But carrier’s plight continued as a second suicide pilot crashed into the after smokestack. Kalinin Bay, though punch drunk, survived.[10]

The four escorting Zeros of Shikishima flight-losing one after tangling with American fighters—returned to base to report the results. One American escort carrier sunk, with at least five others damaged.[11] The Kamikaze had proven itself on the field of battle. It was here to stay.

* * * * *

The Kamikaze was accepted as a tactic in response to a daunting reality: The standard methods of naval air warfare such a dive-bombing and torpedo attacks were no longer successful. This, owing in part, to the superiority of the newer American fighter planes such as the F6F Hellcat, F4U Corsair and the P-51 Mustang. In addition to the fact of superior American production, with earlier losses in warships not only replaced, but providing the United States with an unchallengeable two-ocean navy.

In the face of the above, Japanese aircraft such as the Aichi D3 Val dive-bomber with its fixed landing gear, the B3N Kate torpedo bomber had seen better days and had lost their superiority to the American Helldiver and Avenger torpedo plane. The famous Zero fighter, though still speedy and nimble, had lost its superiority to the new American fighter types. Yet it was still regarded as that plane best able to breech American defenses and cause that carnage necessary to reverse Japan’s fortunes.

Dated March 1945, an 88-page manual had been prepared by the Shimoshizu Air Unit, Chiba Prefecture, not far from Tokyo. Bearing the name of the unit commander, a Major Hayashino, it was a how-to for Kamikaze pilots. Actual title, Basic Instruction to To-Go Flyers. (To-Go was the codename for Special Attack Corps.)[12]

“Where to Crash, the Enemy’s Fatal Spots”

“Where should you aim? When diving and crashing onto a ship, aim for a point between the bridge tower and the smoke stack(s). Entering the stack is also effective. Avoid hitting the bridge tower or a gun turret. In the case of an aircraft carrier, aim at the elevators. Or if that is difficult, hit the flight deck at the ship’s stern. For a low horizontal attack, aim at the middle of the vessel, slightly higher than the waterline. If that is difficult, in the case of an aircraft carrier, aim at the entrance to the aircraft hangar or the bottom of the stack. For all other vessels, aim close to the aft engine room.”[13]

“You Are Now 30 Meters From the Target.”

“You will sense that your speed will suddenly and abruptly increase. You feel that the speed has increased by a few thousand fold. It is the long shot movie suddenly turning into a close-up and the sense expands in your face.”

“The Moment of the Crash”

“You are two or three meters from the target. You can see clearly the muzzles of the enemy’s guns. You feel that you are suddenly floating in the air. At that moment, you see your mother’s face. She is not smiling or crying. It is her usual face.”[14]

* * * * *

“The nature of the threat was self-evident, need for what was called ‘special’ measures of the highest degree of sacrifice was clear. The Chief of Staff informed the Emperor about the provisions for Kamikaze operations, which had already begun in a preliminary way, against the American fleet engaged in the bombardment (at Okinawa). The Emperor urged Admiral Koshiro Oikawa to ‘leave nothing to be desired’ in executing those plans ‘with a hard struggle by all our forces, since [they] will decide the fate of our Empire.’ Oikawa’s assurance that two thousand planes were available for suicide attacks left Hirohito clearly concerned. ‘Was that all?’ he asked, in his reedy, high-pitched voice. The admiral’s hasty reply that the Army would contribute an additional fifteen hundred aircraft did not dispel His Majesty’s puzzlement. ‘But where is the Navy?’ he asked, his tone putting an edge to the question. ‘Are there no more ships? No surface forces?’”[15] This exchange occurred in March 1945.

Thus far, since the Kamikazes had been employed, beginning with the actions off Samar to the attacks on the U.S. fleet in the Lingayen Gulf: “Between October 25, 1944, when the Kamikaze pilots made their first successful attack, and January 25, 1945, we estimated that our suicide pilots inflicted from light to severe damage to at least fifty American vessels of all types. These included six large aircraft carriers, four of which were identified as the Intrepid, Franklin, Essex and Lexington; the two small aircraft carriers Belleau Wood and Independence; and the escort carrier St. Lo. It was impossible at the time, of course, to determine specifically the names of these carriers our planes had struck such as the Santee, Suwannee, etc., until corroboration could be received through American reports. Confirmation by our escorting Zero fighters was at best a questionable affair, because of the speed of the attacks, the fierce fighter and anti-aircraft defenses, and the abort period over the target area.”[16]

January 18, 1945, the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War made official government policy of, Admiral Ohnishi’s Special Attack Corps. “The Council decided to ‘concentrate on converting all armament production to special attack weapons of a few major types.’ The available weapons systems were reduced to a suicide arsenal that included special submarines of the Koryu and Kaiyu class, high-speed small boats of the Shinyo class which exploded upon contact with enemy ships, and the Kaiten human torpedo. The army’s contribution was a human bomb: a soldier wrapped in explosives who hurled himself against an enemy tank, blowing it and himself to bits. A military psychology insensitive to human life, to the individual’s right to survive, conceived the Special Attack idea. The same mentality underlay the policy of requiring Japanese soldiers taken prisoner, even if they managed to return to friendly lines, to commit suicide.”[17]

Okinawa

Special Attack Corps operations were unleashed against the 5th Fleet supporting the marines and GIs ashore. 355 Kikusuis swarmed 5th Fleet, in addition to conventional dive-bombing and torpedo attacks. In two days, April 6 and 7, 19 ships were damaged.

Again the optimum targets were the carriers, especially with disabling same by crashing into the elevators. A flattop unable to utilize its air complement was little better than a target. Other targets of opportunity were support vessels, supply ships, troop transports, . . . On April 1, a Kamikaze struck the transport Alpine, killing 16 and wounding 27. Another transport, Achernar, was both bombed and crashed by a Kamikaze, leaving 8 killed and 41 wounded.[18]

Undamaged cargos were unloaded leaving both ships to retire from the scene for repairs.

On April 3, the escort carrier, Wake Island, faced off with five planes coming in from her starboard quarter. Two diving for her missed, splashing near the flattop. The second, though, exploded, tearing a hole 18 by 45 feet into Wake Island’s hull. It was back to Guam for repairs.

To shield 5th Fleet from attack and act as an early warning system, destroyers were assigned, along the lines of Britain’s radar stations that acted as that early warning system for RAF squadrons during the battle of Britain. Yet despite the mobility of the American system, these picket destroyers and the bluejackets who manned them must be remembered for their courage and heroism for their part in the Plight of the Pickets.

Plight of the Pickets

March 24, 1945, USS Mannert L. Abele (DD-733), an Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer, began the campaign with the preliminary bombardments of Okinawa. By April 12, DD-733 was on picket duty, Station No. 4, some 70 miles northwest of Okinawa.

At 1445 hours, a trio of dive-bombers popped out of the clouds. Pilots pushed over into their death dives. Ablele’s gunners threw up a cloud of A.A. Two of the intruders were flamed. The third, too, was hit, then plunged into the sea.

Then, three more, this time Zeros. Two were quickly splashed. The third Zeke, bracketed by 40 mm and 20 mm and the 5-inch main batteries, was soon hit. Pieces flew back into the slipstream. Flames and black smoke marked the pilot’s path to imperial heaven.

But the gunners could not prevent the Zero’s appointed rendezvous and it crashed into the starboard side, just aft of Abele’s no. 2 stack. The Zero’s bomb pierced the main deck, exploded in the after engine room, rupturing the can’s keel, wrecking the propeller shaft, killing nine men.

Then, in quick succession, skimming the sea, sped a Baka Bomb. The piloted cigar tube was closing the can at upwards of 500 mph. Gunners furiously targeted the missile, but to no avail, as it knifed into the forward fireroom, killing and wounding bluejackets, violently shaking the ship and breaking the keel yet again.

MXY7-KI Ohka or Oka, meaning “Cherry Blossom.” Many Allied military personnel preferred “Baka” meaning idiot or dumb. A manned rocket which could hit upwards of 500 mph, designed to crash into enemy ships. Usually carried by a mother plane to its assigned launch point. Such a plane was the Mitsubishi G4M medium bomber, known to the Allies as the “Betty.” As a bomber, the twin-engine Betty had a great range, some 2,262 miles. But this came at the expense of armor for the crew and fuel tanks.

The stricken DD began to settle. Commander A.E. Parker ordered the crew to the boats. Eighty-two of his crew were dead, 32 more were wounded. All together 336 were rescued.

The Abele broke in two, then disappeared beneath the waves.

* * * * *

April 16, 1945: Radar Picket Station No. 1, off Okinawa

On duty here was USS Laffey (DD-724), another Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer. Skipper was Commander Frederick J. Becton. Laffey will go down in American history as one of the most damaged of warships, certainly of destroyers and, . . . fortunately, Becton and many of his crew will live to tell the tale.

In concert with DD-724 was a pair of Landing Craft Support vessels, LCS-51 and LCS-116. These “were adaptations of Landing Craft Infantry armed with .50-caliber, 20 mm and 40 mm guns. Slow—a top speed of 16 knots—shallow-bottomed and squat—160 feet long, with a 23-foot beam—the ungainly LCS’s chief merit was versatility.

“Two high-capacity pumps enabled the gunboat to double as a fireboat. Young LCS skippers like the 51’s Lieutenant Howell D. Chickering and the 116’s Lieutenant A.J. Wierzbicki had few illusions about their purpose. After suicide attacks, they would be dousing fires, removing casualties, and recovering survivors.”[19]

0827, the radar operator’s screen was aglow with fifty enemy aircraft, all approaching from the north. The stage was now set for the next eighty minutes, the battle for survival began.

Laffey’s fire direction officer urged the area’s combat air patrol to steer clear of the can’s anti-aircraft fire.

On closing the Laffey, Kamikazes came in from every point on the compass. The aim was to not only split the gunnery, but overwhelm it. Indeed, officers aboard Laffey will note 22 attacks.

The battle began when four Aichi D3A Val dive-bombers targeted Laffey. Two bore in from the starboard bow.

Captain Becton barked, “Hard left rudder!” The DD, at flank speed, came round hard.

Gunners splashed the Vals coming in to starboard. A third Val, wave-hopping, was hit by 20 mm fire. Its fixed landing gear caught a wave, then pitched into the sea. The fourth Val, off the port quarter, was hit and splashed by gunners from Laffey and LCS-51.

Four up, four down. But the action continued. A pair of speedier Yokosuka D4 Judy dive-bombers came in, one to port, the other to starboard. Gunners blasted the threat to starboard. The second Judy roared in from the port quarter, strafing, was hit by 40 mm and 20 mm fire, then crashed into the sea. The bomb it was carrying detonated, spraying the port side with fragments, wounding several gunners and, knocked out the SG surface search/low-altitude aircraft and fire control radar antenna, as well as a radio antenna.[20]

Then in came another Val from the port beam. Every 5-inch gun opened up, with lesser calibers joining in the symphony of gunfire. The onrushing pilot brushed the 5-inch turret aft, killing one of the gun crew, then plunged into the sea. Then came another Judy to starboard. 40 mm and 20 mm set the gas tank alight, turning the Yokosuka into a torch, then it crashed into the sea.

A ninth attacker, another Judy, from the port beam. 40 mm and 20 mm gunners hit the plane repeatedly, to no avail as the intruder struck the Laffey, taking out a whaleboat before piling into a pair of 20 mm gun mounts and starting a roaring fire abaft the second stack. Two 40 mm mounts atop the deck house were now besieged by flames. Ready rounds began to explode. Sailors rushed to toss unexploded rounds overboard. This attack severed communications with the forward engine room.

The ship that would not die, USS Laffey, DD-724, circa 1945, probably before the savage Kamikaze attack on April 16, 1945 off Okinawa.

Two minutes later, another Val, skimming the sea from astern, raking the deck with machine gun fire, slammed into the DD and exploded. A river of flaming gasoline spread across the fantail. A second Val dropped its bomb, which hit abaft the after 5-inch gun turret, to which the plane struck the turret, killing six men inside.

Then another plane dropped a bomb which struck Laffey astern, severing the hydraulic lines to the steering gear, jamming her rudder to port, leaving DD-724 circling.

The tortured can by now had lost two 40 mm and five 20 mm mounts; a vulnerability compounded by the fires being fought by her crew. And, there was still the air threat.

Two more attackers made a beeline for the stricken can. Every gun that could opened up. From the port quarter, the first plane, a Val, crashed into the after deckhouse, spilling gasoline and starting another fire; followed by a Judy which crashed into the same spot, killing four men. The after deckhouse was now an inferno.

Then a fighter plane, an Oscar, came screaming in, aiming at the forecastle. On its tail, pilot braving the ship’s A.A., was a Corsair, its guns chattering. The intruder narrowly cleared the bridge, taking out the portside yardarm as he crashed into the sea. The pursing Corsair collided with the air-search radar antenna, damaging the plane. The pilot was able to gain altitude, then bailed out. He was later picked up by LCS-51.[21]

Tom McCarthy, a signalman, seeing that the Oscar had taken out the yardarm, grabbed another battle ensign. He affixed same to the mast.

A more detailed combat air patrol arrived. Corsairs from Intrepid (CV-11) and Hellcats from the light carrier San Jacinto (CVL-30). But the battle was over.

Laffey’s situation was extremely critical. Flooded compartments aft left her low astern in the water. Fires aft still raged and, her steering gear was jammed. Air search and surface search radars were destroyed. And with much of the electrical power having been knocked out, many of her guns were on manual. Surprisingly though she was still afloat after taking six Kamikazes and four bombs. Then again, maybe not so surprisingly. For there was her valiant crew, who had leaped to their ship’s defense.

Laffey was accorded a Presidential Unit Citation. Commander Frederick Julian Becton, a Navy Cross. Lieutenant Howell D. Chickering, c.o. of LCS-51, a Navy Cross. Ensign Robert Clarence Thomsen, a posthumous Navy Cross. Other crewmen on the Laffey: six Silver Stars, 18 Bronze Stars and a Navy Letter of Commendation.

And the Laffey? She would be repaired and returned to the fleet. She would later serve during the Korean War and, be accorded two more Battle Stars.

DD-724, the damaged USS Laffey, after the Kamikaze attack on April 16, 1945.

* * * * *

Postscript

In Volume XIV of his epic rendition of the naval war in World War II, Samuel Eliot Morison offered a pertinent analysis of the events at Okinawa:

“Thus, as the war against japan drew to its close, Okinawa became a giant air and naval base which was destined to play a major role in the Cold War that followed the war with Japan. For it we paid a heavy price. Thirty-two naval ships and craft had been sunk, mostly by Kamikaze attack and 368 ships and craft had been damaged. The fleet lost 763 aircraft. Over 4,900 sailors were killed or went missing in action, and an additional 4,824 were wounded. This was by far the heaviest loss incurred in any naval campaign in the war. Tenth Army also suffered heavy casualties: 7,613 killed or missing in cation, 31,807 wounded and more than 26,000 non-battle casualties.”[22]

The final word of the story belongs to Winston Churchill, who observed in a communication to President Harry Truman, June 12, 1945: “The strength of willpower, devotion and technical resources applied by the United States to this task, joined with the death struggle of the enemy, . . . places this battle among the most intense and famous in military history. . . . We make our salute to all your troops and their commanders engaged.”[23]

Endnotes

[1] Kikusui or Floating Chrysanthemums was the name of an operation conducted by the Japanese against the U.S. fleet supporting the marines and GIs at Okinawa, April 6 to June 22, 1945. See page 142, Chapter 16, “Homeland Special Attack Units, April 1945-June 1945,” The Devine Wind, by Captain Rikihei Inoguchi and Commander Tadashi Nakajima, Former Imperial Japanese Navy with Roger Pineau.

[2] See page VI, “Forward,” The Devine Wind, by Captain Rikihei Inoguchi and Commander Tadashi Nakajima, Former Imperial Japanese Navy with Roger Pineau.

[3] Three costliest battles in American history: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918; Battle of the Bulge, 1944 and Okinawa, 1945.

[4] See page 1, “Under-Sea Kamikaze,” by Richard O’Neill, War Monthly, Issue No. 9, December 1974. See, too, pages 40 and 41, A History of Japan, by Richard Storry, who highlights 1274 and 1281. With the prior attempt, “The armada began by attacking two islands, Tsushima and Ikim that lie between Kyushu and Korea. The small garrisons on these islands fought to the death—a tradition observed in 1945 on other islands guarding the approaches to Japan. The Mongols then made a landing in Kyushu and a stubborn battle took place. However, a severe storm threatened the ships as they lay offshore; and the Mongol force embarked and withdrew. The elements were to intervene even more effectively on the side of Japan in 1281. On this occasion, after landing in Kyushu, the Mongols fought, in the small bridgehead they had seized, a campaign that lasted without interruption for fifty-three days. Then on 14 August 1281 a typhoon descended upon the Mongol fleet and virtually wiped it out. This typhoon the Japanese had every right to regard as providential. In shrines and temples throughout the land prayers had been offered for deliverance from the invaders. The typhoon, then, was called “The Devine Wind,” the Japanese name for which is Kamikaze.

Also, per Thomas Cutler, The Battle of Leyte Gulf, pages 265 and 266, offers the god of wind. “Years of dissention and internal wars had weakened the Japanese and they were in no shape to repel the Mongol invaders. Having resigned themselves to either death or slavery, the fortuitous appearances of the typhoons were hailed as an intervention by Ise, the wind god. A legend was born that would carry over the centuries, strengthening the Japanese belief that they were a divinely protected people, convincing them that their destiny had been ordained by the gods and that they had been saved by what they called the “devine wind”—Kamikaze in Japanese.”

[5] See page 27, Chapter Two, “Organizing for Death,” The Kamikazes, by Edwin P. Hoyt.

[6] See page 53, Edwin P. Hoyt.

[7] See page 25, “Marianas Aftermath,” The Devine Wind, by Captain Rikihei Inoguchi and Commander Tadashi Nakajima, Former Imperial Japanese Navy with Roger Pineau.

[8] See pages 6 and 7, Captain Rikihei Inoguchi and Commander Tadashi Nakajima, Former Imperial Japanese Navy with Roger Pineau.

[9] See pages 11 and 12, Captain Rikihei Inoguchi and Commander Tadashi Nakajima, Former Imperial Japanese Navy, with Roger Pineau.

Shikishima—Poetic name of Japan; Yamato—Ancient name of Japan; Asahi—Morning sun and, Yamazakura—Cherry blossoms.

[10] See pages 78 and 79, Chapter Seven, “A-Operation Day,” The Kamikazes, by Edwin P. Hoyt.

[11] The five damaged carriers were as followed: Santee, Suwanee, Kitkun Bay, Kalinin Bay, and White Plains. See pages 306 and 307, Chapter Nineteen, “The Lost Chance,” The Battle of Leyte Gulf, by Edwin P. Hoyt.

[12] See page 77, Chapter 6, “The Suicide Manual,” Kamikaze: Japan’s Suicide Gods, by Albert Axell and Hideaki Kase.

[13] See pages 80 and 81, “Page 37: Chapter 6, ‘Suicide Manual,’” Albert Axell and Hideaki Kase.

[14] See page 81, “Page 39: Chapter 6, ‘Suicide Manual,’” Albert Axell and Hideaki Kase.

[15] See page 8, Chapter 1, “Operation Heaven Number One,” Tennozan, by George Feifer.

[16] See page 250, Chapter 24, “The Kamikaze Suicidal Attacks,” ZERO!, by Masatake Okumiya and Jiro Horikashi with Martin Caiden.

[17] See pages 183 and 184, Chapter 9, “The Horrors of War,” The Pacific War, by Saburo Ienaga.

[18] The attention paid to transport vessels made perfect logistical sense. No ability to resupply the landing forces means no successful campaign ashore. Historical parallel here was the night of August 8-9, 1942, when Admiral Guichi Mikawa surprised and defeated the American naval support forces at Savo Island, sinking three American and one Australian heavy cruisers. But Mikawa, concerned with being caught by American aircraft the following morning as he withdrew up the Solomon Islands chain, did not attack the American transports supporting the Marines ashore on Guadalcanal.

[19] See page 7, “Battered Beyond Belief: The Story of the Destroyer Laffey,” by David Sears, www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/06/07/…

[20] See page 4, “H-045-1: The Ship That Wouldn’t Die(2)—USS Laffey (DD-724) 16 April 1945,” www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/about…

[21] The presence of an Oscar fighter, which is an Army plane, perhaps shows Army-Navy cooperation in this attack.

[22] See page 282, Chapter XVIII, “Okinawa Secured, June-September 1945,” Victory in the Pacific, Volume XIV, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, by Samuel Eliot Morison.

[23] See pace 282, Samuel Eliot Morison. Quote originally published in the New Time Times, June 23, 1945.

Bibliography

Axell, Albert and Kase, Hideaki, Kamikaze: Japan’s Suicide Gods, Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh and London, Great Britain, 2002.

Cutler, Thomas J., The Battle of Leyte Gulf, 23-26 October 1944, HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., New York, NY., 1994.

Feifer, George, Tennozan: The Battle of Okinawa and the Atomic Bomb, Ticknor & Fields, New York, NY., 1992.

“H-045-1: The Ship That Wouldn’t Die (2)—USS Laffey (DD-724), 16 April 1945,” www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/about …

Hoyt, Edwin P., Closing the Circle: War in the Pacific, 1945, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, Inc., New York, NY., 1982.

Hoyt, Edwin P., The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Death Knell of the Japanese Fleet, Weybright and Talley, New York, NY, 1971.

Hoyt, Edwin P., The Kamikazes: Suicide Squadrons of World War II, Burford Books, Inc., Short Hills, New Jersey, 1983.

Ienaga, Saburo, The Pacific War, Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, 1978.

Inoguchi, Captain Rikihei and Nakajima, Commander Tadashi, Former Imperial Japanese Navy with Roger Pineau, The Devine Wind, Bantam Books, Inc., New York, NY., 1978. Originally published by the United States Naval Institute, 1958.

Ireland, Bernard, with Gerrard, Howard, Leyte Gulf 1944: The World’s Greatest Sea Battle, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2006.

Mikesh, Robert C., ZERO, a Warbird History, Motorbooks International Books & Wholesalers, Osceola, Wisconsin, 1994. Forward to this selection was written by legendary Zero ace, Saburo Sakai.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, Victory in the Pacific, Volume XIV, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Castle Books, Edison, New Jersey, 2001. Originally published 1960.

Munson, Kenneth, Aircraft of World War II, Doubleday & Company, Inc., printed by Crampton & Sons, Ltd., Sawston, Cambridge, Great Britain, 1968. Originally published by Ian Allen, 1962.

Okumiya, Masatake and Horikoshi, Jiro, with Caiden, Martin, ZERO! The Story of Japan’s Air War in the Pacific: 1941-1945, Ballantine Books, Inc., New York, NY., 1956.

O’Neill, Richard, “Under-Sea kamikaze,” War Monthly, Issue No. 9, Marshall Cavandish, Ltd., London, England, December 1974.

Parkin, Robert Sinclair, Blood on the Sea: American Destroyers Lost in World War II, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2001.

Sears, David, World War II Magazine, “Battered Beyond Belief: The Story of the destroyer Laffey,” Navy Times, June 7, 2019, www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/06/07/…

Storry, Richard, A History of Modern Japan, Penguin Books, Ltd., Middlesex, England, 1975. Originally published, 1960.

Whitley, M.J., Destroyers of World War II: An International Encyclopedia, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2000. First published 1988, Arms & Armour Press, London.