Ask the Flight Surgeon / By CPT Nathan H. Kwan, M.D. & MAJ Titus J. Rund, O.D.: The topic for this issue is Obstructive Sleep Apnea, an all too common condition with potential for negative impact on flight safety.

The quality of Soldiers’ sleep has a direct bearing on readiness, said Col. Vincent Mysliwiec. Shown here, paratroopers ride in a C-17 from Alaska to their jump site in Australia, a duration of 17 hours that left many trying to get some pre-jump rest on the aircraft. (Photo Credit: David Vergun)

Background

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a condition where breathing is temporarily, but repeatedly, interrupted by complete or partial obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. This can often lead to decreased oxygenation of the blood, disrupted sleep and excessive daytime sleepiness. OSA affects as much as 3-5% of the general U.S. adult population. In aviation, OSA can contribute to lapses in attention, concentration, and executive decision making. Thus, undiagnosed or untreated OSA may result in mishaps that injure or kill aircrew and may degrade the mission effectiveness of aviation units.

OSA is a disqualifying condition that requires a waiver to continue flight duties. In order to be considered for a waiver, the aircrew member must be seen by a Sleep or Pulmonary Medicine specialist. Additionally, a test called a polysomnogram (PSG), or sleep test, must be performed overnight at a military treatment facility or at an American Academy of Sleep Medicine accredited sleep facility in order to confirm the diagnosis. One of the test measurements is called the Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI). Apneas are temporary stoppages of breathing. The AHI quantifies the severity of OSA experienced during sleep. A normal AHI is less than 5 events per hour. An AHI of 5-15 indicates mild OSA, 15-30 is moderate OSA, and 30+ is severe OSA.

OSA is a disqualifying condition that requires a waiver to continue flight duties. In order to be considered for a waiver, the aircrew member must be seen by a Sleep or Pulmonary Medicine specialist. Additionally, a test called a polysomnogram (PSG), or sleep test, must be performed overnight at a military treatment facility or at an American Academy of Sleep Medicine accredited sleep facility in order to confirm the diagnosis. One of the test measurements is called the Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI). Apneas are temporary stoppages of breathing. The AHI quantifies the severity of OSA experienced during sleep. A normal AHI is less than 5 events per hour. An AHI of 5-15 indicates mild OSA, 15-30 is moderate OSA, and 30+ is severe OSA.

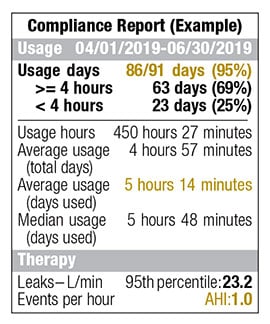

Although there are different treatments available like weight loss, surgery, and oral appliances, this article will focus on positive airway pressure (PAP) machines used during hours of sleep. PAP machines work by pushing air through the airway passage at a pressure high enough to prevent apnea events. These machines also capture data that is used to monitor the effectiveness of therapy and produce a compliance report like the example shown.

Information Required for Initial Waiver

The revised Aeromedical Policy Letter (APL) for OSA was published in June 2019. To be considered for an initial waiver, a 30 day PAP compliance report must be submitted that shows usage days greater than 90%, average usage (days used) greater than 5 hours, and an AHI less than 5. However, an AHI of 5-10 may be allowed if the aircrew member does not have aeromedically significant symptoms such as excessive daytime sleepiness, morning headache and/or difficulty concentrating during the day. These requirements are more stringent than the previous policy and are highlighted in yellow in the example report.

Annual Waiver Requirements & Follow-Up

If a PAP device is used to treat OSA in an aircrew member who has already been granted a waiver, a 90 day PAP compliance report must be submitted with each annual flight physical and must meet the same requirements as the initial waiver – usage days greater than 90%, average usage (days used) greater than 5 hours, and AHI less than 5. Again, an AHI of 5-10 may be allowed in the absence of aeromedically significant symptoms.

If there are periods in which usage days do not exceed 90%, the aircrew member should not perform any flight duties during these non-compliant periods. The aircrew member may resume flight duties once compliance is reestablished and they are well rested.

The bottom line is that PAP devices are first line treatments for OSA if compliance is maintained. Fight fatigue and fly safe!

Army safe is Army strong.

Question for the Flight Surgeon?

If you have a question you would like addressed, email it to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.; we’ll try to address it in the future. See your unit flight surgeon for your personal health issues.

The views and opinions offered are those of the author and researchers and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position unless otherwise stated.

CPT (Dr.) Nathan H. Kwan is a resident physician at the U.S. Army School of Aviation Medicine, Fort Rucker, AL. Dr. Kwan is completing his training in aerospace medicine; and MAJ (Dr.) Titus J. Rund, an Aerospace Medicine Specialist at the U.S. Army Aeromedical Activity, Ft. Rucker supervised the writing of this article.