By COL. Jack K. Norris, Commandant, USAPHS: Everyone associated with Army aviation is familiar with its birth during World War II as a means of providing observation for the adjustment of artillery. Pilot observer teams flew light fixed wing aircraft adjusting artillery fire both in the European and Pacific theatres. Hazards from enemy weapons were normally limited to small arms fire which gave the observation team relative freedom of the air.

The normal practice was to fly a racetrack, or figure eight type pattern which allowed constant surveillance of the target area. With the development of more sophisticated anti-aircraft weapons systems, previously used flight techniques are no longer feasible.

Warfare has changed in many ways since World War II, however, the requirement for aerial adjustment of artillery remains. Thus, new procedures are needed which will keep aircraft losses at acceptable levels.

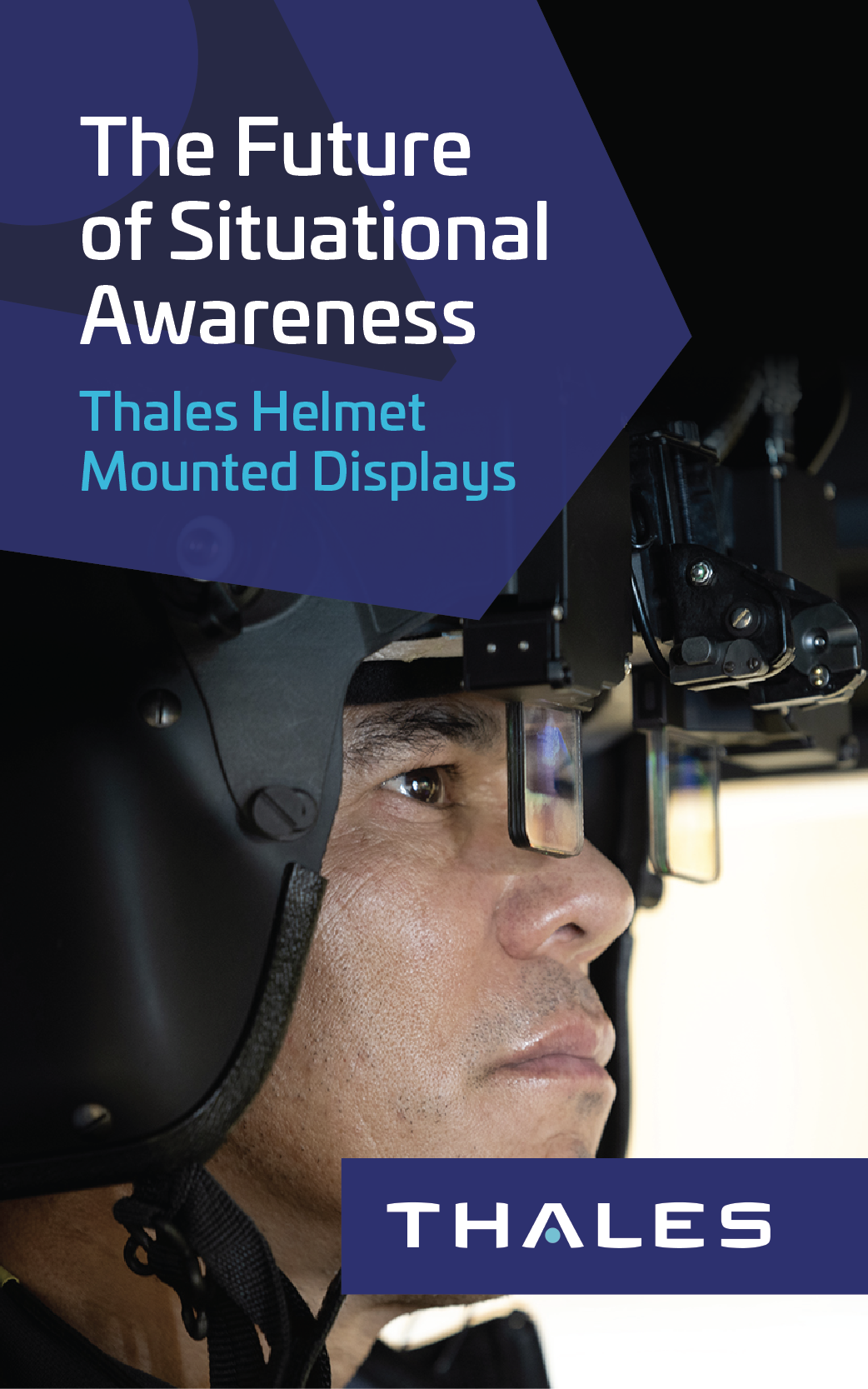

An Army OH-23C Raven, made by Hiller Aircraft Corp., in nap-of-the-earth flight.

To enhance survivability on the modern battlefield the tactics phase of the Officers’ Primary Utility Transport-Observation Rotary Wing Aviators Course, conducted by the U.S. Army Primary Helicopter School at Camp Wolters, Texas, and Fort Sill, Oklahoma, was initiated. This program included all nap-of-the-earth flight techniques.

During the final phase at Fort Sill, thirty-three hours are devoted to adjustment of artillery fire. Twelve of these hours are spent in the classroom preparing the student for the remaining twenty-one hours which are devoted to firing service practice.

Standard methods are used during service practice in adjusting artillery fire; volleys are successively adjusted to the gun – target line and range changes are made until effective fire is brought to bear on the target. Flight techniques have changed completely.

The old racetrack pattern has been replaced with a nap-of-the-earth flight technique. The flight path and altitude vary with the mission, terrain, situation and weather; however, the objective is to limit, to the absolute minimum, the time the aircraft is exposed to the enemy. The aviator must remain concealed by making full use of cover and concealment.

Three ‘Service Practices’

There are three service practices. The first, a ground service practice, allows the student to put the procedures he has learned in the classroom into practice. He develops his ability in target identification, range estimation and the adjustment of fire.

The second, an aerial service practice, is flown by an instructor pilot. The student adjusts fire while the pilot demonstrates various flight techniques which include selecting more than one pop-up point, timing flight to arrive at the pop-up point just as the splash is received; selecting flight routes that will allow for continuous radio communication with FDC and ways and means of remaining concealed with maximum safety of flight.

The third and last is a repeat of the second service practice, except that now the student must do all the work, fly, adjust and communicate. He is graded by the artillery instructor on the ground for the adjustment of the mission while the flight instructor grades his flight techniques.

The area selected for these service practices is the rolling terrain of the East Range at Fort Sill rather than the hilly to mountainous type found in the West Range. This terrain is demanding of the aviator requiring the exercise of good judgment and planning to remain concealed. Each draw, fold and tree has to be considered in selecting flight route.

A Typical Mission

A Typical Mission

Let’s take a quick look at a typical mission. The target has been identified and the fire request has been sent to FDC. The student is weaving his way down a dry creek bed, maintaining 20 to 30 miles per hour airspeed. The slow airspeed provides the aviator with maximum maneuverability allowing him to take advantage of the terrain available.

The radio crackles “Tactics One, Two, this is Bongo – Battery is ready.” The aviator is not in a good position for pull-up and observation; he mashes the transmitter button – “Bongo, this is Tactics One Two, wait.” He turns around a clump of trees on his left so that now the target area is to his front left. “Bongo – this is Tactics One Two, Fire.” “This is Bongo, on the way.”

By SOP the FDC furnishes the projectile’s time of flight – in this instance at twenty-two seconds. The student checks his time, increases his airspeed so that seventeen seconds later, at 70 miles per hour, he begins his pull-up. As he clears the terrain he spots the target just as he receives the “splash.” He mentally senses the rounds and begins his rapid descent down to safety. He sends his adjustment and goes into hiding again, only this time selecting a new flight path and planning ahead to a new pull-up point.

This series of events continues until the target is neutralized and the mission is ended. Observation has been excellent, exposure time approximately ten seconds per adjustment and always in a different place.

Why Teach Observation

Why teach aviators these obvious duties of observers? Let’s answer that question with a question. How many aerial observers had to be trained by the aviator on combat missions in Korea? Answer: Unknown – but a good share of the observers assigned to the air sections in Korea had never been in the air before. The aviator is responsible for the overall mission and must have the knowledge and know-how or the mission is in jeopardy.

Most old artillery observers will doubt the validity of this technique; however, observers at Fort Sill have been amazed at the ability of students to master the technique. There is no denying that this is much more difficult than adjusting from a ground OP; however, with proficiency at nap-of-the-earth flight and adjustment skill, it can be done.

With the marriage of new flight techniques to old established methods of adjusting artillery fire, one of the problems of survival on the battlefield of today has at least been partially solved.

Army aviation must meet each new challenge and provide the commander of today with the support he has rightly come to expect.

COL Jack K. Norris was the commandant of the U.S. Army Primary Helicopter School at Camp Wolters, TX, and Fort Sill, OK, when this article was published in the December, 1962 issue of ARMY AVIATION.