By LTC Paynee O. Lysne, Ret.: When the Second U.S. Army Corps went to England in 1942, it presumably went with a full complement of L-4 Cub planes and pilots, two pilots and planes per Field Artillery Battalion. These pilots were presumably and probably graduates of Class One or Two at Ft. Sill, OK.

Before the invasion of North Africa, or shortly thereafter, someone discovered that there were not enough pilots and airplanes to fill the authorized TO&E for the artillery. Sometime in December, 1942, I was sitting at the Company CO’s desk, G Company, 591st Engineer Boat Regiment, and read a flyer that in essence said “We need pilots to fly L-4 type aircraft.” I didn’t know an L-4 from a B-17, but I did have my private pilot’s license which I received through the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) during college in 1940-1941.

On 3 February 1943, HQ Fifth Army issued orders to nine officers and seven enlisted men in various units throughout North Africa, placing them on Detached Service to the Fifth Army Air Op School at Sidi-Bel-Abbes, Algeria, North Africa. Sidi-Bel-Abbes was then the home of the French Foreign Legion. My Company Commander, CPT William G. Gardner, G Company, 591st Engineer Boat Regiment, took me to the school in his command car. When we were close to the school, we saw those Piper Cubs flying around. The comment from CPT Gardner was, “Do you see those planes, Lysne? They’re just covered with cloth – you’re going to get your ass shot off.” My answer was, “Until then, I’ll be able to sleep between sheets instead of in a damn mud hole.”

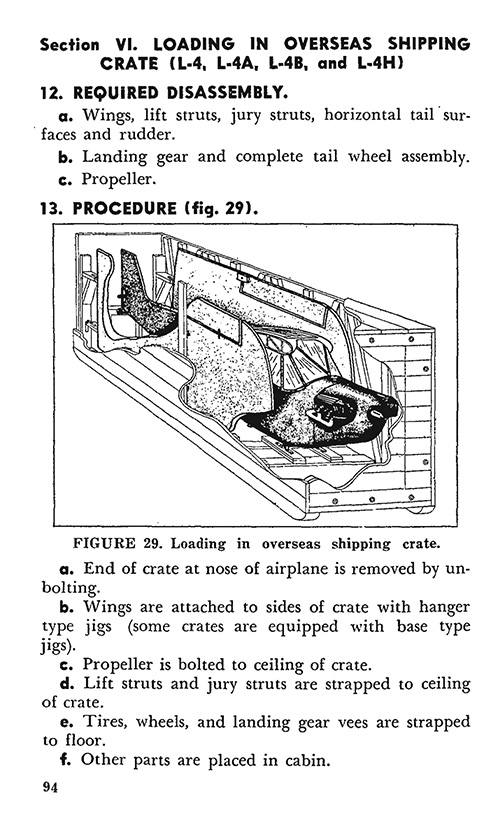

Upon reporting to the school, we reported in “Pinks and Greens” (officers) to LTC John D. Salmon (non-pilot), Commandment, Fifth Army Air Op School. CPT John T. Walker was the Executive Officer, and CPT Delbert Bristol was the Adjutant. Walker was killed as a Major in an airplane crash taking off out of Rome, Italy for return to the States in 1944; Bristol made it to Colonel, and passed away several years ago. After reporting I was told along with two others by a tough-looking Sergeant, “Do you see that large box? Well, in that box is an airplane, which you’ll take out carefully. Assemble it by the book, and tomorrow, you’ll fly it. And that box will be your home for as long as you’re here in school. Make yourselves comfortable, and get to work.” We did.

The flight instructors were Lieutenants Kaufman, Strok, Hall, Hendrix, Oswalt, Albert, Ely, Hartsfield, and Robertson. The students were Lieutenants Eifrig, Kleinsasser, Board, Johnson, Righter, Weil, Clark, Feinburg, Bollard, Staggers, Dale, Mack, myself, and Sergeants Herbert, Lynn, Huttlin, Sabadini, Stegall, Moody, Jellison, Atkinson, Kietzman, Cassel, McCullum, and Sheppard. Most of us received an average of 70 hours of contour flying, road landings, chasing goats, sheep, Arabs, etc. – very similar to the training program at Ft. Sill, with one exception: shooting touch and gos on the tops of Trailways busses as they were going down the highway west of Lawton, OK.

When the bus company decided to wash the busses, they found many tire tracks on the tops. The facilities at the airfield were adequate: a large sod field with no obstructions, a couple of hangars, and one or two other buildings. The aircraft crates were converted into cozy billets. There was considerable air activity in the vicinity – low-level training in B-25s and B-26s, C-47s towing and releasing gliders, and low-level practice runs by fighter planes.

At some time during our training program, the school was moved to an airfield near the town of Mascara, Algeria. This area was noted for its vineyards and wines. The war put a stop to the wine activities. The billets for the officers were in a winery with 900 gallon vats all around – not too good for the would-be pilots, but we were saved as the vats had drowned rats floating around in them. One of the prerequisites to graduation was “don’t break a propeller”; if you did, you were automatically terminated from the school, since there was a real shortage of props in the North African theater of operations.

Upon graduation, we were sent to various units throughout the theater that were short pilots; almost all went to Field Artillery units. I was sent to the HQ, Fifth Army at Oujda, Morocco as Fifth Army Air Courier Officer, attached to the Fifth Army Artillery Section under General Thomas E. Lewis. From North Africa, some of the pilots went on to Sicily, others went on to Italy.

Lieutenants Robert S. Feinberg and Ross Fleming were launched off an LST PSP (Pierced Steel Planking) runway during the invasion of Italy at Salerno. Their job was to recon, observe, and adjust artillery on the enemy. This was a one way trip, as you could not come back and land on the LST. When the pilots ran low on gas, they had to land and refuel from any source available, usually a truck or tank with five or ten gallons of gas, and then continue on their mission.

There was one pilot, PFC Charles R. Holladay, that prior to the war was a test pilot for Aeronca. He was a ground pounder in the VI Corps, and was picked up by the Corps Artillery Aviation Officer to come and fly with him to fill a vacancy. He was an expert and knew all the tricks, as he was one of the civilian demo pilots during the Louisiana Maneuvers.

All graduates from the Fifth Army Air Op School continued to fly combat missions. But someone opened a can of worms by “discovering” that those pilots which were trained in North Africa were not properly rated “Liaison Pilots” – in other words, they hadn’t been rated by the Army Air Corps Instructor Pilots at the Primary Flight School at Pittsburg, KS. From there, the students went on to Ft. Sill for advanced training, graduation, and rated Liaison Pilots. In February 1944, HQ Fifth Army published Special Order #33, which relieved 26 officers and enlisted men from duty in the Mediterranean theater of operations and assigned them to Ft. Sill for the purpose of undergoing further training with a view to being rated Liaison Pilots.

What a big deal – we were all combat qualified, had many hours of combat flying, artillery adjustment, fire control, reconnaissance, aerial resupply, float plane operations, and other types of missions. Many of us were up for promotion, but when these orders were published, all recommendations were stopped. I personally had acquired some 500 hours in Africa and Italy. We were authorized to travel by belligerent vessel, commercial transport, Army transport, Navy vessel, and/or rail – in fact, any way we could get there was OK with DA.

Upon arrival at Ft. Sill, we were more or less put in a pool and looked upon as odd balls until the IPs from Pittsburg, KS were sent down to give us our check rides for out rating. My check ride consisted of taking off and climbing to 4,000 feet, my IP eased back on the throttle and said in a loud voice, “FORCED LANDING!” I almost shouted back, “NO S—!” but instead asked if he wanted to land back at Post Field or in one of the fields below. He said one of the fields would be OK. We glided and glided, checked for carb ice, and glided some more.

I set up an approach to a large pasture and on long final, the IP said, “OK, let’s go back to Post Field.” We did, I passed, and my orders rating me a Liaison Pilot were forthcoming. All the others that came back under the same circumstances suffered the same strenuous check ride.

This school was a one time affair, one class only. After this class, the school was closed. Upon graduation, each of us were issued an airplane, a roll of safety wire, a pair of needle-nose wire cutters, and a pocket knife. The knife, we were told, was to carve a propeller in case we broke one. Hopefully I’ve remembered all of this accurately – after all, it’s only been 50 years.