Looking Back, August 2025

By Mark Albertson

Genzai Bakudan

The essence of war is violence. Moderation in war is imbecility. . . Sir John “Jackie” Fisher. See page 55, Chapter 4, “Genzai Bakudan,” by Mark Albertson

* * * * *

“Ahead there was only destruction. A wasteland of shattered buildings, incinerated homes, and scorched earth. A desolate moonscape that became more horrifying as the great steel prow cut lazily through the black waters, pushing though a flotsam of burned and bloated bodies that bobbed like corks in the creamy wake. Occupation troops were set to go ashore. They would face no opposition. Because, you see, the city was dead.”[2]

Sound like an ominous prophecy of Nostradamus?Or perhaps the opening scene from an episode of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone?No. It is the aftermath of Genzai Bakudan, the Atomic Bomb. It is Nagasaki as seen by my father from the bridge of the USS Ottawa (AKA-101), an attack transport loaded with marines. Weeks before, the B-29 Bock’s Car dropped its deadly load, ending the war and proving Major General Leslie Groves correct. For after witnessing the first explosion at Alamogordo, New Mexico, July 16, 1945, the military commander of the Manhattan Project accurately observed, “The war’s over. One or two of these things, and Japan will be finished.”[3] President Truman agreed. On August 2, he authorized the bomb’s use.

* * * * *

The luckless city chosen to usher in the Atomic Age was Hiroshima. Hiroshima was home to an army transport base and food, ordnance and clothing depots. There was also a large railway yard, electrical works, textile mills, oil-storage facilities and a shipbuilding yard. And, according the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, “Hiroshima before the war was the seventh largest city in Japan, with a population of over 340,000, and was the principal administrative and commercial center of the southwestern part of the country. As the headquarters of the Second Army and of the Chugoku Regional Army, it was one of the most important military command stations in Japan, the site of one of the largest military supply depots, and the foremost military shipping point for both troops and supplies. Its shipping activities had virtually ceased by the time of the attack, however, because of sinkings and the mining of the Inland Sea.”[4]

Commander of the 509th Composite Group, Colonel Paul Tibbets, would fly the bomb plane. His crew was as follows:Captain Robert A. Lewis, co-pilot; Major Thomas Ferebee, bombardier; Captain Theodore van Kirk, navigator; Lieutenant Jacob Beser, radar countermeasures officer; Master Sergeant Wyatt A. Dusenbury, flight engineer; Staff Sergeant Joseph S. Stiborik, radar operator; Sergeant George R. Caron, tail gunner; Sergeant Robert R. Shumard, waist gunner; P.F.C. Richard H. Nelson, radio operator. Also aboard was Navy Captain William S. “Deke” Parsons who was in charge of the bomb, and his assistant Morris R. Jeppson.[5]

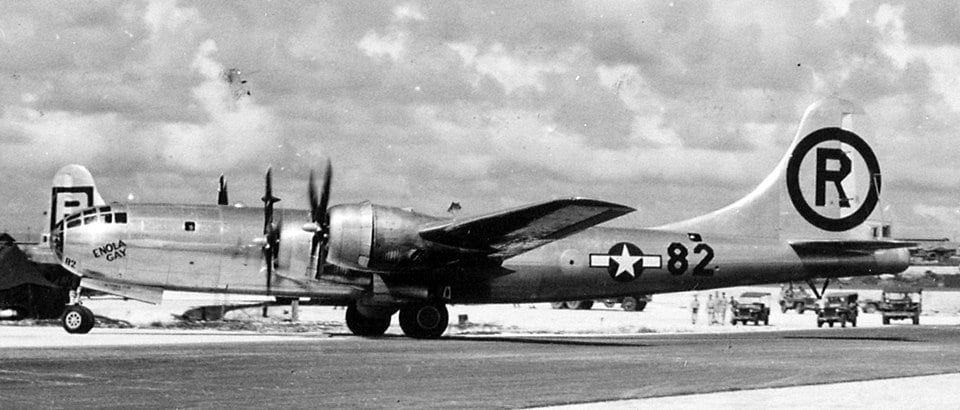

Lieutenant Colonel Paul Tibbets’ bomb plane for Hiroshima, ‘Enola Gay,’ named for his mother.

Group insignias on the three planes making the flight were removed; but, Tibbets had his mother’s name, Enola Gay, painted on the fuselage of his bomber.

The camera plane was to be piloted by Captain George R. Marquardt. While the B-29 armed with the instruments to measure the blast was to be piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney.[6]

The uranium bomb dropped on Hiroshima, August 6, 1945, known as, ‘Little Boy.’

July 16, 1945, Operation:TRINITY at Alamogordo, New Mexico, a plutonium bomb had been expended for the test. But for Hiroshima, the Enola Gay would drop a uranium bomb. “Little Boy” as the bomb was called, was hoisted into the forward bomb bay the night before.

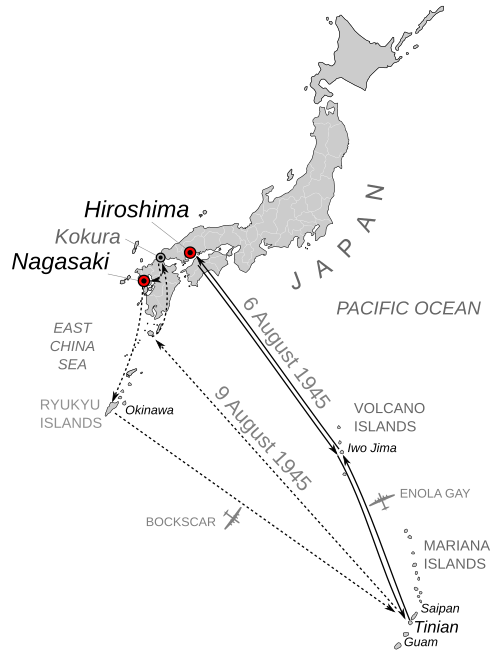

Map showcasing the flight routes of Enola Gay and later Bock’s Car, August 6 and August 9, 1945.

At 0245, August 6, 1945, Enola Gay lifted heavily off the crushed coral runway on Tinian. Marquardt and Sweeney followed at two-minute intervals.

Over the Pacific, Parsons and Jeppson armed the bomb.

Over Iwo Jima, Tibbets began the slow climb to attack altitude. The final decision to bomb the primary or alternate targets rested on information collected by the weather planes flying ahead.[7]

When they reached the Japanese coast, Tibbets’ headphones began to crackle, “2/10 lower and middle lower, and 2/10 at 15,000 feet. ”Visual conditions over Nagasaki, Kokura and Hiroshima were good. So Tibbets turned towards the primary target, Hiroshima.[8]

Tibbets began the bomb run from twenty-five miles out. A twelve miles, he said into his intercom, “It’s yours.”

Major Ferebee took control of the bomber. He lowered his left eye onto the Norden bombsight and focused in. Below, the Ota River snaked its way to a delta, where the tributaries splayed like seven spreading fingers.

Then the Aioi Bridge rolled into the crosshairs. “I got it!” announced the bombardier.

At fifteen minutes and seventeen seconds past eight, the bomb bay doors swung open. Ferebee watched Little Boy tumble out tail first, then nose over towards its target.“Bombs away!”

Less 10,000 pounds, the lumbering Superfort shot up like a cork. Tibbets threw her into a simultaneous sixty-degree dive and 158 degree turn at a speed of 328 miles-per-hour.

Some 31,000 feet below the twisting bomber, 340,000 unsuspecting souls were going about their business.

Forty-three seconds later, a sky-searing flash, like a the popping of a gigantic flashbulb, lit the morning sky and whited out the inside of the fleeing bomber, already eight miles away from ground zero. A shock wave, like a ring spreading outwards, as in a pond, suddenly shot skyward and slammed the bomber, buffeting it as if hit by flak.

Below, the bomb, which had detonated at an altitude of 1,860 feet, had loosed a fireball 110 years in diameter and a heat of 300,000 degrees centigrade. Granite melted. Roof tiles softened and changed color from black to olive or brown. People were vaporized, their outlines burned like negatives into roads, walls and bridges.

The earth-shattering concussion flattened every building but those of the stoutest construction for two miles in any direction from the epicenter. Fires, hundreds of them, sprouted to life simultaneously and raged out of control until 4.7 miles of the city center had been incinerated.

The whirlwind unleashed by the blast tore trees out at the roots and obliterated walls, houses and buildings. Trains, buses and trams were picked up and thrown about like toys.

Minute crumbs of debris, thrown up into the atmosphere by the blast, fell earthward in a black sooty rain that left grease spots on clothes.

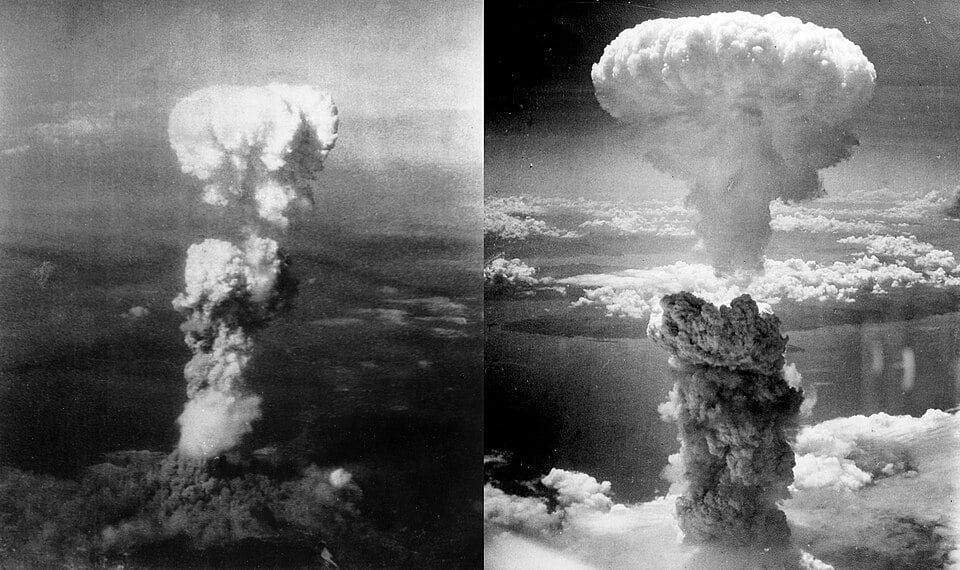

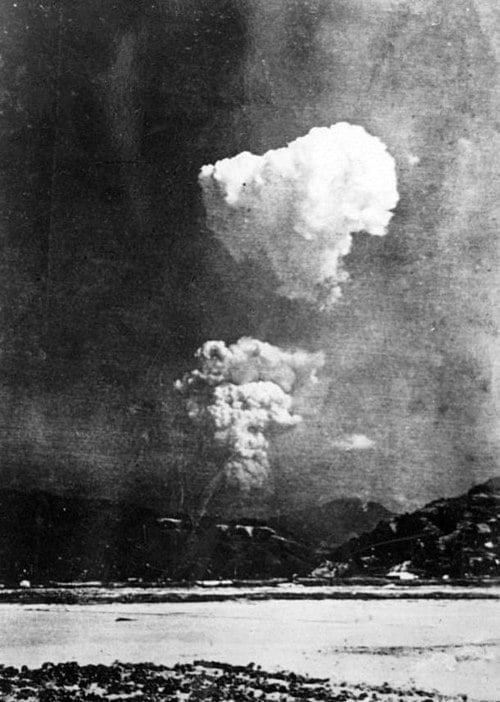

Two stages of the unfolding blast as seen with the rising columns of smoke. The right most photo shows the developing mushroom when at 20,000 feet.

The sinister mushroom cloud climbed to 20,000 feet in sixty seconds. Then the spreading umbrella detached from its stem and floated upwards to 40,000 feet. From his tail gunner’s position, Sergeant Caron could still see the ominous wreath when the Enola Gay was 363 miles away. A tombstone of smoke that marked the demise of Japan’s seventh largest city.

The telltale column of smoke two minutes after the blast.

For better or for worse, Man had entered the Atomic Age.

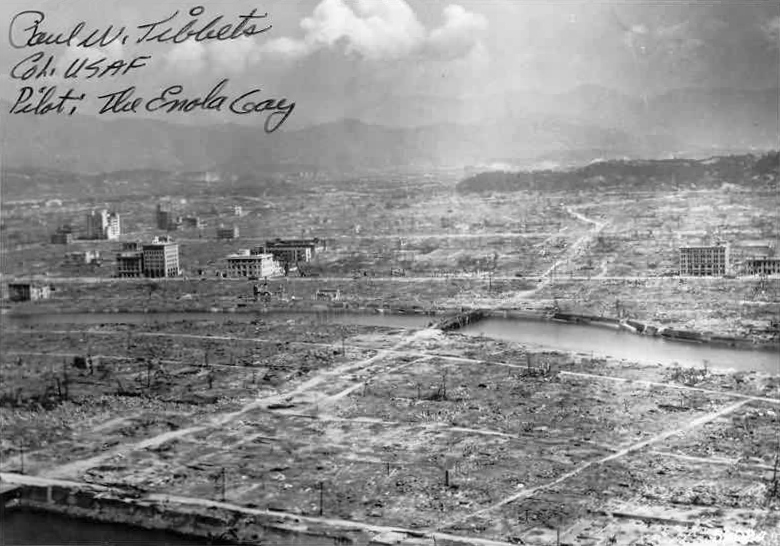

A distant photo shot of Hiroshima following the blast.

Hiroshima after the bomb strike, taken by sailors from the heavy cruiser Tuscaloosa.

* * * * *

Time has a habit of altering viewpoints, opinions and beliefs. Causes for such changes certainly vary. They can range from new information recently brought to light; guilt feelings which prompt second guessing; or, perhaps the previous mode of thinking upon which the opinion or belief was based has suddenly become politically or socially incorrect, and therefore, unacceptable. It is even possible that the new found alternative thinking could be the result of a cocktail of all the above. Perhaps this explains why that after eight decades, a sizable number of Americans are calling into question President Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bombs on Japan. The counterargument is that Japan was a nation against the ropes. That her ill-gotten empire had been wrested from her grasp. That her once magnificent Combined Fleet lay rusting on the bottom of the Pacific. That her industry was in ruins. That food and other essentials were in grievous short supply. Some would go so far as to say that to resort to such a weapon against a nation in the throes of such a disaster was a decision lacking in honor.

“After Pearl Harbor, Japan had no honor,” remarked Harry Truman. If you were at Pearl Harbor that day or heard about the attack on radio or from family and friends, you might have been inclined to agree with the President. For Americans decades removed from the Day of Infamy, it is important for them to remember that the attack on the Pacific Fleet galvanized a pacifist nation seeking to avoid war. That the attack was seen as being in direct contravention to the sense of decency and fair play that pervaded this Nation at the time and which now seems to be in noticeably short supply.

As for other reasons as to why the atomic bombs were dropped, these are based solely on logic. Yet still on the surface it all seemed pointless. For here was a small island nation, her naval power destroyed, industry shattered, without allies and friendless, fighting on against a worldwide coalition.

Any study of wartime Japan cannot be based solely on logic, at least not in the Western sense. Pearl Harbor offers a prime example. While sneak attack had run counter to the basic American tents of decency and fair play, to the Japanese it was an accepted mode of warfare by the Samurai for centuries.

The Samurai spirit lived on in the Japanese soldier. He was certainly one of the most courageous, yet reckless and fanatical of fighting man during the entire Second World War. To him surrender was unacceptable. Only victory brought honor to emperor, country and family. The alternative was death, either in action against the enemy or by his own hand. This was the warrior code of bushido.

Such was the code of the Japanese militarists, who, while in control of the education system, indoctrinated Japanese youth with the martial spirit and love of race. Not too unlike how the Hitler Youth prepared the young of Germany, but with a distinct Oriental flavor:That the spiritual transcends the material.

Just how much disregard the Japanese had for their opponents can be seen in their treatment of enemy combatants they captured. Prisoners of war were viewed with brutal disdain, since they did not die in battle or kill themselves. Chinese POWs were singled out for outrages of the utmost barbarism. Captured Americans, Britons, Australians and New Zealanders fared little better. They were selected for such heartless indignities as starvation, disease, death marches, forced labor, massacres and torture. Some were even killed and eaten by Japanese troops.[9]Bycomparison, Western POWs in the European Theater of War incurred a much lower death rate than unfortunate POWs in the Pacific Theater of War.[10]

Of primary importance to the Japanese was the idea of place. Japan was at the hierarchy of nations. The emperor sat atop the Japanese caste system. He was not a man but a god. Detached from his people and accessible only to those privileged echelons of a stratified society. It was up to the military, the Japanese High Command, to run the Empire. And their doctrine was Hokku Ichiu, the Japanese equivalent of the German Lebensraum or Living Space. Indeed the militarists’ agenda was to rid Asia of the White Christian colonial powers of Europe. Asia for Asians!Of course, the intent was to establish Japanese mastery over their neighbors, to which Asians would be trading one overseer for another. Resulting, of course, in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere or the Japanese Empire.[11]And the militarists accomplished same by issuing directives in the emperor’s name whether he was aware of them or not. And what was more, dutiful Japanese believed and did what they were told.

Later in the war, when Radio Tokyo began to announce defeats, the Japanese were told that the High Command had expected such reversals, but that ultimate victory was assured. And the people believed it.

When the B-29s began to lay waste of Japanese cities with impunity, the Japanese people were told that the High Command had expected such attacks and were prepared to deal with the situation. And the people believed it.

Such was the grip that the militarists had on the Japanese people. A hold the High Command had no intention of relinquishing. Even if it meant wholesale destruction of Japan.

* * * * *

Much of the terrain in Japan is mountainous, with ridges and forests, from which a determined defender can exact a hefty price from an attacker.

White House Chief of Staff, Admiral William Leahy pointed out to President Truman, “. . . that the troops on Okinawa had lost 35 percent in casualties. If this percentage were applied to the number of troops to be employed in Kyushu, [for Operation:OLYMPIC, November 1, 1945], he thought the similarity of fighting to be expected would give a good estimate of the casualties to be expected. He was interested therefore in finding out how many troops are to be used in Kyushu.”[12]To which General George Marshal pointed out:

“. . . that the total assault troops for the Kyushu campaign were shown in the memorandum prepared for the President as 767,700. He said, in answer to the President’s question as to what opposition could be expected on Kyushu, that it was estimated at eight Japanese divisions or about 350,000 troops. He said that divisions were still being raised in Japan and that reinforcement from other areas was possible but it was becoming increasingly difficult and painful.”[13]

Indeed, the Japanese were preparing for an invasion of their home islands by those White Christian powers they had sought to remove from Asia. Operation:KETSU-GO or Operation:DECISION.

Phase One was to feature submarine attacks.“Of the 45 remaining submarines, about 38 were operational in Japanese waters and would be the first thing U.S. forces would encounter. Although an opportunity to sink a carrier would not be passed up, the troop transports were top priority. A few of the Japanese submarines were equipped to carry “Kaiten” manned-suicide torpedoes and about 120 Kaitens would be immediately available for use, although some estimates for the number of Kaitens that would have been available by November range as high as 1,000. Although the Kaitens had proved largely ineffective in open-ocean use, the Japanese anticipated much better success in the confined and crowded waters of an amphibious beachhead, which probably would have been the case.”[14]

Expected, too, were the “Koryu” midget submarines. Some 540 of the five-man subs, each capable of two torpedoes or explosive charges, were augmented by about another 740 more advanced midget submarines known as the “Kairyu.”Each of these carried two torpedoes or an explosive charge. However, Koryu production was severely impacted by bombing and only 110 were complete when the war ended, and only 250 of the kairyu had been completed.”[15]

The Imperial Japanese Navy was to unleash some 3,300 “Shinyo” motor boats mounting a 550 pound explosive charge with the express purpose of ramming American ships and landing craft. Some of these were manned by Army personnel and even featured depth charges. Actual number available was about 800. In addition, the I.J.N. was going to commit its remaining destroyers, perhaps 19 vessels, in suicide runs against the invasion fleet.

The “Forkuryu” or suicide frogmen were slated to swim out among the landing craft and attack them with explosive charges. Some 4,000 were expected to be ready by November 1945.

Kamikaze planes were not committed for the first attacks. At places such as the Philippines and Okinawa, despite incurring much damage to the U.S. fleet, many were still shot down on the way to making their attacks. Here they were to be unleashed when the invasion fleet was right off the beaches. This allowed for the minimum of flight time when compared to the attacks at Okinawa.

Due to the proximity of the battle front, Kamikaze aircraft were dispersed among dozens of airfields, and then were concealed and camouflaged. With their preparations, upwards 12,700 aircraft of all types had been accumulated. Not all were warplanes, with some even made of wood.“The Japanese Army air attack plan called for aircraft to attack in waves of 300-400 aircraft, at a rate of one wave per hour, day and night, until all aircraft and pilots were gone. The Navy preferred to conduct attacks at twilight, and that discussion was still inconclusive at the end of the war. Nevertheless, this level of effort would have resulted in more kamikazes attacks in three hours than in three months of the Okinawa campaign, and would have had a great prospect of saturating the defenses of the transports when they were most vulnerable.”[16]

Phase Two would have been the ground fighting. On June 18 1945, in a meeting in the Oval Office with President Truman, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, together with Admiral William Leahy, General George Marshall, Admiral Ernest King and Army Air Force commander, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, were being briefed by General Marshal on the Japanese ground forces capability to be faced with the November 1945 invasion of Kyushu. Estimates were some 350,000 Japanese troops. In addition, all Japanese civilian workers for the Army and Navy were to be armed, perhaps some 4,000,000. Added to which was the Japanese People’s Volunteer Corps. All women, ages 17-40 and men 15-60 were included, armed with bird guns, bows and arrows, swords, sharpened stakes, knives, . . . Population on Kyushu alone was 2,400,000.

Not counting Allied troops, it was estimated that Operation:DOWNFALL, overall program to which Operation:OLYMPIC, invasion of Kyushu and Operation:CORONET, invasion of Honshu, March 1946, would require 1,700,000 American soldiers and marines. Casualty expectations of the former were some “124,935 battle casualties, including 25,000 dead, plus 269,000 non-battle casualties (disease, accident, etc.) for Kyushu alone. The J.C.S. came up with an estimate that a 90-day campaign on Kyushu would cost 156-175,000 battle casualties, with 38,000 killed in action. By late July, the J.C.S. was forecasting 500,000 casualties at the high end and 100,000 at the low end. In late July, the War Department provided an estimate that the entire DOWNFALL operations would cause between 1.7 to 4 million U.S. casualties, including 400-800,000 U.S. dead, and 5 to 10 million Japanese dead.[17]

* * * * *

November 26, 1943, President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek concluded their conference in Cairo.“The several military missions agreed upon future military operations against Japan . . . The three great Allies are fighting this war to restrain and punish the aggression of Japan . . . With these objects in view the three Allies, in harmony with those of the United Nations at war with Japan, will continue to persevere in the serious and prolonged operations necessary to procure the unconditional surrender of Japan.”[18]

Unconditional surrender will prove to be a sticking point. Let us start with the Emperor, what is he to think?Do the Allies plan to try him for war crimes?Perhaps extinguish the royal institution and the notion of his majesty as a living, breathing god on earth?The militarists, though are committed to a foregone conclusion:Fight to the last to protect the sacred homeland of Japan from these infidels.

Middle of 1944, the war had been taking a decided turn for worse for Japan, to which a council will be formed:The Supreme Council for the Direction of the War. Included were “the Premier, Foreign Minister, Ministers of War and Navy, and Chiefs of the General Staffs of the Army and Navy.”But as Japan’s situation became increasingly dire, changes to the personnel were made. Hence the rise of the Big Six.

“These six men were important; for they formed the ‘inner cabinet’ which made decisions at the highest level for the cabinet, and then for the Emperor, to approve. They were Premier Admiral Baron Kentaro Suzuki, Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo, War Minister General Korechika Anami, who was the most powerful man in Japan at the time; Navy Minister Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai; Army Chief of Staff Yoshijiro Umezu, who looked like an Oriental Mussolini and was even more dictatorial; and, Navy Chief of Staff Soemu Toyoda, an eloquent, sixty-year old xenophobe. He was put in by Suzuki to replace Oikawa, the earlier member, because Toyoda belonged to the same general clan as Anami and Umezu, and the Premier thought he would be able to help turn the two Army men from their hardline attitude.”[19]

On the diplomatic front, negotiations with the western powers were viewed as unproductive in Tokyo. But what about the Russians?Perhaps through Moscow, the Japanese could arrange a “conditional peace,” in lieu of unconditional surrender.

On the heels of the disastrous defeat at Okinawa, Emperor Hirohito and Marquis Koichi Kido, favored bringing the conflict to a conclusion. They felt buoyed since Admiral Suzuki and Shigenori Togo had joined the “inner cabinet.”Contact was made with the kremlin.

“July 21, the Japanese government instructed its representative in Moscow, ‘We cannot consent to unconditional surrender under any circumstances. Even if the war drags on and more blood must be shed. So long as the enemy demands unconditional surrender, we will fight as one man against the enemy in accordance with the Emperor’s command.’”[20]

Yalta Conference, early February 1945, where Stalin ‘promised’ to enter Pacific War three months after the capitulation of Nazi Germany. This will be the final Big Three conference of Churchill, FDR and Stalin. For President Roosevelt will die, April 12, 1945.

American codebreakers were reading Japanese diplomatic traffic and knew of the Kremlin contact. Stalin, in the end, had no intention of assisting the Japanese. He had made a “promise” at Yalta to come in to the Pacific War three months after the Germans had surrendered. And that was exactly what he going to do. However, on the American side, another multi-power occupation of Japan as with Germany was unacceptable. Japan was going to be occupied by the United States alone. For depending how long the Japanese held out against an Allied invasion of the Home Islands, just how much of Manchuria and Korea were the Soviets going to gobble up?So despite naysayers such as Admiral Leahy, General Eisenhower and others, Truman will play it close to the vest until he decides on dropping the Bombs.

The Big Three at the Potsdam Conference, July 1945. Left-to-Right, Clement Atlee, U.K., President Harry Truman, U.S. and Generalissimo Joseph Stalin, U.S.S.R.

On July 26, 1945, from the Potsdam Conference was released, The Potsdam Proclamation; and as noted by:“Proclamation by the heads of Governments, United States, China and the United Kingdom.”Among the points urging the Japanese to come to terms with the realities of the war at this juncture were:

(8)The terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out and Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine.

(9)The Japanese military forces, after being completely disarmed, shall be permitted toreturn to their homes with the opportunity to lead peaceful and productive lives.

(10)We do not intend that the Japanese shall be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation, but stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals, including those who visited cruelties upon our prisoners. The Japanese government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people. Freedoms of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental human rights shall be established.[21]

Reference to the Cairo Declaration in point 8 meant unconditional surrender. In addition to the fact no reference to the Emperor could be found. This will not be acceptable to the Japanese.

Fall, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito. Hirohito’s role in Japan during the war is still very much open to debate, even today.

Yet by the day prior to the release of The Potsdam Proclamation, July 25, “the bomb-as-a-weapon was generally believed to be unnecessary—as Truman had by then been told by Leahy, Eisenhower, King, Arnold and Le May and others. General Douglas MacArthur, then Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Pacific, was not asked for his opinion whether the bomb was of any military use against Japan. Only General Marshall continued to hedge on his opinion, and he was profoundly disturbed at the thought that the attack was to be a surprise. He would later say the bomb shortened the war by months; Le may said it shortened the war by two weeks. Churchill was to say, ‘It would be a mistake to suppose that the fate of Japan was settled by the atomic bomb, her defeat was certain before the first bomb fell.’”[22]

As to the Japanese, whether militarists or no, The Potsdam Proclamation was a regurgitation of the Cairo Declaration. So their response was “Mokusatsu.”“Literally the word means ‘kill with silence.’”[23] In American parlance, perhaps, “No Comment.”

At this stage of the saga, Stalin was moving troops, tanks, guns and planes to the Manchurian border. Truman was under no illusions that Stalin was committed to entering the Pacific War, as prescribed at Yalta. This led to the model issue of concern, that Germany was to be divided into four parts. This was not what the United States was going to allow in Japan. Washington was not going to allow any kibitzers here, even if they were allies; an early indication of America employing its new-found power. So Truman, then, will give the order and Hiroshima will be vaporized, August 6, 1945.[24]

The Emperor, upon being informed about the tragedy at Hiroshima, realized that Japan must accept the inevitable. He ordered the War Council to meet to formalize some sort of surrender offer. The meeting was scheduled for August 9, the same day Nagasaki was vaporized and Stalin unleashed his Far Eastern Army against the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria.

Japan’s position was untenable. In a meeting called for in the Imperial Palace for August 10, the Supreme War Council, including the Big Six was convened. Among them were those who would prefer to come to terms versus those who wanted to fight to the bitter end, no matter the cost. It was then Hirohito who decided the issue, surrender.

A note was forwarded to Secretary of State, Jimmy Byrnes, via Swiss intermediaries, which included, “The Japanese Government are ready to accept the terms enumerated in the joint declaration which was issued at Potsdam on July 26, 1945 . . . with the understanding that the said declaration does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign Ruler.”[24]

The Emperor recorded two transcripts to be read over the air waves to the Japanese nation on August 15. Army militants broke into the Imperial Palace the evening prior to destroy the transcripts. They failed. The message of surrender was beamed to the nation and the war was over.[25]

* * * * *

Postscript

The bombs capped the destruction of Dai Nippon Teikoku or The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, AKA the Japanese Empire. In addition, Hiroshima and Nagasaki destroyed an Oriental version, perhaps, of the Devine Right of Kings, the belief that the Emperor was a god on earth. The obvious emptiness of this belief was that this earth-bound divinity failed and failed miserably to prevent the wholesale destruction of much of Japan. Recall, too, what the irate French masses did to Louis XVI in January 1793.

Stalin understood what the atomic bombs meant. A shortening of the war and a warning to the Soviet Union that America had the “doomsday” weapon as some were already calling it and would employ same if the situation required. Of course, America’s monopoly would end in only four years when the Soviets would successfully test their own version of the atomic bomb.

It has been offered from many quarters over the years that with Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United States began the nuclear arms race. A falsity easily refuted when one understands that Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman of Germany first split the atom in 1938. Nazi Germany, then, was the first out of the starting gate on the road to a nuclear weapon. Germany, though, will eventually lose its lead with its attempt to racially profile the science as “Jewish Physics.”In the end not a surprise here since Fascists many times seem regard the most outlandish of stupidities over accomplished facts such as those found in science. Britain will throw its lot with the United States. For the Manhattan Project will be seen by many of its participants as a race to achieve the bomb before the Germans. The idea of Hitler in possession of such a weapon was an anathema.

Another combatant was working on the bomb as well, . . . Japan. There were two programs, the Army’s and the Navy’s. Much of the research was carried out in North Korea, at Konan or what is more popularly known as Hungnam. One of the scientists involved was Yoshio Nishina, a colleague of Niels Bohr. On page 16, of the Introduction of Robert K. Wilcox’s, Japan’s Secret War, there is reference to a 1946 account, made public by David Snell, who had been an agent with the Twenty-Fourth Criminal Investigation Detachment in Korea, who had had a conversation with a Japanese officer in charge of the security for the Japanese project. He related a bomb test off the Korean coast on August 10, 1945. The objective was to employ atomic bombs on Kamikaze planes for use against American troops on landing beaches.[26]

Regardless, many chemists and physicists knew the use of atomic energy for war or peace was possible and for quite a long time prior to 1945. But in the end, atomic energy’s use as a weapon was entirely compatible with Levee en Masse, the conscription of entire populations and economies for war. From 1793 to 1945, this notion of Total War had evolved. The need to expand manpower pools beyond that of professional soldiers and volunteers had arrived. For with more factories more weapons could be produced. And with the evolution of technology funded by capitalism, each new mark of weaponry was reaping an ever greater harvest of humanity. And as men filled out uniforms, women were needed in the factories to produce the implements of war. Societies, economies and war itself will be irrevocably altered by Levee en Masse.Organizing nations for just one thing, win the war. And this necessitated Central Control; in other words, the era of Big Government had arrived.

I have always assumed that the Japanese would have done whatever they could todevelop the atomic bomb during the war, and if they had it, would have used it. I have always assumed that any country that could have had the bomb during the war would have used it, the Nazis, the Soviets, and the Japanese. So we are not unique.Edwin O. Reischer, Harvard professor and former U.S. ambassador to Japan.[27]

Endnotes

[1]Genzai Bakudan (Greatest Fighter) was the codename for the Japanese atomic bomb program in World War II. It is also the title name for Chapter 4 in On History:A Treatise, by Mark Albertson.

[2]See page 55, Chapter 4, “Genzai Bakudan,” On History:A Treatise, by Mark Albertson.

[3]See pages 205 and 206, “Acceleration,” Ruin From the Air, by Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan Witts.

[4]See page 5, “U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey:The Effect of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 1946,” Department of Defense, Japan, publicintelligence.net/ussbs-hiroshima-nagasaki

[5]See pages 373 and 374, “The Great White Light,” by Major Gene Gurney, Combat:The War With Japan, edited by Don Congdon. See also page 56, Mark Albertson.

[6]Major Sweeney would later fly the bomb plane to Nagasaki, Bock’s Car, and become the only pilot to fly both atomic bomb missions.

[7]Per the Strike Order for Hiroshima, posted 5 August 1945, a total of six B-29s took part in the mission. Tibbets’ bomb plane. The instruments and camera planes and the three weather planes which took off first.

[8] Per the Authorization of the Dropping of the First Atomic Bomb, from Acting Chief of Staff, United States Army Air Forces, General Thomas Handy to General Carl Spaatz, Commanding General, United States Army Strategic Air Forces, posted July 25, 1945, there were listed four targets:Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata and Nagasaki.

[9]It is indeed unfortunate that Japanese military personnel, officers as well as rank and file, not only shot out of hand Allied prisoners of war, but on occasion, feasted on the dead. Note, please, “the text of a captured Japanese order on the subject of cannibalism and some extracts from the interrogation of a Japanese officer, Major Matoba, who was questioned about the practice of cannibalism by a military commission in August 1946 by the United States Navy commander of Guam and the Marianna Islands:

ORDER REGARDING EATING FLESH OF AMERICAN FLYERS

I. The battalion wants to eat the flesh of the American aviator, Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Hall.

II. First Lieutenant Kanamuri will see to the rationing of this flesh.

III. Cadet Sakabe (Medical Corps) will attend the execution and have the liver and gall bladder removed.

Battalion Commander:Major Matoba.

Date: 9th March 1945.

Time: 9 A.M.

Place: Mikazuki Hill Headquarters.

Method of issuing orders: Called to my presence First Lieutenant Kanamuri and Cadet Sakabe and gave verbal order.

Place to report after completion of order:Brigade Commander:Major General Tachabana.

Also informed:Divisional HQ Detachment, Major Horie, 308th Independent Infantry Battalion.” See page 236, Chapter XII, “Cannibalism, Vivisection and Mutilation,” The Knights of Bushido, by Lord Russell of Liverpool.

[10]“The extent of the ill-treatment, however, can be appreciated from this significant comparison. In the European theaters of war, 235,473 British and American prisoners of war were captured by the Germans and Italians. Of this number, 9,348, or 4 percent of the total, died in captivity. In the Pacific theaters of war the percentage was 27.”See page 57, Lord Russell of Liverpool.

Lord Russell of Liverpool is bolstered here by Yuki Tanaka, a one-time visiting Research Fellow at the Australia National University. To which the following:

Number of Allied POWs and Death Rate Under the Japanese:

Country Number of POWs Number of Deaths Death Rate (Percent)

Australia 21,726 7,412 34.1

Britain 50,016 12,433 24.8

Canada 1,691 273 16.1

New Zealand 121 31 25.6

United States 21,580 7,107 32.9

Holland 37,000 8,500 22.9

Total: 132,134 35,756

Average Death Rate: 27.1

See page 3, “Introduction,” Hidden Horrors, By Yuki Tanaka.

[11]Stalin had something to say along the lines of Japan’s effort towards empire.“. . . whoever occupies a territory also imposes on it his own social system. Everyone imposes his own system as far as his army can reach. It cannot be otherwise.”See page 114, II, “Doubts,” Conversations With Stalin, by Milovan Djilas.

[12] See page 907, Foreign Relations of the United States:Diplomatic Papers, The Conference of Berlin (The Potsdam Conference), 1945, Volume I, J.C.S. Files, No. 598, Memorandum by the Secretary of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (McFarland), Washington, June 18, 1945 at 1530.

[13]See page 908, Foreign Relations of the United States:Diplomatic Papers, The Conference of Berlin, (The Potsdam Conference), 1945, Volume I . . .

[14]See page 5, “H-057-1:Operations Downfall and Ketsugo-November 1945,” by Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command, January 2021.www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/…

[15]See pages 5 and 6, Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command.

[16]See page 8, Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command.

[17]See page 10, Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command.

[18]See page 1, Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States:Diplomatic Papers, The Conferences at Cairo and Tehran, 1943, Final Text of the Communique, Press Conference, November 26, 1943.

[19]See pages 39 and 40, Chapter II, “The Long Bumpy Road to War and Peace,” Nagasaki:The Necessary Bomb? By Joseph Laurence Marx.

[20]See page 33, Chapter 3, “To Save ‘Half Million’ American Lives,” Hiroshima, by Ronald Takaki.

[21]See pages 1 and 2, Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States:Diplomatic Papers, The Conference of Berlin (The Potsdam Conference), 1945, Volume II, No. 182, Proclamation.

[22]See pages 238 and 239, Chapter 17, “Mokusatsu,” Meeting at Potsdam, by Charles L. Mee, Jr.

[23]See page 248, Charles L. Mee, Jr.

[24]Consult Appendix D, page 167, “Agreement Regarding Entry of the Soviet Union into the War Against Japan,” Such a Peace, by C.L. Sulzberger. To which can be added, here, that by well into July 1945, Washington saw no need for the Soviets being involved in the war in the Pacific. Indeed, Winston Churchill testified to this fact to Anthony Eden, July 1945. See page 639, Chapter 19, “Potsdam:The Atomic Bomb,” Triumph and Tragedy, by Winston Churchill.

[25]See page 102, Chapter V, “In the Palace Air-Raid Shelter,” Nagasaki:The Necessary Bomb? By Joseph Laurence Marx.

[26]“One group of Army officers rejected the imperial will. They planned a coup d’etat to seize power. Establish a military government, and continue the war. After a few days of plotting, they broke into the Imperial palace on the evening of August 14 in search of the emperor’s recording. They also intended to kill Premier Suzuki. The fanatics failed to stop the imperial broadcast. Most of the military knew that further resistance was impossible and quietly complied. The wretched fifteen-year war came to an end with a whimper instead of a gory bang.”See pages 231-232, Chapter 11, “Defeat,” The Pacific War, by Saburo Ienaga.

[27]See pages 15 and 16, “Introduction,” Japan’s Secret War, by Robert K. Wilcox.

[28]See page 13, Robert K. Wilcox.

Bibliography

Albertson, Mark, On History:Treatise, Tate Publishing & Enterprises, LLC, Mustang, Oklahoma, 2009.

Churchill, Winston S., Volume 6, The Second World War:Triumph and Tragedy, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts, 1953.

Congdon, Don, editor, Combat:The War With Japan, Dell Publishing Company, Inc., New York, NY., 1962.

Cox, Samuel J., Director, Naval History and Heritage Command, “H-057-1:Operations Downfall and Ketsugo-November 1945,” www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/…

Craig, William, The Fall of Japan:A Chronicle of the End of the Japanese Empire, Galahad Books, Edison, New Jersey, 1967.

Djilas, Milovan, Conversations With Stalin, Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc., New York 1962.

Dower, John W., Embracing Defeat:Japan in the Wake of World War II, W.W.Norton & Company, New York, NY., 1999.

Ienaga, Saburo, The Pacific War, Pantheon Books, Division of Random House, Inc., New York, 1978. Originally published by Iwanami Shoten Publishers, Tokyo, 1968.

Liverpool, Lord Russell of, The Knights of Bushido:A Short History of Japanese War Crimes, Cassell & Company Ltd., London, 1958.

Marx, Joseph Laurence, Nagasaki:The Necessary Bomb? The Macmillan Company, New York, NY., 1971.

Mee, Charles L., Jr., Meeting at Potsdam, M. Evans and Company, Inc., New York, NY., 1975.

Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States:Diplomatic Papers, The Conference In Berlin, (The Potsdam Conference), 1945, Volume I, J.C.S. Files, No. 598, Memorandum by the Secretary of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (McFarland). Historical Documents, Office of the Historian, history.state.gov/historical documents/frus1945…

Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States:Diplomatic Papers, The Conferences at Cairo and Tehran, 1943, Final Text of the Communique, Press Conference, November 26, 1943.History.state.gov/…/frus1943CairoTehran.d343

Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States:Diplomatic Papers, The Conference in Berlin (The Potsdam Conference), 1945, Volume II, No. 1382, Proclamation.History.state.gov/historical documents/frus1945…

Strike Order for Hiroshima, 5 August 1945, 509th Composite Group, Office of the Operations Officer, James I Hopkins, Jr., Major, Operations Officer.

Sulzberger, C.L., Such a Peace:The Roots and Ashes of Yalta, The Continuum Publishing Company, New York, NY., 1982.

Takai, Ronald, Hiroshima:Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb, Little, Brown and Company, Toronto, Canada, 1995.

Tanaka, Yuki, Hidden Horrors:Japanese War Crimes in World War II, Westview Press, Division of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., Boulder, Colorado, 1996.

Thomas, Gordon and Witts, Max Morgan, Ruin from the Air:The Enola Gay’s Atomic Mission to Hiroshima, Scarborough House/Publishers, Chelsea, Michigan, 1977.

Wilcox, Robert K., Japan’s Secret War:Japan’s Race Against Time to Build its Own Atomic, Bomb, William Morrow Company, Inc., New York. NY., 1985.