Looking Back, June 2025

By Mark Albertson

Rover Joe, Horsefly, Timothy and Pineapple

As with any other endeavor that is from the mind of man, there is that period of trial and error until that level of efficiency is hopefully attained. This was certainly the case with trying to reach a functioning system of joint forward air controllers so as to provide the ground forces with effective close air support. Following the campaign in North Africa and the 35-day Sicilian operation that resulted in the removal of Axis forces, it was not until the Italian campaign that greater efforts were made to improve the functionality and coordination between ground and air for CAS.

An issue for improving close air support was motivating the Army Air Forces towards a more avid interest in same. For after the war, as pointed out by historian Harry Cole, “’it is obvious that at the time of the Sicilian campaign much remained to be done in the improvement and coordination of techniques of air operations in close support of ground forces.’ Tactical air control inefficiencies largely stemmed from American air commanders’ reluctance to become involved in the joint planning effort, which was an apparent result of the Mediterranean Air Command’s intent to assert its recently acquired autonomy. The situation only began to improve after U.S. Fifth Army Commander General Mark W. Clark made an emphatic request for better air integration, and Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower issued a virtual directive for a more active tactical air support role from the ‘so-called Strategic Air Force.’”[1]

Cooperation between air and ground forces improved. This despite the fact that German resistance caused the Allied advance up the Boot to slow and even grind to a halt, going into the spring 1944.[2]

Improved cooperation between ground forces and air staffs resulted in a command and control procedure that was sophisticated enough to accommodate the lowliest of requirements. Missions to be requested for action the following day would be sent up the food-chain of command until it reached the Corps level. Here staff would coordinate CAS requests with Army level. Army and air staffs huddled for evening meetings. Missions would be scheduled, depending, of course, on the availability of aerial assets.

But then there was the fluid situation, an urgent request for support from the front that required immediate attention. This was the “call request.”

“Call requests for air support against rapidly developing targets originated with a radio call from the front-line requesting agency to the division. The division immediately passed the request up to the joint air-army control center at the army headquarters, while the corps and army commands monitored the net, offering tacit approval for the request with their silence. Final approval for the request came from the army and air force operations officers at the control center. ‘Approved’ missions were tasked to air units operating on alert status in the air operations directive. Call missions frequently achieved their goal of having aircraft on-station within ninety minutes of the initial request. While formalizing the air tasking process greatly contributed to the operational availability of CAS aircraft, the introduction of forward air controllers enabled tactical air ground integration.”[3]

The forward air controllers were a tactical improvement for the integration of air-ground cooperation. AKA “Rover Joes,” their function was to insure the success of pilots answering the call-request owing to the lack briefing prior to the mission. Yet Rover Joes proved useful for scheduled missions or call-requests.

The Rover Joes were devised by the XII Air Support Command. These were generally made up of an Army Air Forces officer (pilot) and a ground forces officer working from a concealed position at the front. Hill tops were sought because of the advantage offered for a more commanding view of the battle area. “Their radio equipment, behind the hill out of sight of enemy observers and protected from enemy fire, was operated by enlisted personnel who communicated by telephone to the observation post.[4] Ground units seeking the elimination of attacking enemy forces or those enemy strongpoints offering resistance to an offensive were primary targets of opportunity.

The process entailed the ground forces, when seeking air support for the elimination of an enemy target, radioed the Rover Joe unit. Clearance was required by air and ground officers at the ground-air control center. Once this was done, the Rover Joe radioed the fighter-bombers which were nearby so as to conduct their attack.

The Rover Joe controller, using maps and aerial photographs, briefed the flight leader as to the features of the terrain as well as having the artillery mark the target area with colored smoke. The fighter-bombers would then give the target a going over with strafing runs and or bombing. The Rover Joe unit would then record the results of the attack. Indeed, the whole process could take less than 15 minutes.[5]

Direct radio contact between Rover Joe units and supporting fighter-bombers improved close air support efforts for the ground forces. Regardless, though, it was still not the adequate solution that was needed. Being on the ground, many times Rover Joe controllers and observers could not find suitable positions for observation. Many times the view was restricted to only several hundred yards of front. Hardly a panoramic view. British criticism included that the Rover Joe system worked better within static situations as opposed to actions of a more fluid nature, which could result in the bombing or strafing of friendly troops. What was required, then, was an unrestricted view, one that offered a constant visual contact of enemy positions. This could only be done from the air. This led to the introduction of the “horsefly.”[6]

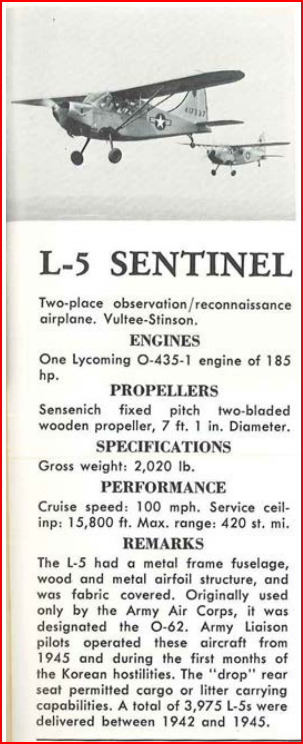

L-5 Sentinel Specifications

Horsefly planes were referred to as such in Army Air Force transmissions. Since they were needed close to the front, the horsefly operated off ground forces airstrips near the front lines. The Stinson L-5 was the plane and was usually flown by an AAF fighter-bomber pilot assigned on temporary duty and, was generally from the fighter-bomber squadron assigned for ground support operations. The observer was from the ground forces and from the unit to which the horsefly had been attached.

Horsefly aircraft were distinguished by stripes painted atop the wings, perhaps red or orange. Such would identify this particular liaison plane from any other along the same front.

Preparatory to each mission, horsefly crews were briefed. Maps and aerial photographs of the target in question were employed to ready the pilot and observer. Indeed, such briefings were the result of an aerial reconnaissance of the front conducted by the horsefly.

Once taking off, the horsefly rendezvoused with the fighter-bombers it was to direct behind friendly lines. Then it was on to the target.

Once at the target, the horsefly would direct the fighter-bombers by radio; and, if need be, mark the target with smoke grenades. At times, horsefly crews were only thirty feet from the ground when dropping smoke grenades so as to assure the destruction of the target.

“On 29 June [1944] an experiment was made using 1st Armored Division L-5s to direct fighter plane attacks. The controllers were air officers who flew in four L-5s, each painted a different color for identification (Horsefly Yellow, Horsefly Blue, etc.). The experiment was not considered a complete success, but it did prove the idea was practical.”[7]

The British were hardly keen on the horsefly principle, considering the ground observation principle more efficient despite its limitations. The Americans differed here as to the aircraft’s ability to offer a wider view of the battlefield. Americans thought, too, that the horsefly principle would prove more successful on a fluid battlefield. As to the vulnerability of the flivver plane, it was believed by Americans that the L-5 could operate at an altitude of 6,000 feet and five miles behind enemy lines. That is, of course, that air superiority had been established. And once into 1944, this was becoming and ever present reality.

Another attempt at establishing a functioning close air support technique was that of “Timothy.” This was first used in the Italian campaign on November 12, 1944, “when Desert Air Force Pilots provided close support for a British brigade offensive. An Eighth Army history states: ‘[It] took the form of a ‘Blitz’ in a limited area on either side of the brigade’s axis of advance, to a depth of about 1,000 yards, in front of a smoke bomb line. Three attacks had been prearranged (at 0730, 0830 and 0930) each consisting of 24 aircraft. Results were so good that the attacks were repeated. . . .’

“By the end of the day, the brigade had advanced 2,000 yards and taken 106 prisoners at a cost of 13 casualties. Timothy was undertaken again the next day with both British Spitfires and American P-47 Thunderbolts participating, and it continued to be used for the remainder of the campaign.

“Timothy’s essential prerequisite was that it had to be tied in with a ground offensive whose forces had to take immediate advantage of the air attack. The land formations had to furnish precise information on positions, targets and timing. It was also imperative that two safety factors be observed: (1) the local Rover must control the operation, ordering the smoke bomb line only after pilots had announced they were in the area, and then giving orders to attack and to cease; and, (2) pilots must be briefed not to attack unless both the smoke bomb line had been laid according to plan and Rover had expressly given his permission. This type of operation could degenerate into ‘area bombing’ rather than for an advance in a specific, heavily defended sector, but it did prove effective on a number of occasions.

“Another widely used technique, called ‘Pineapple,’ was designed to strike lucrative moving targets discovered by tactical aircraft on reconnaissance missions. Most often, the reconnaissance pilot radioed the army-air control center in the clear, indicating the target location, direction of movement, and composition. If the air force representative could accept the request for attack, the control center immediately passed it on to Pineapple-designated aircraft on alert, which at times were able to reach the target area within 15 minutes of receiving the order. The reconnaissance pilot would assist fighter-pilot pilots in locating the target. If the target was not clearly visible, the reconnaissance pilot might even lead the attacking flight to it. Occasionally, in addition to the control center, the reconnaissance pilot might contact a Rover for support. If the control center gave permission, Rover selected a rendezvous point from which the reconnaissance pilot picked up the fighter-bombers to lead them to the target. Since enemy ground or anti-aircraft fire could make an attack on the target too dangerous, the leader of the Pineapple flight could still the situation by using the code-word Nuts.[8]

Following the Allied success at Normandy, the horsefly continued to be used in France. This was particularly true with First and Third Armies. According to Ken Wakefield, “The Third Army employed Horsefly operations for the first time during its offensive in the Saar, two L-5s giving coverage from dusk to down. The technique was used with great success, the airborne controllers directing numerous fighter-bomber strikes against both pre-arranged and opportunity targets during the drive to the Rhine and beyond. The 9th Infantry Division also used its liaison aircraft to direct fighter-bomber attacks and found those against targets of opportunity, where there was no time to brief pilots, particularly rewarding. Approval of the method was also to be found in a report by VI Corps which stated that Horsefly was responsible for much effective bombing of Siegfried Line fortifications. In addition, vast amounts of enemy material was destroyed by air-directed close support in its drive to the Rhine and on into Bavaria and Austria. Nevertheless, Horsefly was not without its critics and there were those who favored control of fighter-bombers by similar high-performance aircraft; certainly, as the critics argued, Horsefly operations were feasible only where air superiority enabled slow, unarmed and unarmored aircraft to operate with relative immunity.”[9] Such criticism had dogged horsefly ever since it was introduced in Italy.

Of course, as with any other aspect found in war, horsefly was not without its human cost. Again, Wakefield: “On Christmas Eve (1944), Technical Sergeant Charles W. Leipersock, flying L-5 42-99605 on a Horsefly mission, with Major Randolph M. Jordan of the 10th Armored Division, failed to return to the squadron’s strip in Luxembourg. Sometime later it was learned that the L-5 had crashed near Ettelbruck, shot down in flames by flak. Sergeant Leipersock managed to bale out and was taken prisoner by a German tank crew, but nothing further is known of Major Jordan. Later at the end of April 1945, Charles Leipersock was released from captivity by the Third Army and was flown back in an L-5 from Landshut, Germany, for a memorable reunion with his squadron colleagues.”[10]

Data: Republic P-47 Thunderbolt

The razor-back P-47D, with its eight .50 caliber machine guns. At 17,500 full-load tons, the Thunderbolt was the heaviest single-engine fighter in World War II. Indeed, the P-47 was only 4,000 pounds less than the twin-engine Bristol Beaufighter.

The P-47 Thunderbolt was a fighter plane, bomber escort and utilized as a fighter-bomber for the interdiction role and close air support. The “Jug” was rugged yet speedy and with its eight .50 caliber machine guns packed a lethal punch. At seven and one-half tons, it was the heaviest single-engine fighter of World War II. And in its ground-support role, P-47s could take a punch. This writer knew a P-47 pilot who flew 85 missions in ground-support. His plane was replaced five times; but, all of his rides, shot up as they were, got him home.

| Power plant | One 2,535 hp Pratt & Whitney R-2800-59 Double Wasp Radial. |

|---|---|

| Wing span: | 40 feet, 9 inches. |

| Length: | 36 feet, 1 inch. |

| Height: | 14 feet, 2 inches. |

| Weight empty: | 10,700 pounds. |

| Weight loaded: | 17,500 pounds. |

| Crew: | 1 pilot. |

| Max speed: | 433 mph at 30,000 feet. |

| Service ceiling: | 42,000 feet. |

| Normal range: | 590 miles. |

| Armament: | Eight .50 caliber machine guns; up to 2,500 pounds of bombs or ten Rockets.[11] |

A diving P-47 Thunderbolt loosing missiles at a ground target.

According to data supplied by Republic Aviation Corporation, the P-47 during “World War II dropped 132,482 tons of bombs, expended over 135 million rounds of ammunition and some 59,567 rockets and several thousand gallons of napalm. 3,752 enemy aircraft were claimed to be destroyed in the air, and a further 3,752 on the ground. This effort required 1,934,000 flying hours and 204,504,000 gallons of fuel.

“Two-thirds of all P-47s produced eventually found their way to USAAF units in combat theaters, and losses of aircraft on operational missions were only 0.7 percent of those dispatched. From D-Day to V-E Day in Europe, the P-47 low level strikes accounted for 86,000 railway wagons, 9,000 locomotives, 6,000 armored vehicles and tanks, and 68,000 motor trucks. The total P-47 production consisted of 15,683 aircraft, some 31 Thunderbolt groups being in action in 1944.”[12]

Endnotes

[1] See page 28, Chapter 2, Literature Review, World War II, “Rebuilding the Joint Airborne Forward Air Controller Analyzing Joint Air Tasking Doctrine’s Ability to Facilitate Effective Air-Ground Integration,” by Major David Scott Chadsey, USAF, 2013.

[2] Fifth Army’s way to Rome was blocked for weeks owing to the German control of the commanding heights of Monte Cassino. “Monte Cassino—Monastery Hill, as it became known to the men of many nations who fought under its shadow for so many weeks—completely controlled both the valley that lay before it and also the Liri River to the northwest. Route 6 runs up to, then around the foot of the southern flank of Monastery Hill, having passed through the little town of Cassino which itself snuggles under the haunches of the 1,600 foot hill. From the summit of Mount Cassino, an observer could watch any movement in both the valleys, and by artillery and mortar fire seal off the vital artery to Rome, Route 6.” See pages 18 and 19, Chapter 2, “The Germans Come to Cassino,” The Battles for Cassino, by Brigadier General E.D. Smith.

[3] See page 30, Major David Scott Chadsey.

[4] See page 209, Chapter 5, “Allied Cooperation in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1945,” Case Studies in the Development of Close Air Support, edited by Benjamin Franklin Cooling.

[5] The British employed a like system to Rover Joe. Though when dispatching support aircraft it was generally six fighter-bombers as opposed to the American four aircraft. See page 209, Benjamin Franklin Cooling.

[6] See page 93, IV, “Couriers and Angels,” Jeeps in the Sky, by Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Ten Eyck.

[7] See page 144, Chapter III, “The War Years, North Africa, Sicily and Italy,” The Army Aviation Story, by Richard Tierney with Fred Montgomery.

[8] See pages 218 and 219, Benjamin Franklin Cooling.

[9] See page 118, Chapter Eighteen, “16th December 1944-25th January 1945: The Battle of the Bulge and War in the Rhineland,” The Fighting Grasshoppers, by Ken Wakefield.

[10] See page 123, Ken Wakefield.

[11] See page 141, “Republic, P-47 Thunderbolt,” Aircraft of World War II, by Kenneth Munson.

[12] See pages 14 and 16, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, Described, Part I, by Geoff Duval.

Bibliography

Cannon, Hardy D., Box Seat Over Hell, San Antonio, Texas, June 1985.

Chadsey, Major David Scott, USAF, “Rebuilding the Joint Airborne Forward Air Controller Analyzing Joint Air Tasking Doctrine’s Ability to Facilitate Effective Air-Ground Integration,” U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, December 13, 2013.

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin, editor, Case Studies in the Development of Close Air Support, Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force, Washington, D.C., 1990.

Duval, Geoff, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, Described, Part I, Kookaburra Technical Publications, Dandenong, Victoria, Australia, 1969.

Eyck, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Ten, Jeeps in the Sky, Commonwealth Books, New York, 1946.

Greenfield, Kent Roberts, Colonel of the Infantry, Army Ground Forces and the Air-Ground Battle Team Including Organic Light Aviation, Study No. 35, AD-A954 913, Historical Section, Army Ground Forces, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1948.

Love, Terry M., L-Birds: American Combat Liaison Aircraft of World War II, Flying Books International, New Brighton, Minnesota, 2001.

Munson, Kenneth, Aircraft of World War II, Ian Allen, Great Britain, 1962.

Raines, Edgar F., Eyes of Artillery: The Origins of Modern U.S. Army Aviation in World War II, CMH Pub 70-31-1, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 2000.

Smith, Brigadier General E.D. Smith, The Battles for Cassino, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1975.

Tierney, Richard with Montgomery, Fred, The Army Aviation Story, Colonial Press, Northport, Alabama, 1963.

Wakefield, Ken, The Fighting Grasshoppers: U.S. Liaison Aircraft Operations in Europe, 1942-1945, Mid Counties Publications, Leicester, England, 1990.

Looking Back, May 2025

By Mark Albertson

80th Anniversary of World War II:

Army Aviation: The Pacific Theater

Combat conditions in the Pacific Theater of Operations differed from those in the European Theater. From the start, the war in the West was, for the most part, of a conventional type: Infantry, artillery, armor, used on a scale not seen in the Pacific. From the North African Desert, onto Sicily, up the Italian boot and across the French countryside into Germany, armies were employed on a level conducive to the precepts of maneuver and mobility, combining ground power with airpower as the Allied advance rolled up the outnumbered German armies.

In the Pacific it was a different story. The Allied strategy was based on naval power. As the United States Navy recovered and rebounded from the debacle at Pearl Harbor, Allied fortunes rose, spurring success after success. In other words, the Island-Hopping Campaign. Unlike the more conventional approach to war in the ETO, the Allied approach to war in the PTO amounted to a modern version of Siege Warfare. As the U.S. Pacific Fleet wrested control of the world’s largest ocean from the Imperial Japanese Navy, control of the seas reduced Japanese island bastions to hopeless positions of encirclement, condemning ill-fated garrisons to the dismal prospects of starvation when bypassed or certain destruction when Allied troops stormed ashore.

Early stages of the Island-Hopping Campaign did not see the mass employment of troops as compared to the ETO. For instance, the fall of 1944 there were forty U.S. Army divisions in the ETO as opposed to 21 in the Pacific, plus six Marine Corps divisions. Twenty-four divisions of the U.S. Army formed a strategic reserve.[1] It was really not until the latter stages of the campaign that an ETO equivalent of troops was committed in the Pacific, such as in the Philippines and Okinawa.[2]

In the PTO, many of the combat environments were jungle infested. This rendered difficult the employment of artillery. For instance, “In the initial island-to-island warfare, where difficult jungle terrain was often encountered, flash ranging was found impractical and was not attempted . . . On the other hand, sound ranging provided an excellent means of locating Japanese artillery and the adjusting of our artillery.”[3]

An example of operating in a dense jungle environment was New Guinea. So thick was the tangled jungle canopy, that it was not uncommon to find forward observers better able to direct artillery fire. Still intruding Cubs proved enough of a nuisance to garner the attention of prowling Zeros; for the Air OPs quickly became associated with the accuracy of the Field Artillery.

But uses for Cubs were found beyond that of their original intent. Being a rain forest, roads in New Guinea were rare and those that existed quickly became quagmires following heavy rains. Cubs were pressed into service as air taxis, hauling brass, delivering messages, moving supplies, transporting wounded in addition to reconnaissance and patrols.

Air OPs were employed to direct counterbattery fire onto Japanese gunners shelling American barges moving supplies along the coast; and, conversely directing American artillery onto Japanese barges.

Needless to say that in this jungle nightmare, there was always something for the Cub pilots to do. Captain Edwin Leer, a December 1942 graduate of Fort Sill, commanded a group of five L-4B Cubs, four sergeant pilots and himself. In the course of 2.5 months in the New Guinea jungle, Leer and his fliers logged 956 hours.[4]

A projected use of the Cub was flying “top cover” for an amphibious landing. “Just as the Lae show was getting under way it was found that the Jap might have evacuated Salamaua. No one was sure, however. (If you do not know Jap fire discipline and camouflage, such a situation may be hard to visualize.) Our forces slowly pushed in toward the town while 3 barges with assault troops were dispatched for a diversionary landing on the beach in front of the town itself. The barge-borne outfit would need plenty of help if the Jap was waiting, so it was decided to use a Cub for ‘top cover’—our artillery being registered on a base point near the beach, the Cub would fly in with the barges and direct fire in case of opposition. Undoubtedly the idea would have worked, but no opposition was encountered.”[5]

In the Philippines, spring 1945, from Loacan air strip, near Baguio, Air OPs of the 33rd Infantry Division, operated off an air strip some 4,000 feet up in the rugged mountains of Luzon. The aviators did more than fly artillery fire direction missions; they developed their own photographic section, scrounging equipment wherever possible. So successful was this effort in initiative that the Sixth Army artillery officer suggested that the practice be carried out in other divisions.

The forbidding terrain compromised close air support for the troops battling the stubborn Japanese. Cubs were thrown into action as pathfinders for bombing attack, dropping smoke grenades to mark targets for destruction. In 40 air strikes, this aerial combination resulted in no friendly fire incidents. Likewise Cubs were employed to lead C-47 pilots to their proper drop zones in the mountains so as to resupply troops on the advance. This enabled the supply planes to better navigate the mountainous terrain and deal with the hazardous air currents.[6]

But Leyte was more than just rugged mountains with hazardous air currents. Like New Guinea it was home to the ubiquitous jungle. And this is where the 11th Airborne Division found itself, slogging its way through the rainy, muddy, disease-ridden wallow to root out the entrenched Japanese. Liaison pilots found themselves supporting their comrades-in-arms in this fetid wasteland. As noted by Major Edward M. Flanagan, Jr., F.A., it “is the story of the overworked artillery air fleet doing a steam shovel’s job with a spoon.”[7]

To move supplies through the jungle, logs were used to cover the mud-caked roads. This did not always work, the logs sometimes sinking into the morass from the weight of the trucks. The Carabao, the indigenous pack animal used in the jungle, proved limited on the steep mountain tracks, which sometimes proved little better than inclined stream beds during torrential downpours. The troops themselves could not carry much in this unforgiving environment. Aircraft, though, proved invaluable.

The impenetrable Leyte jungle restricted drop zones or clearings for C-47s to adequately supply the troops. Not so the flivver planes. At Manarawat, a field dug out of the jungle was able to handle Cubs. Aviators flew in sections of a portable hospital which was then constructed. Doctors saved the lives of many wounded, sometimes operating under flashlights. Some of the wounded were delivered to doctor’s care by Cubs, thereby avoiding time-consuming treks through the jungle.

From the division artillery air fleet, some nine Cubs and 7 L-5s were put to work, delivering arms, ammunition and supplies to troops advancing in the Leyte jungles. At one point, the flivver planes delivered 21 tons a day, in a performance that would herald the work of rotary wing aircraft and crews in Korea and Vietnam.

Perhaps the last words are from a mortar platoon leader, when he wrote, “The liaison plane performed an outstanding job of resupplying the advance elements in the mountains. The difficulty of locating units in their small areas and the continuous bad weather made the liaison plane very effective. Their slow speed and maneuverability made them much more effective than higher performance aircraft.’[8]

China-Burma-India Theater

In the often referred to “Forgotten Theater” of war, the Army Air Forces was the primary employer of light aircraft. For instance L-4s and L-5s were used to fly engineers in an out of construction sites during the building of the Ledo Road—through northern Burma for the link up with the Burma Road from Lashio to Kunming—the epic supply route to the hard pressed Chinese Nationalist forces.[9]

Second most used Army cooperation aircraft of World War II and, will see duty in the Korean War. Used by the AAF, AGF and the Navy for aerial reconnaissance, medical evacuation, aerial taxi, . . . Appeared in almost every theater in World War II.

The L-1 or O-49 was found to be useful in the rugged Asian continent. While the C-47 proved invaluable for its trips over the Hump, delivering supplies and evacuating wounded, the L-1 proved invaluable in local evacuations, its power plant able to hoist it above much of the area’s mountainous terrain. Conversely, liaison pilots braved the hazards posed by the lower altitudes to airlift supplies, facing violent air currents which could send a flivver plane cascading out of control into a sheer mountain face or spiraling into the jungle floor below.

Seen as the plane that was America’s answer to the superlative Fiesler Storch, the plane proved to heavy for the Air Observation Post squadrons at 3,325 gross pounds, besides being more expensive that the L-4. The L-1 found a home in the CBI Theater, with its power plant able to hoist the plane over some of the mountains in-theater and able to effect medical evacuations and light-transport duty.

Transporting of wounded became virtually a matter of life or death in the impenetrable jungle. Backwater hospitals were linked by light planes making repeated runs to and from combat zones, airlifting foot sloggers in need of doctor’s care. The rudiment of the later Dustoff squadron in Vietnam can be found in the CBI. And examples abound:

“In response to a desperate plea for help from a big British force trapped in the Arakon area of southern Burma, seven light planes and nineteen sergeant pilots in fifteen days evacuated seven hundred casualties—with British Spitfires flying cover.[10]

OSS member, Richard Dunlop, related a rescue of a B-25 crew that had crashed into a swamp some 20 miles north of Myitkyina, ” . . . and Dennis Francis and a party of Kachins hurried to the scene from Arang. They found the crew alive but in terrible condition. There was no possibility that they could survive a trip by surface over the Mogaung Valley’s precipitous trails, so Francis and the Kachins hastily leveled a meager three-hundred-foot-long airfield in the patties . . . and a liaison pilot named Anderson flew his two-seater L-1 in from Myitkyina to pick up the injured fliers. He made five trips, a trip for each man, bringing them all out to Myitkyina from where they could be flown to the hospital in Ledo.[11]

Yet whether in or out of the CBI, it was not all doom and gloom in the PTO; there was a lighter side, even in that giant whirlpool of war. “General Joseph ‘Vinegar Joe’ Stilwell, Commander of Tenth Army, used Cubs extensively during operations in the Pacific. He enjoyed riding with the Air OPs with the windows open. On one occasion he was being flown by SSgt. Lyle W. White on a mission off Okinawa. A gust of wind blew through the Cub’s cockpit and the general’s battered campaign hat that he had worn for over 20 years, blew out the window.

“General Stilwell sadly watched his hat float down and plop into the sea. He remarked, ‘I’d sure like to go down there and rescue my old friend.’ Upon landing, Stilwell offered $25 to anyone who recovered the hat; much to his delight, it was returned to him 4 hours later.”[12]

Postscript

This is the sixth and final chapter of the “80th Anniversary of Army Aviation in World War II —or what it really was, the Air Observation Post. Reference to the entire series can be found rostered in endnote number 13.[13]

On December 8th, 1941, the Air OP’s sole reason for existence was for the aerial direction of artillery fire. And the platform of choice was the L-4 Piper Cub, an aircraft which appears in the annals of Army Aviation and, which can be construed as having changed the course of the history of the tactical air branch of the United States Army. The first being the gas bags of the Balloon Corps followed by the Cub; succeeded by the UH-1 Huey, which in turn will be followed by the AH-64 Apache. Each is emblematic of the distinct phases which mark the Saga of Army Aviation.

The ubiquitous Cub was the Air OP’s plane of World War II. Inexpensive, easy to maintain and fix, able to operate from unpaved strips near the front, the versatile Cub proved able to perform a variety of labors, including its primary task, the aerial direction of artillery fire. Served in both World War II and Korea. Piper’s Cub as that second aircraft in the development and evolution of Army Aviation. Shown here are a pair of Cubs operating off a jungle strip in the Pacific.

The gas bags of the Balloon Corps marked the Army’s first organized attempt into the realm of airpower, predominately for the purposes of aerial reconnaissance followed by modest attempts at the aerial direction of artillery fire. But the tethered balloon embodied the lack of mobility during the first half of the War Between the States; precisely the factor which would justify the comeback of the static balloon some fifty years later on the Western Front. But with the advent of mobility returning to the battlefield in 1863, Union generals steeped in the Napoleonic-Jomini tradition of arms relied on swift moving cavalry formations to conduct reconnaissance as well as maneuver warfare.

The Balloon Corps was the Army’s first sojourn into ‘airpower.’ Tethered balloons were utilized for aerial reconnaissance and the early attempts at the aerial direction of artillery fire. As the Union Army took control of the war by 1863 and mobility was becoming decisive, the labor-intensive balloons were seen as an impediment by the more reactionary of the officer class. Cavalry was still seen as that arm of reconnaissance and shock. Yet the seeds for the future were being planted, 1861-1863. Lowe’s balloons must be seen as the first aircraft in that evolution in the development of tactical aviation in the United States Army that will eventually result in the Air Observation Post, which will become Army Aviation itself. Pictured is Thaddeus Lowe going up in a balloon during the Battle of Seven Pines, June 1, 1862.

The L-4 Cub, though, provided that mode of mobility needed for the Field Artillery to effect the aerial direction of artillery fire within the confines of modern conventional warfare. Easy to maintain and cheap to manufacture, the Cub represented that vehicle of mobility that would form the basis for a tactical air capability for the Ground Forces, a giant step forward. For it was almost certain as sunrise that with the advent of the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1941, and the wider field of opportunity that was provided for the strategic employment of airpower during World War II, that a separate branch known as the United States Air Force was a foregone conclusion.

So to for the Ground Forces. The Air OPs proved their worth to the extent that other branches of the Army desired their services or clamored for their own capabilities, such as the Infantry and Armor. For besides directing artillery fire, Air OPs conduced aerial observation, aerial photography, route-column control, cabbie service for brass, medical evacuation, courier service, light conveyance of supplies, as well as directing attack aircraft and fighter-bombers in strikes against ground targets. “’The effectiveness of air-ground cooperation is still in its infancy. Air and ground commanders must be constantly on the alert to devise, and use, new methods of cooperation.’ These words, written by General George S. Patton, Jr., in 1945 and published in his book, War as I Knew it, are still worth our attention.”[14]

Yet a major contributor to the future course of Army Aviation were those actions taken by those inspired to arm their Cubs for combat. Enterprising individuals looking to turn their putt-putts into war machines . . . that is, of a sort, firing .45s out of the cockpit or affixing bazookas and even missiles to the wings. In Italy, for instance, Cubs from the Fifth Army were prepped to launch a bombing raid. “With all systems go, the attacking L-4s putt-putted up to the green Auscente Valley in their usual lackadaisical manner, then suddenly they shifted direction and raced, with what for them was phenomenal speed, over the target area. Each pilot carried a five-gallon tin can of gasoline mixed with oil on his wing strut and at the precise moment, he shoved it off with his foot. Most of the ‘bombs’ landed well outside the target area.”[15]

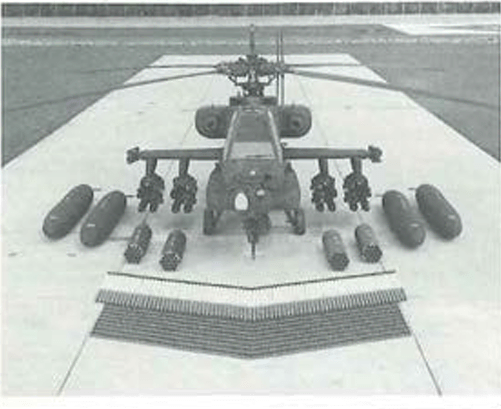

The AH-64 Apache attack helicopter. The fourth aircraft that made Army Aviation what it is. The Apache is a lethal aircraft able to support the ground soldier as well as being effective against enemy armor.

The arming of Cubs for action against the enemy amounted to little better than mosquitoes attacking an elephant. But such episodes of individual initiative were hardly examples of comic relief; rather, these efforts were examples of Yankee ingenuity and independent thinking (usually frowned upon by reactionary types). For in the end, perhaps the arming of Cubs displayed a deep-seated distrust of the Air Force agenda. And for those ready to disparage such thoughts need to be mindful of the actions taken by “Vanderpool’s Fools,” 11 or 12 years down the road. This, then, should make it obvious that not only were the airmen in the Army Air Forces looking to create an independent service, but the seeds were being planted for an autonomous aviation branch within the Army to take its place alongside the Infantry, Armor, Signal Corps, etc. The first attempt to create something resembling autonomy for airpower was in 1914, with the actions of Lieutenant Paul Beck and Congressman James Hay; though it was reaching critical mass by 1945.[16] And by 1947, with the National Security Act, the U.S. Air Force took it place alongside the Army and Navy as a separate service. But differences of opinion concerning roles and missions would not end with the divorce from the Army. And as with many broken marriages, disagreements continued for years. Hence the use of Cubs for the evacuation of wounded or to pick up and drop off personnel, which accurately forecast the Army’s use of the Huey to perform the same tasks on a more massive scale in Vietnam; as did the arming of the Cubs showcase the future employment of the AH-64 Apache by the Army to handle its version of close air support of the foot soldier. Classic examples of how history repeats; of course, the repetition is never exact, but it does repeat. Or if you are a disciple of Mark Twain, history rhymes.

The third of the decisive aircraft in the history of Army Aviation, the UH-1 Huey, the workhorse of the Airmobility Concept during the Vietnam War.

It is undeniable that the actions of the Air OPs to competently perform tasks other than that of the aerial direction of artillery fire broadened the appeal of Army Aviation; an appeal that would serve to bolster the post-World War II fortunes of Army Aviation . . . an appeal that would be advanced by the helicopter.

We begin with the Sikorsky VS-316, a platform based off the VS-300 prototype. A contract was signed with the Army Air Corps on January 10, 1941. And the VS-316, better known as the R-4, became acknowledged as the world’s first production helicopter.

On May 13, 1942, test pilot Les Morris took off from Bridgeport, Connecticut for a long distance flight to Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio. “The trip took five days and covered 761 miles. The elapsed time was 16 hours and 10 minutes in a series of 16 separate flights. A ‘chase’ vehicle (a sedan with 4 passengers) . . . with a large yellow circle painted on the roof accompanied the XR-4. Igor Sikorsky flew with . . . Les Morris from Cleveland to Mansfield, Ohio and the final leg from Springfield to Dayton, Ohio. The XR-4 arrived in Dayton on May 17, 1942 and was accepted by the Government on May 30, 1942. During the trip two unofficial records wee set: A distance record of 92 miles (Mansfield to Springfield) and an endurance record of one hour and 50 minutes.”[17]

Igor Sikorsky, with Coast Guard Commander Frank Erickson at the controls of a Sikorsky R-4 helicopter, August 1944. The R-4 was the first true production helicopter. Little used in World War II, the helicopter will find acceptance during the Korean War. It will be during the Vietnam conflict that the Bell UH-1 Huey will become the workhorse of the Airmobility Concept and therefore, become that third aircraft most important in the ongoing evolution of Army Aviation.

Captain Frank Gregory, USAAF, who was responsible for helicopter development for the Army, conducted shipboard tests from the tanker, Bunker Hill, in Long Island Sound off Stratford, Connecticut. Twenty successful liftoffs by Captain Gregory showcased the potential maritime utility of rotary wing aircraft.[18]

The first actual combat rescue mission was flown by 2nd Lieutenant Carter Harmon, USAAF, April 26-27, 1944. Behind enemy lines in Burma, were three wounded British commandos and the USAAF pilot sent to effect their rescue, all left stranded when their L-1 had gone down in the jungle. Liaison planes kept the men supplied for four nights. Harmon, meanwhile, had removed the co-pilot’s seat from his YR-4 so as to accommodate four Jerry cans for another 21 gallons of fuel. He took off from Lalagat, India, flying a route which included scaling a 6,000 foot mountain range. He made four trips to extract those trapped.[19]

The shades of Vietnam here are unmistakable. And the actions of such groups as the 71st Liaison Squadron and the 1st Air Commando Group commanded by Colonels Phil Cochran and

John Alison, forecast the Army’s performance in Southeast Asia twenty years hence. But instead of the flivver plane, it would be the helicopter that would carry the ball for the Army. The old saying is that you have to crawl before you can walk. Well in World War II, the helicopter was crawling; in Korea, it walked. But in Vietnam, the helicopter ran—fast . . . proving a concept that would revolutionize warfare, the Airmobility Concept; a game-changing notion akin to the Wehrmacht’s use of the armored warfare fighting vehicle in a Combined Arms Warfare package that ensured the quick destruction of Germany’s enemies; AKA Blitzkrieg, which proved a vindication of the interwar understanding of the ghastly stalemate of the trenches during 1914-1918, by such theorists as Hans von Seeckt. Likewise, the Airmobility Concept was a vindication of lessons learned during the bloody impasse on the Korean Peninsula.

But it behooves those intimately affiliated with Army Aviation to not only understand their history at this stage, but to thoroughly comprehend it. For Army Aviation is not only a branch of the Army—a one-dimensional exercise in reflection practiced by those who are but of a narrow-minded variety. Rather Army Aviation is an experience, an emotion. We need to celebrate those stalwart types who emerged from World War II and Korea to weather a storm of criticism based on a stigma accepted by short-sighted brother soldiers who chided them for sticking with a segment of the Service which was viewed as nothing more than a dead end. Talk to a few Cub pilots and early helicopter jockeys and that is exactly what they will tell you. The success of Army Aviation, then, was built on those who refused to capitulate to such reactionary thinking and antagonisms. This, then, makes Army Aviation not merely a branch of the United States Army, but . . . a Movement. A movement like the 19th century Carbonari who were wedded to the Il Risorgimento or Unification of Italy. Like the Vietminh led by Ho Chi Minh who fought and later won the unification of Vietnam. Like the United States Marine Corps. Leathernecks, it seems, are not just Veterans or active duty people. They are part of a tradition that is a Brotherhood, one which goes back to the American Revolution, with each generation adding and building that tradition. The Royal Navy can be viewed along similar lines. And that is how Army Aviation must be viewed by its veterans and supporters, such as those of the Army Aviation Association of America. A poverty of such attitude and Army Aviation will not be long for this world. And it is with this idea in mind that this series is dedicated to those early aviators in both Cubs and helicopters, together with their ground crews and all those others who organized the Air Observation Post and its evolution into what is today’s Army Aviation. For without their steadfast perseverance, Army Aviation never would have become that indispensable vehicle of support of the Foot Soldier.

Endnotes

[1] See page 467, Chapter 21, “Grand Strategy and the Washington High Command,” American Military History, edited by Maurice Matloff.

[2] For the invasion of Leyte, October 1944, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger had 202,500 troops in his Sixth Army. See page 10, “Operations,” Leyte, The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II, United States Army Center of Military History, by Charles R. Anderson.

For the invasion of Okinawa, April 1, 1945, Lieutenant General Simon B. Buckner, in command of Tenth Army, had 183,000 soldiers and marines. See pages 21-28, Chapter 1, “Operation Iceberg,” Okinawa: The Last Battle, by Roy E. Appleman, James M. Burns, Russell A. Gugeler and John Stevens.

[3] See page 253, “The Field Artillery Observation Battalion,” Prepared in the Department of Observation, the Artillery School, The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 38, No. 6. December 1948.

[4] See page 279, “Air OPs . . . in New Guinea,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 34, No. 5, May 1944, by Captain Robert M. White, II, F.A.

[5] See page 280, Captain Robert M. White, II, F.A.

[6] See pages 614-616, “Artillery Cubs in Mountain Operations: 33rd Inf. Div. in Northern Luzon,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 35, No. 10, October 1945, by Colonel Ralph MacDonald, F.A.

[7] See page 73, “Biscuit Bombers (Leyte Style),” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 38, No. 2, March-April, 1948, by Major Edward M. Flanagan, Jr., F.A.

[8] “The Operations of the 3rd Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry (11th Airborne Division) in the Advance Through the Mohonag-Anas Pass to the West Coast of Leyte, 27 November-25 December 1944,” 1st Lieutenant Richard V. Barnum, Advanced Infantry Officers Class No. II, Fort Benning, GA.

[9] See page 93, Chapter 4, “Employment,” The Development of Organic Light Aviation in the Army Ground Forces in World War II, by Major Robert S. Brown, USA.

[10] See page 115, “The Most Lethal Plane in the World,” Mr. Piper and His Cubs, by Devon Francis.

[11] See pages 308 and 309, “The Airport,” Behind the Lines: With the OSS in Burma, by Richard Dunlop.

[12] See page 170, Chapter IV, “The War Years: Europe, Pacific and Korea,” The Army Aviation Story, by Richard K. Tierney with Fred Montgomery.

[13] Below is a listing of the six articles chronicling the Air Observation Post in World War II:

1) “80th Anniversary of Army Aviation: Reflections in North Africa,” Looking Back column, August 2022.

2) “80th Anniversary of Army Aviation: Combat Debut: Operation: TORCH,” Looking Back column, November 2022.

3: “80th Anniversary of Army Aviation: Operation: TORCH: Grasshoppers Earn Their Wings,” Looking Back column, December 2022.

4) “80th Anniversary of World War II: Army Aviation: Italian Campaign,” Looking Back column, September 2023.

5) “80th Anniversary of World War II: Army Aviation: France,” Looking Back column, August 2024.

6) “80th Anniversary of World War II: Army Aviation: The Pacific Theater,” Looking Back column, May 2025.

[14] See page 169, “Artillery in Air-Ground Cooperation,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 38, No. 4, July-August 1948, by Lieutenant Colonel Edward S. Berry, F.A.

[15] See page 66 and 69, Chapter Seven, “Sunny Italy,” Box Seat Over Hell, by Hardy D. Cannon.

[16] Pages 18 and 19, Chapter Two, “Needle-Point Air Force,” Sky Soldiers: The Saga of Army Aviation, Vol. 1, by Mark Albertson. Unpublished manuscript.

[17] See page 5, “S-47/VS-316A Helicopter,” Sikorsky Product History, prepared by Vinny Devine.

[18] See pages 6 and 7, “The Development of the Helicopter,” Sikorsky Historical Archives, www.sikorskyarchives.com/tdoth.html

[19] See page 9, Vinny Devine. Consult, too, “Saga of the Eggbeater,” by Mark Albertson, World War II History, pages 8-11, 74, October 2016.

Bibliography

Albertson, Mark, “Saga of the Eggbeater,” World War II History, Sovereign Media, McLean, Virginia, October 2016.

Albertson, Mark, unpublished manuscript, Vol. 1, Sky Soldiers: The Saga of Army Aviation.

Anderson, Charles R., Leyte, 17 October 1944 to 1 July 1945, U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II, Center of Military History, United States Army, CMH Pub 72-27, Washington, D.C., 1994.

Appleman, Roy E.; Burns, James M.; Gugeler, Russell A. and Stevens, John, Okinawa: The Last Battle, World War II, 50th Commemorative Edition, Center of Military History, United States Army, CMH Pub 5-11-1, Washington, D.C., 1993. First published 1948.

Barnum, 1st Lieutenant Richard V., Advanced Officers Class No. 11, Fort Benning, Georgia, “The Operations of the 3rd Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry (11th Airborne Division), in the Advance Through the Mohonag-Anas Pass to the West Coast of Leyte, 27 November-25 December 1944.”

Berry, Lieutenant Colonel Edward S., F.A., “Artillery in Air-Ground Cooperation,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 38, No. 4, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., July-August, 1948.

Brown, Major, Robert S., The Development of Organic Light Aviation in the Army Ground Forces in World War II, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, June 2, 2000.

Cannon, Hardy D., Box Seat Over Hell, Hardy Cannon, San Antonio, Texas, 1985.

Department of Observation, The Artillery School, “The Field Artillery Observation Battalion,” Vol. 38, No. 6, The Field Artillery Journal, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., December, 1948.

Devine, Vinny, “S-47/VS-316A Helicopter,” Sikorsky Product History, Igor I. Sikorsky Archives, sikorskyarchives.com/home/sikorsky-product

Dunlop, Richard, Behind the Lines: With the OSS in Burma, Rand McNally & Company, Chicago, New York, San Francisco, 1979.

Flanagan, Major Edward M., Jr., F.A., “Biscuit Bombers (Leyte Style),” Vol. 38, No. 2, The Field Artillery Journal, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., March-April, 1948.

Francis, Devon, Mr. Piper and His Cubs, The Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1973.

MacDonald, Colonel Ralph, F.A., “Artillery Cubs in Mountain Operations: 33rd Inf. Div. in Northern Luzon,” Vol. 35, No. 10, The Field Artillery Journal, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., October 1945.

Matloff, Maurice, General Editor, American Military History, Army Historical Series, Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1969.

“The Development of the Helicopter,” Sikorsky Product History, Igor I. Sikorsky Archives, www.sikorskyarchives.com/tdoth.html

Tierney, Richard with Montgomery, Fred, The Army Aviation Story, Colonial Press, Northport, Alabama, 1963.

White, Captain Robert M., F.A., “Air OPs . . . in New Guinea,” Vol. 34, No. 5, The Field Artillery Journal, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., May, 1944.

Looking Back, April 2025

By Mark Albertson

Operation: KIKUSUI

* * * * *

“We are 16 warriors manning the bombers. May our death be as sudden as the shattering of glass, . . . from the letter of a Kamikaze pilot.”[2]

* * * * *

It was 80 years ago, April 1, 1945, that Operation: ICEBERG commenced. GIs and marines waded ashore to nary the expected opposition, unlike at Tarawa, Saipan, Guam, Peleliu and a half a hundred other places. The marines struck out for the northern half of the island, encountering light resistance; while the Army, moving south, too, faced light resistance. Suddenly the Army ran up against a wall of fanatical Japanese who were well dug in. Casualties mounted quickly. Up north, the leathernecks reversed course and hurried south to assist their brother soldiers. They, too, began to incur heavy losses on the Shuri Line.

Soon the battle of Okinawa, the final major battle of World War II would, in just eight weeks, become the third costliest battle in American history.[3]

Yet while the marines and soldiers ashore waged the bitter struggle against the seemingly impregnable Shuri Line, the Navy trying to command the seas around the embattled island will incur its worst losses of the war. For the Japanese will unleash its most frightening weapon of the conflict, the Devine Wind or Kamikaze. The origins of which are steeped in history.

“A hurricane swept the invasion fleet of Kublai Khan to disaster off the Japanese coast in 1281. That ‘devine wind’ saved the Japanese people from foreign domination. In the last years of World War II, with the tide of Imperial Japanese expansion beaten back, a similar intervention was needed to save Japan from subjection.”[4]

By well into 1943, when it was apparent the tide was turning in the Pacific Theater, the Japanese began to consider approaches other than those of the standard varieties of waging war in an attempt to halt the growing American juggernaut. Ramming attacks (taiatari) were employed against American aircraft. Origins here go back to the Bougainville campaign, November 1943, when ramming was used by frustrated Navy pilots.[5]

An example of the above was that of Lieutenant Naoshi Kanno, 306th Fighter Squadron, 201st Air Group, 1944, based on Yap. Kanno took on a B-24. He made a head-on approach, only to find his guns were jammed. He rapidly closed his quarry, only to sheer away at the last moment, nearly brushing the bomber, only to use his propeller to cut up one on the B-24’s vertical stabilizers. The Liberator plunged into the sea. Kanno, meanwhile, nursed his sputtering Zero back to Yap.[6]

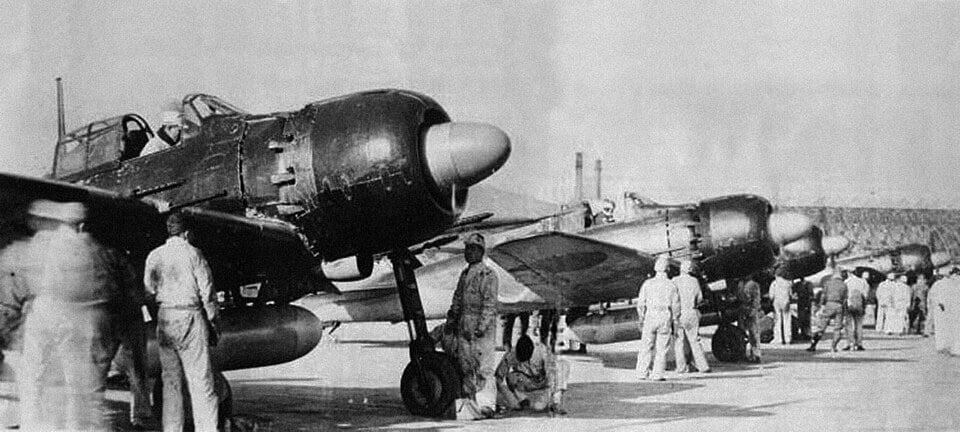

The legendary Mitsubishi Zero fighter. Once the world’s dominate carrier fighter, was by the latter stages of the war overtaken by such types as the F6F Hellcat, F4U Corsair and P-51 Mustang. The Zero, though, will be seen as the premier plane for the Special Attack Corps. Total wartime production of the A6M Zero, 10,611 machines. Does not count the 327 Rufe float Zero type.

But ramming enemy aircraft was hardly a war-winning tactic. Besides, there was certainly the chance that to bring down an enemy aircraft by ramming could cost a Japanese aircraft and perhaps even the pilot. Something, then, of greater impact was called for. Something that could cause the enemy such grievous losses, while at the same time reverse Japanese fortunes.

* * * * *

One of the early supporters of suicide as a military tactic was Captain Eiichiro Jyo, commander of the light carrier Chiyoda. In the wake of the American victory in the Philippine Sea, Captain Jyo observed, “No longer can we hope to sink the numerically superior enemy aircraft carriers through ordinary attack methods. I urge the immediate organization of special attack units to carry out crash-dive tactics, and I ask to be placed in command of them.”[7]

Yet the Japanese were fully aware that the United States was going to invade the Philippines and, with the ever growing might of American naval power, extraordinary alternatives to successfully challenge said threat had to be considered.

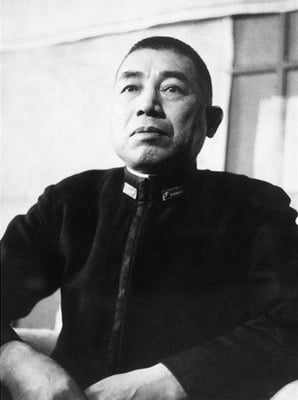

Admiral Takijiro Ohnishi, organizer of the Special Attack Corps or Kamikaze, the Devine Wind. Upon the Japanese surrender, he will commit ritual suicide, August 15, 1945, as atonement for failure and the loss of so many young men in the Kamikaze Corps.

October 17, 1944, Vice Admiral Takajiro Ohnishi arrived in Manila to take command of First Air Fleet. He convened a meeting in Mabalacat, headquarters of the 201st Air Group. Addressing a small collection of air officers, he spoke of the upcoming naval battle for the Philippines and the Imperial Japanese Navy’s growing disparity against the material advantage enjoyed by its Occidental opponent.

“In my opinion,” he continued, “there is only one way of assuring that our meager strength will be effective to a maximum degree. That is to organize suicide attack units composed of Zero fighters armed with 250 kilogram bombs, with each plane to crash-dive into enemy carriers, . . . what do you think?[8]

After a round of discussions as to how effective such a drastic action might be, Commander Assaichi Tamai was ordered to form, what would become the first squadron of the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps. The pilot assigned to lead the first attack was Lieutenant Yukio Seki. Admiral Ohnishi will sign an announcement for the new Attack Corps on October 20, 1944.

Lieutenant Yukio Seki, leads the first successful Kamikaze flight against the American amphibious forces off Samar. Leader of Shikishima flight, he crashed his Zero into the escort carrier St. Lo and sinks same.

“The 201st Air Group will organize a special attack corps and will destroy or disable, if possible by 25 October, the enemy carrier forces in the waters east of the Philippines.

Kamikaze pilots of the 201st Naval Air Group, at Mabalacat, the Philippines. The photo is reputed to be the ill-fated Shikishima flight. The pilot drinking the sake is supposed to be Lieutenant Yukio Seki, man who sinks the St. Lo. The man to the left, with his back to the camera, is supposed to be Assaichi Tamai, Seki’s immediate commander. October 25, 1944.

“The corps will be called the Shimpu Attack Unit. It will consist of 26 fighter planes, of which half will be assigned to crash-diving missions, and the remainder to escort, and will be divided into four sections, designated as follows: Shikishima, Yamato, Asahi and Yamazakura.”[9]

* * * * *

As the Kamikazes were readying themselves for devine self-immolation, history’s greatest naval battle, Leyte Gulf, had already commenced. This was the last major attempt by the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet to change the momentum of the naval war and turn back the American threat to Japan’s inner defense ring. The basic Japanese plan saw Southern Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Shojo Nishimura with 2 battleships, 3 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser and 7 destroyers come up from the south of Leyte Gulf from the Mindanao Sea through the Surigau Strait to attack the American landing forces of light carriers, destroyers and support vessels; and then from the north, Vice Admiral Takao Kurita, with 5 battleships, 10 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers and 15 destroyers would slip through the San Bernadino Strait, round Samar, then attack the light American landing forces at Leyte from the north. Japanese carriers north of the Philippines had successfully drew Admiral William Halsey’s covering force of carriers and battleships north, leaving the light amphibious forces off Leyte without protection.

Admiral Jessie Oldendorf’s task force of old battleships backed by cruisers devastated Nishimura’s southern force in the confined waters of the Surigao Strait, denying the Japanese their southern pincer in their attempt to wipe out the American landing forces. However, Admiral Kurita did round Samar to keep his appointment.

The American naval response consisting of destroyers and destroyer escorts against the big boys of the IJN became one of the stirring acts of heroism of the entire war in the Pacific, sometimes referred to as their Death Ride; in addition to which the pilots of the beleaguered escort carriers attacked like angry hornets against battleships and cruisers, even to the dropping of depth charges in lieu of bombs. Kurita will fail in his mission and eventually withdrawal. This threat will subside; but it will give way to an even greater threat, the Devine Wind.

* * * * *

October 21, 1944, Lieutenant Seki led his flight from Mabalacat to search for the reported American escort carriers off the Philippine coast. No trace was found and the flight returned to base. Then more flights, October 22, 23, and 24, again resulted in no-shows. On the 25th, though, they struck pay dirt.

Nine Zeros, four of which were escorts, had flown 3 hours and 25 minutes before they found the American escort carriers off Samar. They had made their approach as Admiral Ohnishi had suggested: Low, wave-hopping, so as to approach below the Americans’ radar. Then they climbed to their attack altitude so as to take their final plunge.

The stricken escort carrier, St. Lo, explodes after being hit by Lieutenant Seki and his Zero. Eight explosions will wrack the flattop before she took the final plunge, off Samar, October 25, 1944.

Shikishima flight of five suicide planes pushed over into attack. Flight leader Yukio Seki dove for the St Lo. Through a hail of anti-aircraft fire he plunged, undaunted. As he closed the flattop, he released his 550-pound bomb. It immediately pierced the flight deck, into the hanger deck and there exploded, cascading the elevator upwards and sending up a geyser of planes and parts; into which Seki’s Zero piled into the fiery carnage. Eight explosions ensued, tearing the baby flattop apart. An hour later St. Lo took the plunge.

Another suicide pilot closed the Kitkun Bay, strafing as he bore in. His target was the bridge, missed, zoomed over, caught the catwalk then crashed into the sea. His 550-pound bomb detonated, showering the Kitkun Bay with fragments, wounding and maiming bluejackets.

Then a pair of Kamikazes targeted Fanshaw Bay, only to be splashed by the carrier’s hot gunners.

Shikishima flight died to a man. But this did not mark the end of the attacks, for 15 dive-bombers pushed over into their death-dives. Fighters that had harried Kurita’s fleet now were vectored in to defend the carriers from this new threat. The aforementioned Kitkun Bay threw up two more fighters as well. The carrier had survived Kurita, but now came a new threat.

A Val dove for the flattop, aiming for the flight deck. The carrier’s gunners threw up withering fire. The wings of the plane came off, leaving the fuselage to pile into the sea, narrowly missing the carrier, showering her deck with fragments and plane parts.

Kalinin Bay was not so fortunate. A Kamikaze, seemingly impervious to the flattop’s gunnery crashed into the flight deck, doing grievous damage here and causing many casualties. But carrier’s plight continued as a second suicide pilot crashed into the after smokestack. Kalinin Bay, though punch drunk, survived.[10]

The four escorting Zeros of Shikishima flight-losing one after tangling with American fighters—returned to base to report the results. One American escort carrier sunk, with at least five others damaged.[11] The Kamikaze had proven itself on the field of battle. It was here to stay.

* * * * *

The Kamikaze was accepted as a tactic in response to a daunting reality: The standard methods of naval air warfare such a dive-bombing and torpedo attacks were no longer successful. This, owing in part, to the superiority of the newer American fighter planes such as the F6F Hellcat, F4U Corsair and the P-51 Mustang. In addition to the fact of superior American production, with earlier losses in warships not only replaced, but providing the United States with an unchallengeable two-ocean navy.

In the face of the above, Japanese aircraft such as the Aichi D3 Val dive-bomber with its fixed landing gear, the B3N Kate torpedo bomber had seen better days and had lost their superiority to the American Helldiver and Avenger torpedo plane. The famous Zero fighter, though still speedy and nimble, had lost its superiority to the new American fighter types. Yet it was still regarded as that plane best able to breech American defenses and cause that carnage necessary to reverse Japan’s fortunes.

Dated March 1945, an 88-page manual had been prepared by the Shimoshizu Air Unit, Chiba Prefecture, not far from Tokyo. Bearing the name of the unit commander, a Major Hayashino, it was a how-to for Kamikaze pilots. Actual title, Basic Instruction to To-Go Flyers. (To-Go was the codename for Special Attack Corps.)[12]

“Where to Crash, the Enemy’s Fatal Spots”

“Where should you aim? When diving and crashing onto a ship, aim for a point between the bridge tower and the smoke stack(s). Entering the stack is also effective. Avoid hitting the bridge tower or a gun turret. In the case of an aircraft carrier, aim at the elevators. Or if that is difficult, hit the flight deck at the ship’s stern. For a low horizontal attack, aim at the middle of the vessel, slightly higher than the waterline. If that is difficult, in the case of an aircraft carrier, aim at the entrance to the aircraft hangar or the bottom of the stack. For all other vessels, aim close to the aft engine room.”[13]

“You Are Now 30 Meters From the Target.”

“You will sense that your speed will suddenly and abruptly increase. You feel that the speed has increased by a few thousand fold. It is the long shot movie suddenly turning into a close-up and the sense expands in your face.”

“The Moment of the Crash”

“You are two or three meters from the target. You can see clearly the muzzles of the enemy’s guns. You feel that you are suddenly floating in the air. At that moment, you see your mother’s face. She is not smiling or crying. It is her usual face.”[14]

* * * * *

“The nature of the threat was self-evident, need for what was called ‘special’ measures of the highest degree of sacrifice was clear. The Chief of Staff informed the Emperor about the provisions for Kamikaze operations, which had already begun in a preliminary way, against the American fleet engaged in the bombardment (at Okinawa). The Emperor urged Admiral Koshiro Oikawa to ‘leave nothing to be desired’ in executing those plans ‘with a hard struggle by all our forces, since [they] will decide the fate of our Empire.’ Oikawa’s assurance that two thousand planes were available for suicide attacks left Hirohito clearly concerned. ‘Was that all?’ he asked, in his reedy, high-pitched voice. The admiral’s hasty reply that the Army would contribute an additional fifteen hundred aircraft did not dispel His Majesty’s puzzlement. ‘But where is the Navy?’ he asked, his tone putting an edge to the question. ‘Are there no more ships? No surface forces?’”[15] This exchange occurred in March 1945.

Thus far, since the Kamikazes had been employed, beginning with the actions off Samar to the attacks on the U.S. fleet in the Lingayen Gulf: “Between October 25, 1944, when the Kamikaze pilots made their first successful attack, and January 25, 1945, we estimated that our suicide pilots inflicted from light to severe damage to at least fifty American vessels of all types. These included six large aircraft carriers, four of which were identified as the Intrepid, Franklin, Essex and Lexington; the two small aircraft carriers Belleau Wood and Independence; and the escort carrier St. Lo. It was impossible at the time, of course, to determine specifically the names of these carriers our planes had struck such as the Santee, Suwannee, etc., until corroboration could be received through American reports. Confirmation by our escorting Zero fighters was at best a questionable affair, because of the speed of the attacks, the fierce fighter and anti-aircraft defenses, and the abort period over the target area.”[16]

January 18, 1945, the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War made official government policy of, Admiral Ohnishi’s Special Attack Corps. “The Council decided to ‘concentrate on converting all armament production to special attack weapons of a few major types.’ The available weapons systems were reduced to a suicide arsenal that included special submarines of the Koryu and Kaiyu class, high-speed small boats of the Shinyo class which exploded upon contact with enemy ships, and the Kaiten human torpedo. The army’s contribution was a human bomb: a soldier wrapped in explosives who hurled himself against an enemy tank, blowing it and himself to bits. A military psychology insensitive to human life, to the individual’s right to survive, conceived the Special Attack idea. The same mentality underlay the policy of requiring Japanese soldiers taken prisoner, even if they managed to return to friendly lines, to commit suicide.”[17]

Okinawa

Special Attack Corps operations were unleashed against the 5th Fleet supporting the marines and GIs ashore. 355 Kikusuis swarmed 5th Fleet, in addition to conventional dive-bombing and torpedo attacks. In two days, April 6 and 7, 19 ships were damaged.

Again the optimum targets were the carriers, especially with disabling same by crashing into the elevators. A flattop unable to utilize its air complement was little better than a target. Other targets of opportunity were support vessels, supply ships, troop transports, . . . On April 1, a Kamikaze struck the transport Alpine, killing 16 and wounding 27. Another transport, Achernar, was both bombed and crashed by a Kamikaze, leaving 8 killed and 41 wounded.[18]

Undamaged cargos were unloaded leaving both ships to retire from the scene for repairs.

On April 3, the escort carrier, Wake Island, faced off with five planes coming in from her starboard quarter. Two diving for her missed, splashing near the flattop. The second, though, exploded, tearing a hole 18 by 45 feet into Wake Island’s hull. It was back to Guam for repairs.

To shield 5th Fleet from attack and act as an early warning system, destroyers were assigned, along the lines of Britain’s radar stations that acted as that early warning system for RAF squadrons during the battle of Britain. Yet despite the mobility of the American system, these picket destroyers and the bluejackets who manned them must be remembered for their courage and heroism for their part in the Plight of the Pickets.

Plight of the Pickets

March 24, 1945, USS Mannert L. Abele (DD-733), an Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer, began the campaign with the preliminary bombardments of Okinawa. By April 12, DD-733 was on picket duty, Station No. 4, some 70 miles northwest of Okinawa.

At 1445 hours, a trio of dive-bombers popped out of the clouds. Pilots pushed over into their death dives. Ablele’s gunners threw up a cloud of A.A. Two of the intruders were flamed. The third, too, was hit, then plunged into the sea.

Then, three more, this time Zeros. Two were quickly splashed. The third Zeke, bracketed by 40 mm and 20 mm and the 5-inch main batteries, was soon hit. Pieces flew back into the slipstream. Flames and black smoke marked the pilot’s path to imperial heaven.

But the gunners could not prevent the Zero’s appointed rendezvous and it crashed into the starboard side, just aft of Abele’s no. 2 stack. The Zero’s bomb pierced the main deck, exploded in the after engine room, rupturing the can’s keel, wrecking the propeller shaft, killing nine men.

Then, in quick succession, skimming the sea, sped a Baka Bomb. The piloted cigar tube was closing the can at upwards of 500 mph. Gunners furiously targeted the missile, but to no avail, as it knifed into the forward fireroom, killing and wounding bluejackets, violently shaking the ship and breaking the keel yet again.

MXY7-KI Ohka or Oka, meaning “Cherry Blossom.” Many Allied military personnel preferred “Baka” meaning idiot or dumb. A manned rocket which could hit upwards of 500 mph, designed to crash into enemy ships. Usually carried by a mother plane to its assigned launch point. Such a plane was the Mitsubishi G4M medium bomber, known to the Allies as the “Betty.” As a bomber, the twin-engine Betty had a great range, some 2,262 miles. But this came at the expense of armor for the crew and fuel tanks.

The stricken DD began to settle. Commander A.E. Parker ordered the crew to the boats. Eighty-two of his crew were dead, 32 more were wounded. All together 336 were rescued.

The Abele broke in two, then disappeared beneath the waves.

* * * * *

April 16, 1945: Radar Picket Station No. 1, off Okinawa

On duty here was USS Laffey (DD-724), another Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer. Skipper was Commander Frederick J. Becton. Laffey will go down in American history as one of the most damaged of warships, certainly of destroyers and, . . . fortunately, Becton and many of his crew will live to tell the tale.

In concert with DD-724 was a pair of Landing Craft Support vessels, LCS-51 and LCS-116. These “were adaptations of Landing Craft Infantry armed with .50-caliber, 20 mm and 40 mm guns. Slow—a top speed of 16 knots—shallow-bottomed and squat—160 feet long, with a 23-foot beam—the ungainly LCS’s chief merit was versatility.

“Two high-capacity pumps enabled the gunboat to double as a fireboat. Young LCS skippers like the 51’s Lieutenant Howell D. Chickering and the 116’s Lieutenant A.J. Wierzbicki had few illusions about their purpose. After suicide attacks, they would be dousing fires, removing casualties, and recovering survivors.”[19]

0827, the radar operator’s screen was aglow with fifty enemy aircraft, all approaching from the north. The stage was now set for the next eighty minutes, the battle for survival began.

Laffey’s fire direction officer urged the area’s combat air patrol to steer clear of the can’s anti-aircraft fire.

On closing the Laffey, Kamikazes came in from every point on the compass. The aim was to not only split the gunnery, but overwhelm it. Indeed, officers aboard Laffey will note 22 attacks.

The battle began when four Aichi D3A Val dive-bombers targeted Laffey. Two bore in from the starboard bow.

Captain Becton barked, “Hard left rudder!” The DD, at flank speed, came round hard.

Gunners splashed the Vals coming in to starboard. A third Val, wave-hopping, was hit by 20 mm fire. Its fixed landing gear caught a wave, then pitched into the sea. The fourth Val, off the port quarter, was hit and splashed by gunners from Laffey and LCS-51.

Four up, four down. But the action continued. A pair of speedier Yokosuka D4 Judy dive-bombers came in, one to port, the other to starboard. Gunners blasted the threat to starboard. The second Judy roared in from the port quarter, strafing, was hit by 40 mm and 20 mm fire, then crashed into the sea. The bomb it was carrying detonated, spraying the port side with fragments, wounding several gunners and, knocked out the SG surface search/low-altitude aircraft and fire control radar antenna, as well as a radio antenna.[20]

Then in came another Val from the port beam. Every 5-inch gun opened up, with lesser calibers joining in the symphony of gunfire. The onrushing pilot brushed the 5-inch turret aft, killing one of the gun crew, then plunged into the sea. Then came another Judy to starboard. 40 mm and 20 mm set the gas tank alight, turning the Yokosuka into a torch, then it crashed into the sea.

A ninth attacker, another Judy, from the port beam. 40 mm and 20 mm gunners hit the plane repeatedly, to no avail as the intruder struck the Laffey, taking out a whaleboat before piling into a pair of 20 mm gun mounts and starting a roaring fire abaft the second stack. Two 40 mm mounts atop the deck house were now besieged by flames. Ready rounds began to explode. Sailors rushed to toss unexploded rounds overboard. This attack severed communications with the forward engine room.

The ship that would not die, USS Laffey, DD-724, circa 1945, probably before the savage Kamikaze attack on April 16, 1945 off Okinawa.

Two minutes later, another Val, skimming the sea from astern, raking the deck with machine gun fire, slammed into the DD and exploded. A river of flaming gasoline spread across the fantail. A second Val dropped its bomb, which hit abaft the after 5-inch gun turret, to which the plane struck the turret, killing six men inside.

Then another plane dropped a bomb which struck Laffey astern, severing the hydraulic lines to the steering gear, jamming her rudder to port, leaving DD-724 circling.

The tortured can by now had lost two 40 mm and five 20 mm mounts; a vulnerability compounded by the fires being fought by her crew. And, there was still the air threat.

Two more attackers made a beeline for the stricken can. Every gun that could opened up. From the port quarter, the first plane, a Val, crashed into the after deckhouse, spilling gasoline and starting another fire; followed by a Judy which crashed into the same spot, killing four men. The after deckhouse was now an inferno.

Then a fighter plane, an Oscar, came screaming in, aiming at the forecastle. On its tail, pilot braving the ship’s A.A., was a Corsair, its guns chattering. The intruder narrowly cleared the bridge, taking out the portside yardarm as he crashed into the sea. The pursing Corsair collided with the air-search radar antenna, damaging the plane. The pilot was able to gain altitude, then bailed out. He was later picked up by LCS-51.[21]

Tom McCarthy, a signalman, seeing that the Oscar had taken out the yardarm, grabbed another battle ensign. He affixed same to the mast.

A more detailed combat air patrol arrived. Corsairs from Intrepid (CV-11) and Hellcats from the light carrier San Jacinto (CVL-30). But the battle was over.

Laffey’s situation was extremely critical. Flooded compartments aft left her low astern in the water. Fires aft still raged and, her steering gear was jammed. Air search and surface search radars were destroyed. And with much of the electrical power having been knocked out, many of her guns were on manual. Surprisingly though she was still afloat after taking six Kamikazes and four bombs. Then again, maybe not so surprisingly. For there was her valiant crew, who had leaped to their ship’s defense.

Laffey was accorded a Presidential Unit Citation. Commander Frederick Julian Becton, a Navy Cross. Lieutenant Howell D. Chickering, c.o. of LCS-51, a Navy Cross. Ensign Robert Clarence Thomsen, a posthumous Navy Cross. Other crewmen on the Laffey: six Silver Stars, 18 Bronze Stars and a Navy Letter of Commendation.

And the Laffey? She would be repaired and returned to the fleet. She would later serve during the Korean War and, be accorded two more Battle Stars.

DD-724, the damaged USS Laffey, after the Kamikaze attack on April 16, 1945.

* * * * *

Postscript

In Volume XIV of his epic rendition of the naval war in World War II, Samuel Eliot Morison offered a pertinent analysis of the events at Okinawa: