Looking Back

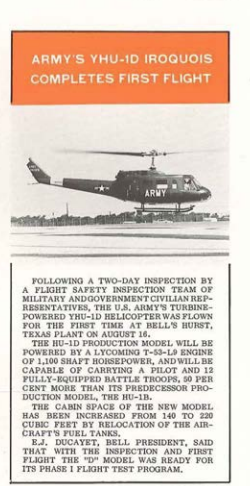

By Mark Albertson

“The Army Air Corps is Back,”[1]

* * * * *

Few taxpayers are aware of the needless expense caused by the duplication of Air Force functions through the formation of another air force by the United States Army. In fact, this Army air force comprises a fourth air force. Complementing those now existing of the Navy, the Marines, and the United States Air Force itself. The wastefulness of this action is shown in the plans of each commander of a field army to use 939 Army aircraft. These are in addition to the Air Force aircraft available to him from normal theater support. The latter alone could adequately supply all his needs. The assignment to individual commanders of airplanes is a throwback to the penny packet method of distributing aircraft learned to be so fallacious in the early North African campaign of World War II. This requirement of almost a thousand Army airplanes in each field army, (of which three are now eight) to perform functions which the Air Force can do most economically, without increased cost to the taxpayer in additional planes, merits careful consideration. It is a subject which should receive close scrutiny by the public, the Bureau of the Budget, and Congress.

The natural desire of an Army commander to control his own aviation, while commendable from the individual commander’s limited viewpoint, must be evaluated in the light of what will give the greatest good to the nation. It has been reiterated many times in recent months that the most pressing problem facing the nation is the maintenance of adequate defense forces for security within our national economy. This cannot be done if the Army continues to obtain and to use airplanes based on concepts of operation learned in World War II and Korea. In truth, some Army concepts of operation even harken back to the Civil War when the mule-drawn vehicle was the best transportation known. The Army is unfortunately downgrading the use of airpower in these obsolete fashions, for it treats the plane as a faster kind of truck or horse to be used over the same route and distances established by trucking methods. Similarly concept of tactical operations still confine its activities to a combat zone geographically defined based on former ground limitations. However, one lesson now being relearned through hard experience by other users of airpower is now being relearned by the Army. That is, the requirement for centralized control of the airpower that it does possess to obtain maximum usefulness. Attempts are being made to do this in the Army Transportation Corps over the objections of other branches and corps of the Army desirous of capturing individual control. This fourth air force, in addition to airplanes, is wastefully duplicating pilot and mechanic training schools as well as supply and maintenance facilities. In fact, with plans for completed world-wide air mobility of the Army, the Army is building up an air force with which it hopes to become entirely independent of any support of the present Air Force.

One example of the wasteful use of aircraft planned is the assignment, within the 939 planes of the field army, of sixty helicopters to be used for the sole purpose of medical supply and evacuation, in addition to this, 467 helicopters may be secondarily used for this purpose. Actually an Air Force troop carrier assault squadron of sixteen helicopters could evacuate from 1,000 to 5,000 casualties per day, which should be adequate for the most pessimistic of commanders. For if this commander intended to use as many as 527 helicopters for casualties, his war would soon be over in favor of the enemy.

An OH-13, from the 25th Infantry Division, evacuating casualties during the Korean War.

However, this wasteful duplication is not the most serious problem presented by the fourth air force. The real problem which will exist with the large number of Army planes programmed for a combat area, will be that of tactical control. A single centralized tactical control system must be set up to identify all planes, locate targets for friendly aircraft, and permit flexibility of assignment of aircraft in a theater of operations. This centralized combat system is now possessed by the Air Force. A duplicating system set up by the Army Air Corps or none at all, to control Army planes would soon make the air over the battle area a snarled-up mess and lead to disaster. Proper air cover must be given throughout a controlled system, for any reconnaissance, supply troop carrier or evacuation missions. One single agency must control all types of air operations in combat, whether fought on the patterns of pre-atomic days or the new concept of flexible mobility and dispersion.

It is to be noted that the Army appears justified in its demands for more air transportation and air support, when considered with the requirements presented unilaterally by the Army. However, when an analysis is made of the actual airlift needed to fight a new type of war with a hard-hitting compact army devoid of many weighty, obsolete, logistical organizations, it is seen that the requirements are preposterous. They are based on the airlift needed to move World War II type armies from mudhole to mudhole.

In the past, budgetary limitations have necessitated the expenditure of most Air Force funds, and justifiably so: To build up the Strategic Air Command as a ready striking force to prevent war. Now, with the need to develop armies that are truly air mobile, it is logical that the Air Force should be the proper custodian of the job in order to do it best and most economically. We should not be influenced by the precedent set in the recent past, of the Army attempting to enter the air business due to default of the Air Force because of its limited budgets. Millions can be saved by taking from the Army all aircraft other than a few small planes needed by commanders for liaison, and even this latter allocation is probably not necessary. It is not unlikely that billions could be saved if the Army coordinated its tactics with proper use of airpower and cut out obsolete methods of operation based on surface-bound views. The claim that scientific advances have now made one airplane capable of doing the work that thousands did in World War II also can be applied to the functions of the infantry. As an example, one ground soldier controlling a number of rocket field pieces can do the work of an entire field artillery regiment.

The resolution of this problem will require a little knocking of heads together by the Commander-in-Chief and the Secretary of Defense. It will require telling the Army to stick to its own business. It will require that the Army cooperate and not compete with the Air Force in developing techniques of using air and ground power to the best advantage of the Nation. It will require that this fourth air force concept be abandoned by the Army.

There is a best way to do a job. The nation’s economy demands that it have that best method through proper unification of the services and the prevention of duplication or quadruplication. National survival and not service survival is at stake.

Colonel Moneysaver

* * * * *

Rebuttal

Colonel Moneysaver’s concluding line is a summation more in tune with that of a political culture as opposed to that of a military dogma: “National survival and not service survival is at stake.” For starters, neither the Air Force nor the Army was in danger of closing its doors in 1955. Rather, it is the control of tactical aviation that is the bone of contention. Indeed, during the late 1940s, even naval air and Marine Corps air will feel that Air Force confidence in controlling airpower. But, of course, the butt of the argument is Army Aviation, as it had graduated, by 1955, from what it once actually was, the Air Observation Post. The Korean War was proof positive where the Army was taking the development of tactical air and, doing so with the helicopter. And, as the writer’s name indicates, the issue of money, taxpayer dollars, is another focus. Control the money, control the agenda. After all, this is a Capitalist country. So follow the money.

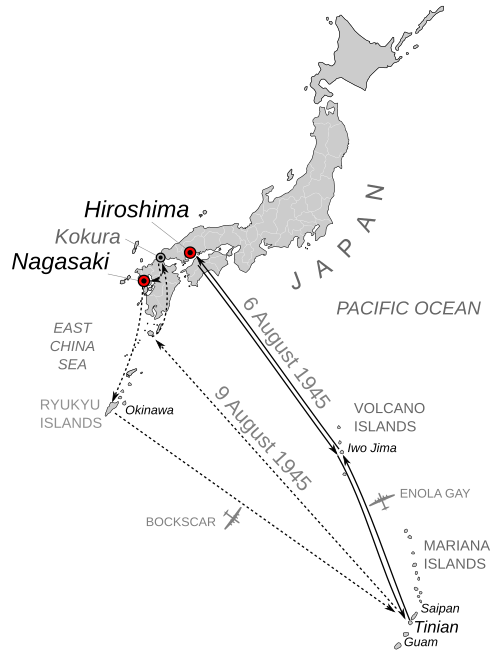

The argument posed by Colonel Moneysaver was decades in the making. Go back to the first chapter of the Great War,[2] on the Western Front, the stalemate of the trenches, where the armies of the Triple Alliance and Triple Entente were mired in that gridlock of shot and shell and mud and No Man’s Land. Far thinkers such as Sir Hugh “Boom” Trenchard, Giulio Douhet and our own Billy Mitchell thought the airplane could break the stalemate. That with the proper bombers an air fleet could take war to the enemy’s capability to wage industrialized war. And do so by targeting such necessities as the factories, port and dock facilities, railroad tracks and rolling stock, communications infrastructure, fuel supplies, ammo dumps, and other targets of consequence to an industrialized war effort. Douhet even added the bombing of the enemy population, since the people might put pressure on their government to conclude the conflict quickly.

History will bear out that Douhet’s notion of bombing the civilians will not always prove an advantage. 1940, the German “blitz” against the British; 1942-1945, Allied bombing of Germany; the later U.S. bombing of North Vietnam, if anything raised the people’s ire to resist.

But to strategic airmen in the United States, the bomber was that medium for an independent service, that ticket for that divorce from the Army. For the bomber represented offensive airpower, in lieu of the fighter which represented defensive air power. And during the 1920s and 1930s this ideal became more and more prevalent.

The Ground Forces of the Army were very much concerned that the tactical requirements of the rifle totter would not be addressed; a concern that was justified. For many of the observation aircraft being designed were large, speedier and hardly conducive for proper ground forces observation and reconnaissance. Yet, too, military aviation was becoming too sophisticated to be controlled by ground officers; or, so it seemed. . .

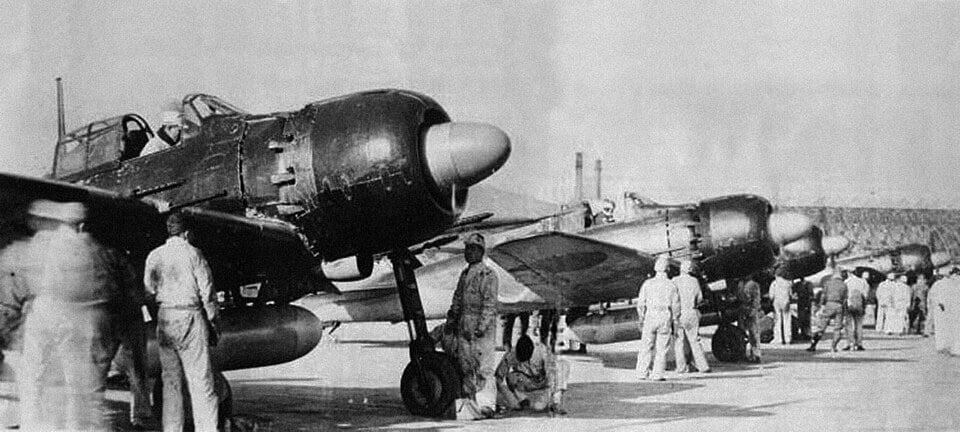

During the second chapter of the Great War, the United States Army Air Forces will never field an aircraft that was devoted solely to ground support and tank busting. Nothing that was American-built of was of a similar effort to the superlative Illyushin IL-II Shturmovik. Indeed, Eddie Rickenbacker, “was shown a demonstration of the Shturmovik’s capabilities and recorded the view that it was the best aircraft of its type in the world; that his country had never produced anything in the same class of machine. . . “[3] The Shturmovik will go on to become the most produced combat aircraft in history at 36,183 copies.

The American equivalent was the P-47 Thunderbolt. The “Jug” was one of the best fighter planes produced by the United States during the second chapter of the Great War. Yet as a ground support tank-busting aircraft, it was a distant second to the Shturmovik. Quite frankly, the United States Army Air Forces did not design an aircraft of the Shturmovik’s quality because it was focused on strategic aviation, which was the strategic airmen’s concern. Arguably then, the best “ground support” aircraft produced by the United States was the L-4 Piper Cub. Manned by Field Artillery personnel, pilots and observers, these flivver planes could focus battalions of artillery onto a single target so as to obliterate same.[4] These aircraft, too, were organic to the units assigned to. And were on the beck and call of the units assigned to. Meaning, they were controlled by the Ground Forces, not the United States Army Air Forces, something of an anathema to the U.S.A.A.F. and, which helped to plant the seeds for that continuing difference of opinion as to who will control ground forces tactical aviation after 1945.

The Piper L-4 Cub was the aircraft that put the Air Observation Post on the map. But by the Korean War it was obsolete.

The L-4 Cub was that aircraft that proved the signature expression of the Air Observation Post, later to evolve into Army Aviation. But following 1945, growing obsolescence will see to the Cub’s replacement, owing to the changing nature of ground forces requirements.

Demobilization followed the cessation of military operations with the conclusion of the global conflict. Starting after September 2, 1945 and out to March 31, 1947, the U.S. Army downsized from 89 divisions to 10, with many of these understrength. The Navy shrank from 1,000 ships to some 300, a seventy percent drop. The U.S. Army Air Forces declined from a high of 213 combat groups to 63; and of these, only 11 were up to full strength.[5]

A corresponding drop in military spending fortified the “peace dividend” leading up to the Korean War. Starting with 1946 from $42 billion down to $14 billion in 1947 to $10 billion in 1949. As a percentage of G.N.P., from 20.7 percent in FY 1946 to 4.4 percent in FY 1947.[6]

* * * * *

July 26, 1947, the National Security Act. With this significant development the U.S.A.A.F will be divorced from the Army to become the United States Air Force. Marine Corps air will remain under the umbrella of the Navy. The War Department was done away with. Instead, three new departments were formed: Department of the Air Force, Department of the Army, Department of the Navy. With the latter, the Marine Corps will retain their air capability and will utilize said capability so as to fulfill those requirements assigned to them as part of the Department of the Navy.

Then the newly-minted Air Force: “In general the United States Air Force shall include aviation forces both combat and service not otherwise assigned. It shall be organized, trained, and equipped primarily for prompt and sustained offensive and defensive air operations. The Air Force shall be responsible for the preparation of the air forces necessary for the effective prosecution of war except as otherwise assigned and, in accordance with integrated joint mobilization plans, for the expansion of the peacetime components of the Air Force to meet the needs of war.”[7]

Now within the second stanza of Colonel Moneymaker’s “The Army Air Corps is Back,” he levels criticism as to the Army commander’s control of his own aviation, or aviation organic to said command, as detrimental to the Nation, based on the concepts of World War II and Korea. Adding here, too, of the duplication of pilots and training schools.

Armies glean and review the mistakes and successes of the previous war so as not to repeat the sins of same in fighting the next. This is precisely what Major General James M. Gavin was attempting when he wrote, “The future of our armed forces is in the air. All the fighting men and everything they need to fight with in the future and live on as they fight must be capable of movement by air.”[8]

General Gavin understood the limitations of parachutes and plywood gliders for the purpose of inserting troops behind enemy lines. For his concept will necessitate new aircraft, new tactics, new training methods. Thinking along the same lines was Lieutenant General Roy S. Geiger, Commander, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific Fleet. In 1946, he attended the Navy’s atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll, where 247 ships were moored in the Bikini lagoon. Upon his return to his office at Pearl Harbor, he wrote a letter to Marine Corps Commandant, General Alexander “Archie” Vandergrift. To the effect that amphibious landings as seen at Sicily, Normandy and Okinawa were becoming a thing of the past. Warning of the devastation of a single atomic bomb dropped on a beach crowded with troops, he suggested the use of light aircraft to disperse assault forces in and around the beaches and then at the proper time the use of such aerial assets to effect the consolidation of such forces to commence operations.

General Vandergrift supported Geiger’s thinking out-of-the box which will result in the Vertical Assault Concept. To which concern as to the effects of the atomic bomb will help lead to the post-1945 development of the helicopter. With the Marine Corps, the Vertical Assault Concept will see to the conversion of World War II escort carriers into amphibious assault ships able to carry helicopters and marines. It would seem that here, both Gavin and Geiger understand that the helicopter unlike parachutes are much more accurate in landing airborne assault troops in assigned areas of operations and are consistently more reusable than plywood gliders. Unlike the French in 1940 who fought the Wehrmacht as it did the Kaiser’s army in 1914, both Gavin and Geiger were not seeking to fight the next war as it was done in 1939-1945.

Stanza three, Colonel Moneymaker’s criticism of Army aircraft being used for “medical supply and evacuation.” Author’s argument was that “an air force troop carrier assault squadron of sixteen helicopters could evacuate from 1,000 to 5,000 casualties per day . . . for the most pessimistic of commanders. For if this commander intended to use 527 helicopters for casualties, his war would soon be over in favor of the enemy.”

Let us understand the reality here. Colonel Moneymaker is elaborating on a long-sought agenda by airmen for airmen for independence from the Army. This is in the face of now the Army’s expression of pseudo-independence from the Air Force. And same is based on why? Recent history.

March 1946, Tactical Air Command was formed, based on a promise Army Air Forces Commander, General Carl A. Spaatz, made to Army Chief of Staff, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Yet nine years later, 1955, the Air Force had no intention of fielding an aircraft solely for the purpose of close air support; rather, aircraft to establish air superiority and, once established, support of the ground forces will rely on jets of high speed, to which, too, are multi-role aircraft in keeping with Air Force independence. Indeed, T.A.C. aircraft were being modeled for low-level nuclear ordnance. Hardly the C.A.S. requirements of the ground forces. In fact, during the early stages of the Korean War, the Army Chief of Staff called for the subordination of Air Force aircraft conducting air support to army corps and division commanders, including Air Force fighter-bomber squadrons being attached to each Army division.

“In Korea itself, in 1950, the Army got to experience the apparent benefits of Marine tactical air doctrine at first hand when Marine aircraft provided dedicated support to Army units during the defense of the Pusan perimeter and Inchon landings, and Army officers liked what they saw. Drawing on this experience, General Edward M. Almond, commanding the Army’s X Corps, recommended in December 1950 and again in July of the following year, that a group of fighter-bombers be allotted to the operational control of each Army division.”[9]

Yet following Korea, President Eisenhower did not want America in such a conflict, believing that the constant repetition of war would turn the United States into a garrison state. So between 1953 and 1957, the Army was cut from 20 divisions to 14. Ships were mothballed from the Navy and there were reductions in personnel. But the Air Force increased by 30,000 men and more air wings as its budget increased. For this was the era of the New Look Defense with a cornerstone of “Massive Retaliation” with the strategic bomber delivering atomic ordnance. The threat of bombing an opponent back into the “Stone Age,” was deterrence.

Yet the Army will plan and train to fight on a nuclear battlefield. It will reorganize the division structure to conform to a developing reality in the late fifties, the Pentomic Division. And the Army will bet the ranch on the helicopter, an aircraft that will be under constant development for the ground forces. And this will include Colonel Jay D. Vanderpool, who was not an aviator, experimenting with arming the helicopter, paving the way for not only the troop carrying helicopter, but future rotary wing aircraft able to provide close support for the soldier on the ground and flown by Army aviators.

Colonel Moneymaker’s article was a continuation of Lieutenant General Henry “Hap” Arnold’s earlier warning of the Army developing a rival air force. Yet there was the prophetic observation later by Pete Quesada who stated, that if the Air Force did not service the Army’s tactical requirements, that a rival air force will arise. He was, of course, proven correct.

Stanza Four: Note here, Colonel Moneysaver states that the Army “appears justified in its demands for more air transportation and air support, when considered with the requirements presented unilaterally by the Army. However, when an analysis is made of the actual airlift needed to fight a new type of war with a hard-hitting compact army devoid of many weighty, obsolete, logistical organizations, it is seen that the requirements are preposterous. They are based on the airlift needed to move World War II type armies from mudhole to mudhole.”

Rebuttal: What is preposterous here is the concerted lack of regard for history. To start with, strategic bombing, as it would come to evolve, would not have been possible without the horrific and grievously costly gridlock of the trenches in eastern France north through Belgium on the Western Front, 1914-1918. Far ranging thinkers such as Trenchard, Douhet and Mitchell saw strategic aviation as that option of taking war to the enemy’s industrial capability of waging war; to which, strategic aviation will be another facet of Levee en Masse, with the growing sophistication of waging modern industrialized, corporatized, commercialized war, Total War.

But then, within this whirlpool of Total War, one cannot just give the tactical requirements the short shrift; which lends to the question, just where does Army Aviation fit in?

Well let us begin with the demonstrated ability of the Air OPs to perform a variety of tasks other than that of the aerial direction of artillery fire, which not only enhanced its value but broadened its appeal. This became evident when other branches of the Ground Forces utilized Field Artillery Cubs for tasks and missions other than that originally intended.

In August 1945, the War Department gave the Air Observation Post a boost by enabling other branches of the Ground Forces—Armor, Engineers, Infantry, Cavalry, Tank Destroyers—to adopt the capability.[10] The agreement, which had been reached privately by Jacob L. Devers, C.G. Army Ground Forces and General Ira C, Eaker, C.G. Army Air Forces, also called for additional light aircraft for the A.G.F.[11]

Yet following the divorce of the Army and the Air Force, the latter was still procuring aircraft for the former. And despite the Army truly beginning to focus on the helicopter, the Air Force considered tactical aircraft a distant second on the priority list to that of strategic aviation.

For instance, “in 1948, Lieutenant General James M. Gavin, in his capacity as president of the Army Airborne Panel, attempted to convince the Air Force director of requirements of the Army’s need for more and larger helicopters. Finally exasperated by LTG Gavin’s persistence, the Air Force general replied,–

“I am the director of requirements and I will determine what is needed and what is not. The helicopter is aerodynamically unsound. It is like lifting oneself by one’s bootstraps. It is no good as an air vehicle and I am not going to procure any. No matter what the Army says. I know it does not need any.”[12]

In just two years, those words will be meaningless. Actually, they were without foundation when uttered. For with the opening of the Korean War, the Air Force committed two rescue squadrons, the 2nd and the 3rd. The 2nd served the needs of the 13th and 20th Air Forces and was based out of Clark Field in the Philippines; while the latter served the Fifth Air Force and covered the area in and around Japan. Among their aircraft, the Sikorsky H-5 (S-51) helicopter.

A Sikorsky S-51, HO3S-1 in service in Korea as a medivac. Note litters on the rungs.

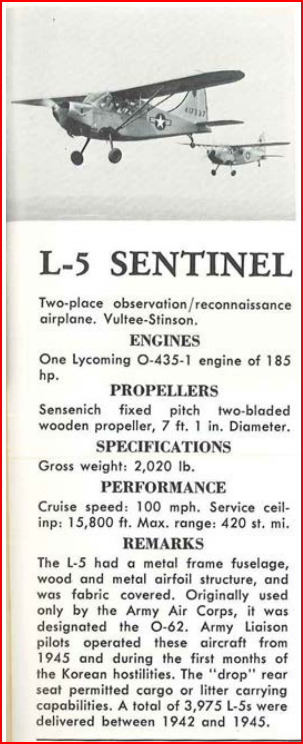

July 7, 1950, a pair of Stinson L-5s were sent to Korea as rescue aircraft; to which among the tasks was to recover downed airmen behind enemy lines. These proved unequal to the task. For instance, the L-5, unlike the L-4 Piper Cub, was not as suitable a choice for soft ground landings such as on cow pastures and paddy areas. This, of course, was rectified with the use of helicopters. H-5s were put to work for rescue operations, flying out of Taegu[13] in the Pusan perimeter.

Another holdover from World War II. Used in a variety of liaison tasks in Korea, including medical evacuation. But it was quickly replaced as a medivac by the helicopter.

“By the end of August, meanwhile, the 3rd Rescue Squadron’s helicopters had flown 83 critically wounded soldiers from the battle area. All of them would almost would certainly have died had they been forced to make the journey to a field hospital by ambulance.”[14]

“By the end of 1950, the H-5s had transported 618 medical cases, compared to the 56 flown out by L-5s.”[15] Indeed, an aircraft viewed as “aerodynamically unsound,” by the Air Force director of requirements for the Army was being proved as “in error.” Though one must consider the alternative here, that the Air Force or, at least said officer, had little regard for the tactical requirements of the Army.

The Marine Corps, too was making use of the helicopter for moving men and stores and retrieving downed airmen, besides shuttling wounded to doctor’s care.

The Army did not get into action until December 1950. Bell H-13s, to be complemented in short order by Hiller H-23 Ravens, were to be used for artillery fire direction, chores of liaison and evacuation of battle casualties. By January 1951, Captain Albert Seburn was in command of the 2nd Helicopter Detachment based at Seoul. And in just a month, some 500 casualties had been evacuated.

For the Army, the eclipse was now becoming complete: The Air Observation Post was now becoming Army Aviation.

Stanzas 5 and 6: In opposition to Colonel Moneysaver, the lack of regard for history is quite evident here . . . that being, of course, the repetition of history. For history does repeat, though it is never exact, but does repeat. Or as put forth by Mark Twain, as opposed to repeating, history rhymes.

With the Sikosky H-19, the Army was now able to haul men and stores for the tactical requirements of the ground forces.

1914-1945, the evolving nature of strategic aviation, the desire of the proponents of same to seek a separate service, is based, in part, on the growing sophistication of military aviation in the era of Levee en Masse. Strategic aviation is becoming too sophisticated to be overseen by ground officers. But with the atomic age and the evolving transition of the Industrial Revolution to that of the Technology Revolution, there was and still is the evolving transition of the sophistication of ground warfare; to the extent that it should be the province of ground officers. For in the end, they will be the best qualified for understanding the rudiments of close support tactical air because they have to wage it. Marine Corps air supports the man with the rifle. So, too, Army Aviation, which provides one with a better understanding of why it is no longer the Air Observation Post. But please note, . . .

. . . thinkers of their time, such as Trenchard, Douhet, Mitchell, later William Wallace Ford, Delbert Bristol, Robert Williams, James Gavin, Roy Geiger and others like them, were revolutionaries, minorities within accepted convention but, who will alter and change the status quo. It is those who follow who cement these revolutionary ideals into the new convention and therefore, give way to a new generation of reactionary proponents who will be difficult to unseat. For as General George Seneff observed, Yesterday’s revolutionaries are tomorrow’s reactionaries.” Such is the article being critiqued, an effort into maintaining the new status quo and penned by Colonel Moneysaver, versus the perceived threat posed in 1955 by those upstarts in Army Aviation.

Endnotes

[1] See page 46, Army Aviation, February 28, 2001 issue. Reprinted with permission of Air Force Magazine, September 1955.

[2] Those familiar with past Looking Back efforts know that this writer does not conform to the accepted historical progression of World War I, 1914-1918 and World War II, 1939-1945. There is only one war, Man’s greatest industrialized, corporatized, commercialized conflict, the Great War, 1914-1922; 1931-1945. Levee en Masse, the conscription of entire economies and populations for industrialized Total War was in full bloom. The result will be the demise of European domination of the globe and a new balance of power, that of the United States and the Soviet Union. The resulting faceoff will be known as, the Cold War.

[3] See pages 12 and 13, Aircraft Profile, No. 88, The Ilyushin-2, March 1982, by Witold Liss.

[4] The venerable L-4 Piper Cub was one of the most cost effective military aircraft in American history. It was rugged, easy to maintain, able to operate from hard airfields at the rear or soft fields near the front, and, it was a bargain at some $2,000 per unit. A crew of two, pilot and observer from the Field Artillery, could zero in battalions of gun batteries onto a single target in a devastating display of firepower, as acknowledged by Germans who were on the receiving end of such firepower. A distinct improvement from World War I where hundreds or even thousands of guns shelled opposing forces minus such an advance in targeting methods.

[5] See page 2, Army Aviation: The Interwar Years, 1945-1950, A History of Army Aviation Logistics, 1936-1961, Study No. 5, by Dr. Howard K. Butler.

[6] See pages 1 and 2, Dr. Howard K. Butler.

[7] See pages 44 and 45, “The National Security Act of 1947,” The Department of Defense, 1944-1978, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Historical Office.

]8] See page 178, The Field Artillery Journal, May-June 1947, by Major General James M. Gavin, U.S.A.

[9] See page 16, Chapter 1, “The Doctrinal Background,” Inter-service Rivalry and Airpower in the Vietnam War, by Dr. Ian Horwood.

[10] See page 3, Chapter 1, “The Field Artillery in World War II,” History of the Field Artillery School, Vol. II, by the Field Artillery School.

[11] See page 15, “Academics and Training,” Part II, The Army Aviation Story, by Richard K. Tierney.

[12] See page 25, “Army Aviation Between WWII and the Korean Conflict,” by Dr. John Kitchens, Aviation Branch Command Historian, U.S. Army Center, Fort Rucker, Alabama, U.S. Army Aviation Digest, September-October 1992.

[13] Today known as Daegu.

[14] See page 108, Chapter Ten, “Battlefield Support, 1951,” Air War Over Korea, by Robert Jackson.

[15] See page 109, Robert Jackson.

Bibliography

ADA951856, History of the Field Artillery School, Vol. II, “World War II, U.S. Army Field Artillery School, Fort Sill, Oklahoma, October 31, 1946.

Butler, Dr. Howard K., “Army Aviation: The Interwar Years, 1945-1950,” History Study No. 5, A History of Army Aviation Logistics, 1935-1961, Historical Division, U.S. Army Aviation Systems Command, St. Louis, Missouri, 1988.

Fort Rucker and Army Aviation History, “20th Anniversary of Army Aviation: The Army Aviation Story,” Part II: “Academics and Training, 1942 to the 1950s,” by Richard K. Tierney, United States Army Aviation Digest, U. S. Army Training Center, Fort Rucker, Alabama, July 1962.

Gavin, Major General, James M. U.S.A., “Airborne Armies of the Future,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 37, No. 3, U.S. Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., May-June 1947.

Gavin, Lieutenant General James M., War and Peace in the Space Age, Harper & Brothers Publishers, Inc., New York, NY., 1958.

Horwood, Dr. Ian, Inter-service Rivalry and Airpower in the Vietnam War, Army Combined Arms Center, Combat Studies Institute, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 2006.

Jackson, Robert, Air War Over Korea, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1973.

Kitchens, Dr. John W., Aviation Branch Historian, “Army Aviation Between WWII and the Korean War,” United States Army Aviation Digest, Professional Bulletin 1-92-5, U.S. Army Aviation Center, Fort Rucker, Alabama, September-October, 1992.

Liss, Witold, The Ilyushin Il-2, Profile Aircraft, No. 88, Profile Books Limited, Berkshire, England. Printed in Canada by the Bryant Press Limited, Toronto, Ontario, March 1982.

Moneysaver, Colonel, “The Army Air Corps is Back,” Army Aviation, Vol. 50, No. 2, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., February 28, 2001

Munson, Kenneth, Aircraft of World War II, Ian Allen, 1962. Published by Doubleday & Company, Inc., and printed in Great Britain by Crampton & Sons, Ltd., Sawston, Cambridge, 1968.

The Department of Defense, Documents on Establishment and Organization, 1944-1978, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Historical Office, Washington, D.C., 1978.

Tierney, Richard with Montgomery, Fred, The Army Aviation Story, Colonial Press, Northport, Alabama, 1963.

Looking Back, November 2025

By Mark Albertson

Operation: DESERT SHIELD

* * * * *

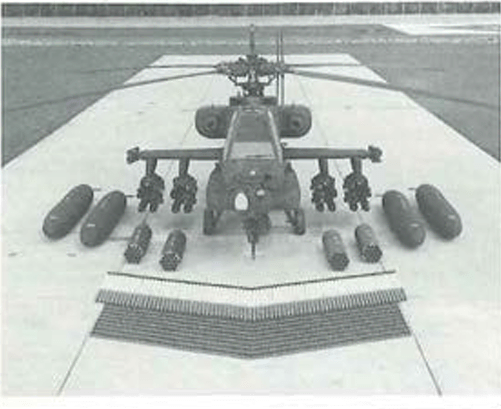

The single biggest maneuver factor on the battlefield was the Apache. If there was one leverage device that we used it was the Army general support aviation battalion. In my judgment, for the number of soldiers involved, and the price involved, the biggest leverage we got out of the very few numbers of helicopters, the tiny number of helicopters, that we devoted to support logistics, and command and control in general: the Signal battalion commander, the Maneuver Brigade commanders, the DISCOM commander, and the Division G3. Had COL James King (DISCOM Commander) not had Army Aviation UH-60s, UH-1s and Chinooks, there would have been a far different outcome. Many of us will never know the full story on that one. It made the difference of getting POL to the right spot because we could move the key logistics around the battlefield.

Who won the battle? Certainly, the artillery and the Apache. It will be hard to remember that eleven years from now, when you are in charge of force development working 20 hours a day. The artillery and the Apache are the hammers that make the endgame work.[1]

* * * * *

Economics of War

Colonel Tackaberry’s observation on the success of airmobility over Saddam’s host during Operation: DESERT STORM must conform to the preparatory process. For victory is not possible without same. And to understand that victory, we must return to that series of events that led up to STORM.

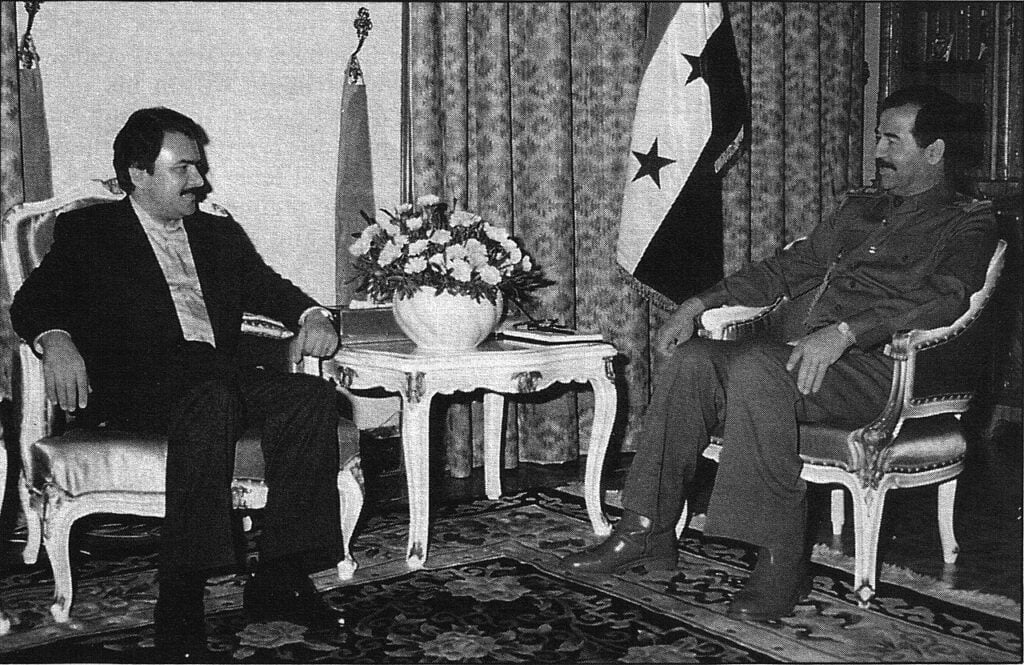

Saddam marched into Kuwait, August 1990, and triggered the massive military response to evict him from Kuwait, known as Operations: DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM. Shown with Saddam in this 1987 photo is Massoud Rajavi, leader of the Iranian People’s Mujahidin.

August 1, 1990, Saddam Hussein sent his army crashing into Kuwait. One week later, he had annexed same.[2] Yet Efraim Karsh provides the rationale for Saddam’s actions:

“Though the Iraqi regime went out of its way to portray the end of the war as a shining victory (that is, the Iran-Iraq War), the truth was that Iraq, no less than Iran, emerged from the eight-year conflict a crippled nation. At least 200,000 Iraqis had lost their lives, while about 400,000 had been wounded and some 70,000 taken prisoner; an exorbitant price for a nation of 17 million people. In 1980 Iraq could boast of a $35 billion foreign currency reserve; eight years later it had accumulated a foreign debt of some $80 billion—roughly twice the size of its Gross National Product. This debt was extremely onerous, since repayment arrears and the consequent reluctance of foreign companies and governments to extend further credits meant that the reconstruction of Iraq from the destruction wrought by the war would have to be shelved.

“Economic estimates put the cost of reconstruction at $230 billion. . . As things were a year after the termination of hostilities, Iraq’s oil revenues of $13 billion did not suffice even to cover ongoing expenditures: With civilian imports approximating to $12 billion ($3 billion for foodstuffs), military imports exceeding $5 billion, debt payments totaling some $5 billion; and, transfers by foreign workers topping $1 billion, the regime needed an extra $10 billion per annum to balance its current deficit, before it could even think of reconstruction; and this without taking into account the substantial domestic economic costs, such as the $2.5-$7.9 billion defense expenditure.”[3]

The harsh economic realities unfolding underscored the political corner Saddam had painted himself into. He needed cash and, in one quick hurry. In February 1990, in Amman, Jordan, Saddam petitioned King Hussein and President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt to notify the Gulf States that Iraq wanted a postponement on the loans by its “principals” during the war with Iran. And in addition, Baghdad wanted another $30 billion to boot.

Bottom line was that Iraq was over its head with $80 billion in red ink. Kuwait chose not to overlook $65 billion in economic assistance to Iraq in its war against its Persian neighbor. Baghdad countered that Iraq’s invasion of Iran was in Kuwait’s and Saudi Arabia’s benefit, since Saddam was carrying the Arab standard against the detested Shia Fundamentalist regime in Tehran. This, in addition to Iraq’s complaints that Kuwait was reaping undeserved oil profits from the Rumaila oil field, located as it was in territory under dispute by both Iraq and Kuwait. Baghdad, too, was hardly happy with the price of oil being depressed owing to the oil glut, blaming Kuwait for overproduction.[4]

“To pay off his country’s debts, Saddam Hussein needed oil prices to remain in the range of $25 a barrel (at the height of the Iran-Iraq War, prices had reached as high as $35 a barrel). He watched in despair as the international price slumped to $14 by July 1990. The Gulf, at peace once again, was now able to export all the oil the world needed. To make matters worse, some Gulf States were producing well beyond their OPEC quotas. Kuwait was one of the worst offenders. Kuwait had its own reasons for breaking ranks with OPEC over production quotas. Earlier in the 1980s, the Kuwaiti government had diversified its economy by investing in Western refineries and opening thousands of gasoline stations across Europe under the new brand name ‘Q-8,’ a homonym for ‘Kuwait.’ Kuwait’s crude oil exports increasingly went to its own facilities in the West. The more crude oil the Kuwaitis sold to their refineries, the higher their profits in Europe. These refining and marketing outlets generated higher profit margins than the export of crude and insulated Kuwait from variations in the price of crude oil. Kuwait was more interested in generating maximum output than seeking the highest price per barrel by hewing to OPEC’s guidelines.”[5]

But what does the above economic explanation have to do with Army Aviation? Simple, war is economics, as stated by none other than Adolf Hitler. Economic primacy is the major factor for the preservation of the modern American military. Paramount, if you will, of the preservation of American interests; which underscores the striving of fashioning an American military able to respond at a moment’s notice. Same has been reinforced on the pages of Army Aviation magazine, the publisher of this work. Yet . . .

“. . . As a strategic force, the Army must be prepared for instantaneous transition from peace to war. Our Army is trained and ready to make that transition should we ever be called upon to do so.”[6]

That “instantaneous transition” as alluded to by General Vuono has already been showcased with the invasion of Grenada. What will transpire in the liberation of Kuwait would provide a window, though, into Army Aviation’s role to be played in the AirLand battle concept. What far-sighted individuals such as Generals William DePuy and Donn Starry were attempting to forge in the wake of the calamitous result of Vietnam, came to fruition during Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

* * * * *

From Staunch to Storm

The preparatory phase of Desert Shield/Storm was the Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988. This conflict was an overt threat to Western energy interests, since more than fifty percent of the globe’s marketable and tradeable crude flowed from the area in contention The basic preference of the West in this conflict can be seen within the analysis of Anthony Cordesman in 1987:

“The West will not benefit from U.S. efforts directly supporting Iraq with weapons or other major assistance. This is a role that France and other European nations can perform. U.S. support of Iraq should be indirect, and linked to efforts to open lines of communication to Iran and to strengthen the southern Gulf States. In practice, this means using every political means to limit arms shipments to Iran, providing quiet intelligence support and providing political support for every serious peace initiative.

“The U.S. will, however, need to revitalize and sustain ‘Operation: STAUNCH,’ the U.S. effort to halt the flow of arms to Iran that began in 1983. It will need to continue to provide Iraq with agricultural credits, and be ready to support emergency aid by the EXIN (Export- Import) Bank and collective action by the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and World Bank. The U.S. should continue to share intelligence with Iraq of a kind it has provided since mid-1984 and to make every effort to reduce the risk of a successful Iranian offensive or surprise attack.

“In contrast, Europe needs to halt its arms shipments to Iran as much as possible and to concentrate on building up economic ties. It needs to be ready to extend and renegotiate loans, and help ensure Iraq can keep fighting. France plays a particularly critical role. Its arms supplies to Iraq are vital not only to preventing an Iranian victory, but to reducing Iraqi dependence on the USSR.”[7]

But the Iran-Iraq War proved a decisive factor in the destabilization of the most strategic area of the globe. Saddam Hussein, seeking to position Iraq as the new major Arab power in lieu of Egypt, which no longer was, expected quick victory in severing the Iranian province Khuzestan, known to Arabs as “Arabistan,” which would most certainly solidify Saddam’s effort at domination of the Arab world, let alone, perhaps, OPEC. For 70 to 80 percent of Iran’s oil reserves are in Khuzestan. Not only would Saddam be able to improve his standing and political advantage among Arab councils, but would cause irreparable damage to the Shia standard bearer, Iran.

Both Iraq and Iran emerged from the resulting protracted conflict crippled. The Iraqis, as mentioned previously, incurred upwards of 200,000 dead and another 400,000 wounded, with an additional 70,000 taken prisoner. Heavy losses for a nation of only 17 million. But a proper understanding of the opponent the Iraqis were engaged with for eight years is called for:

The Shia Fundamentalist regime in Iran had purged some 12,000 officers from the hated Shah’s regime that had been recently toppled. The Khomeini government created its own militia, the Pasdaran or Revolutionary Guard, a political military formation organized to act as a prophylactic to potential counterrevolution. Hence the aforementioned purge.[8]

On March 20, 1982, another military formation was formed in Iran: Basij e-Mustazafin or Mobilization of the Deprived, featured the mobilization of the young, those ages 12-18, organized into what were literally, in many instances, suicide squads.

Many of these recruits came “mainly from rural areas or from the most devout Shi’ite families, these poorly trained and ill-equipped youths, some as young as 12, were little more than cannon fodder or human minesweepers sent in advance of Iran’s other military forces to clear fields, desert scrubland and marshes. With their red and yellow headbands proclaiming Allah’s or Khomeini’s greatness, a piece of white cloth pinned to their uniforms as a symbol of a shroud, each one carrying his death with him, and a plastic key around their necks, issued personally by Khomeini as a symbol of their assured entry into paradise upon martyrdom, they charged towards Iraqi positions in total disregard of the danger to their lives, and to the shocked disbelief of their enemies.

“They came on in their hundreds, often walking straight across the minefields, triggering them with their feet as they are supposed to do. . . “ See page 62, “Iran’s Boy Soldiers,” The Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988, by Efraim Karsh.[9]

Such an opponent was pulling out all the stops to throw out the invader. And, was emblematic of the brutality of this conflict. A conflict which, together with the rise of the Shia fundamentalist regime in Tehran, would help to harden the lines of division between Shias and Sunnis and lend to what will become the faceoff between the Shia standard bearer Iran versus the Wahhabi agenda in Riyadh.

The year following the end of the Iran-Iraq War, the Soviets would evacuate Afghanistan, presaging the decline and collapse of not only the Soviet Union but also its vassal states in Eastern and Central Europe. The bipolar balance of power that had replaced the end of European domination of global affairs as of 1945, had given way to a unipolar world as the United States became the sole superpower. Yet the peace dividend that many expected has proven to be an illusion, one typical of the human condition. For China was coming on as a competitive power; as was India, Japan was still in the game. The European Union was trying to find itself in an uncertain New World Order, as was a struggling Russia.

Yet the Soviet incursion into Afghanistan and the ensuing Carter Administration assistance of the Mujahideen, carried forward by the Reagan Administration, opened a new conflict, that of the Jihadis. If they could throw an infidel power out of Afghanistan, then what could they do in the Middle East, after centuries of tiresome Western meddling and incursions.

* * * * *

Shield to Storm

“At about 2 a.m. (Baghdad time) on August 2, 1990, three Iraqi Republican Guard divisions invaded Kuwait. One proceeded down a coast road to Kuwait City, a second seized the inland oil fields, and the third proceeded to the Saudi Arabian border. Kuwaiti A-4 aircraft and Chieftain tanks fought for three days until their fuel and ammunition were exhausted. The small Kuwaiti Navy also made a valiant showing, with the last two fast attack craft escaping while firing at pursuing Iraqi tanks.

“Iraqi forces quickly captured Kuwait City and the Emir’s palace, while the Kuwaiti ruler, Sheik Taber al-Ahmed al-Sabah, fled to Saudi Arabia and established a government-in-exile. On August 3rd, the remainder of Kuwait was captured and by the 4th, Iraqi forces were massed along the Kuwaiti-Saudi border for a possible invasion of Saudi Arabia. If Iraq occupied Saudi Arabia, it would not only establish itself as the secular leader of the Arab world, but would also control forty-five percent of the world’s oil.”[10]

If Saddam had banked on the Soviet Union acting as a counterweight to the U.S. and NATO taking action to prevent his Anschluss with Kuwait, he most certainly had miscalculated. For the Soviet monolith was well along that progression of collapse; in addition to the unfolding demise of the Warsaw Pact, which demonstrated unequivocally what that “military alliance” really was, an empire.[11] Perhaps, too, the Iraqi dictator had thought that America had not recovered from the Vietnam debacle.

Following Saddam’s steamrollering of Kuwait, the United States and its NATO allies poured military personnel and equipment into Saudi Arabia. But due to the efforts of James Baker, forces other than that of the United States and NATO formed a broad-based coalition.[12]

“President George Bush, Sr., ordered American military forces to Saudi Arabia on August 7, 1990. By August 11, 13 Army helicopters had arrived in country. By the time the ground war began on 24 February 1991, XVIII Airborne Corps had 920 aircraft in Saudi Arabia, VII Corps had deployed 808, and Echelon Above Corps (EAC) and Army Special Forces had 160 for a theater total of 1,888 Army aircraft. During the period of August 1990 through March 1991, 2,010 Army aircraft flew 182,960 hours as part of the Army team. Ten aviation brigades directly participated in combat operations and other aviation forces provided essential combat support and combat services support to the theater.”[13]

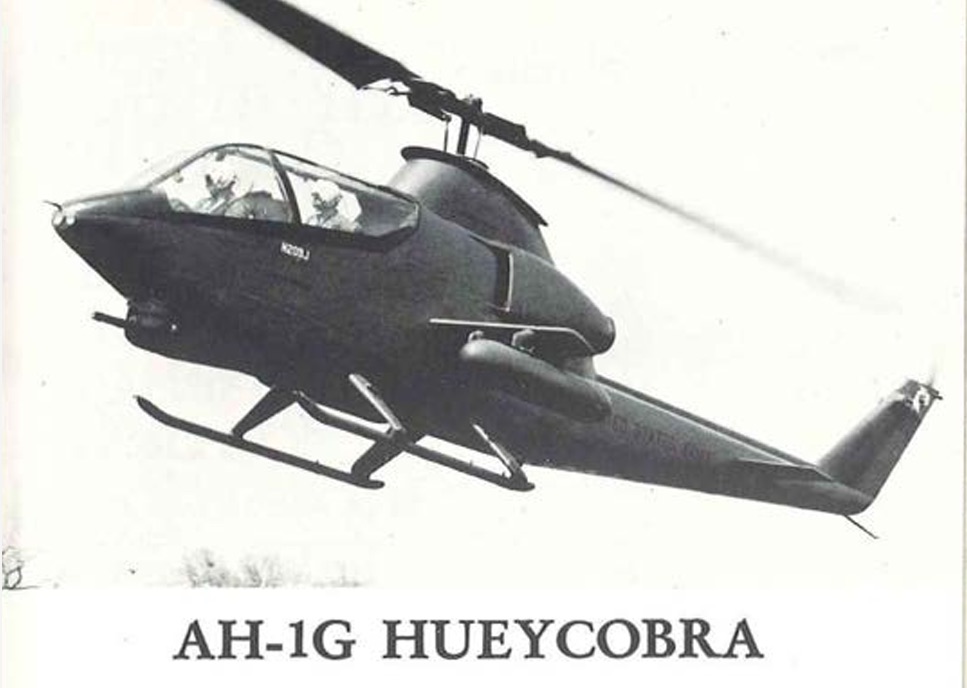

The AH-1G Huey Cobra was Army Aviation’s first true attack helicopter. Coming out of Vietnam, it will be the Army’s attack helicopter until the advent of the AH-64 Apache. The Cobra still performed in the Operation: DESERT STORM.

Yet according to Major General Donald R. Williamson, “Operation Desert Shield found the U.S. Army Aviation Systems Command (AVSCOM) operating on an underfunded spares budget supporting an over-programmed flying hour program.”[14] Production, though, was expanded and accelerated. Additional stocks, transport of supplies, maintenance of aircraft and equipment to accommodate not only a noticeable increase in flying time, but the expected wear and tear with operations in a challenging environment.

“This stepped up activity included over $300 million in new procurement, 2,000 spares programs accelerated, and 600 depot programs surged. This magnified response by both AVSCOM and industry was only hampered by lead times for raw materials and in some instances, forgings and castings.”[15]

The AH-64 Apache became and still is the Army’s premier attack helicopter, having assumed that mantle from the AH-1 Cobra.

In face of the wear and tear in the desert, Colonel Thomas W. Garrett, Commander, Aviation Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, explained some of the conditions faced even in the assembly areas:

“Even at semi improved areas, the sand and dust quickly began to exact a heavy maintenance toll. Blade erosion, engine problems, and avionics trouble were the most worrisome. Our newest aircraft have faired the best. AH-64, OH-58D and newer UH-60s (in order) have held up well. Dust control has become a major concern. Low cost, widely available, and easily applied dust control measures are urgently needed.

UH-60 Black Hawk replaced the aging UH-1 Huey as the utility helicopter for the AirLand Battle Concept.

“Desert night flying has proved to be the toughest of challenges. We are adjusting tactics and techniques to allow us to continue to accomplish our mission, but we had to learn the hard way. Heads up displays for goggles, continued goggle refinement in the areas of acuity and field-of-view, forward looking radar altimeters, and aural altitude warning would greatly enhance our ability to conduct safer night desert operations. A system like the USAF’s ‘Harvest Bare’ needs to be reviewed by Army Aviation. Crew rest, especially for night crews, is next to impossible. A portable base like ‘Harvest Bare’ would be a present from Heaven for many an aviation brigade here in Saudi Arabia.

“Accurate navigation in a featureless desert, day or night, has been challenging. Old maps coupled with shifting dunes and lake beds make even Doppler update waypoints suspect (if you’re lucky enough to have Doppler), allowing for drift errors to build. We must press on with GPS hand-held commercial LORANS, which have been a life saver.”[16]

Perhaps it was Major General Rudolph Ostovich, III, then Chief, Aviation Branch, Commanding General and Commandant, U.S. Army Aviation Logistics School, who observed that with the coming end of the Cold War, the Army was to be reduced, from 28 divisions to 22, resulting, then, in fewer forward deployed forces. “The forces stationed in CONUS will provide both reinforcing combat power for forward deployed forces as well as a contingency capability to respond quickly and decisively in support of our national security interests. Our contingency forces will include heavy, light, and special operations units and there will be a premium on deployable weapons systems that are both versatile and lethal. Army Aviation stands at the forefront of these initiatives. Pound for pound, we are the most deployable, versatile, and lethal of today’s Army forces.”[17]

He continues his analysis, thus: “In response to the challenges in our future, CG, TRADOC initiated Studies and General Officer workshops to redefine our doctrine and identify alternative balance force structures. Through these concept development vehicles, we examined an emerging doctrine tagged AirLand Battle-Future. The concept is founded on a precept that future battlefields will be nonlinear. By this, we mean that no longer will we have the forces to line up hub to hub or rotor to rotor and stretch from coast to coast. We accept the fact that there may be large gaps between formations. We will no longer concentrate our effort to seize and hold terrain.”[18] Rather we will focus our destructive power on the enemy force. We will employ state-of-the art intelligence gathering sensors and air cavalry to find and fix the enemy. Attack helicopters, Close Air Support/Battlefield Air Interdiction, and long-range artillery fires will shape the battlefield for decisive destruction of the enemy through high speed and dynamic maneuver. Depth and rapid concentration of overwhelming destructive power are the essence of aviation’s contribution to our future as a fighting doctrine.”[19]

* * * * *

Endnotes

[1] See pages 28 and 29, “24th Aviation Brigade in Desert Storm,” Part I, Army Aviation, June 30, 1991, by Colonel Burt S. Tackaberry.

[2] See page 152, Chapter 8, “Bush, Clinton, and the Triumph of Wilsonianism,” The Folly of Empire, by John B. Judis.

[3] See page 89, “A Costly Exercise in Futility,” The Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988, by Efraim Karsh.

[4] See page 17, Part 1, “The Prelude,” Military Lessons of the Gulf War, by Bruce W. Watson; Bruce George, Labor MP; Peter Tsouras and B.L. Cyr.

[5] See page 442, Chapter 14, “After the Cold War,” The Arabs, A History, by Eugene Rogan.

[6] See page 4, “Training and Readiness,” Army Aviation, May 1, 1989, by General Carl E. Vuono.

[7] See page 158, Chapter Eight, “The Impact on Western Policy,” The Iran-Iraq War and Western Security, 1984-87, by Anthony H. Cordesman.

[8] In Egypt, beginning in 2011, the uprising against Hosni Mubarak, eventually resulted in the Muslim Brotherhood attaining power, though only briefly. The Egyptian armed forces reclaimed power, unseating the Brotherhood. Understood among the Egyptian Officer Class was the brutal purging of the Shah’s officer class by the Shia fundamentalists in Iran. History, here, In Egypt, was not to be repeated.

[9] Throughout history, nations or empires attempting to deal with manpower shortages, or generate manpower superiority in the face of material disadvantages or seek to galvanize patriotism or, seek to create a more disciplined environment, utilized aspects of the above to create a military advantage. For instance, Stalin’s infamous Order No. 227, July 28, 1942, “Not a Step Back,” which was to stiffen the spine of Soviet soldiery. No commander had the right to retreat without specifically being ordered to do so.

Known as penal battalions or Shtrafbats, such troops were cannon fodder, as they ran through minefields or assaulted enemy positions prior to regular line troops. Soldiers consigned to such units were considered to have exhibited the less than required intestinal fortitude against the “fascist invader.”

Blocking detachments, formations of NKVD (forerunner of the KGB) lay in wait behind the lines to enforce the compliance of those who retreated. Though it was possible to be reassigned to a regular unit when a candidate had demonstrated that he was ready for such a hoped for transfer.

Upwards of 442,700 Soviet soldiers served in the penal battalions. This, in addition to the fact, that Stalin had some 158,000 shot for cowardice or incompetence. This included 248 generals and admirals, so Stalin did have a more “liberal” view on maintaining discipline. Indeed, Stalin is reputed to have replied, to a question as to the Shtrafbats, that “. . . it took a brave man to be a coward in the Red Army.”

Germany, too, 1944-1945, resorted to young teens when hard up for men. February 1945, Hitler ordered the induction of 6,000 boys, ages 15 to 16, to “beef up the rear defense line.” See page 236, Chapter 9, “The Final Sacrifice,” Hitler’s Children, by Gerhard Rempel. There was also the Werewolves, German youth organized to conduct behind the lines disruption and sabotage, as well as carryout assassinations of enemy soldiers, agents and German “collaborators.” Indeed, on March 25, 1945, the American-installed mayor of Aachen, Franz Oppenhoff, was liquidated by a local Werewolf commando squad. Such squads of Hitler Youth were active to well into 1946. See pages 182-184, Chapter 10, “The End of the Hitler Youth,” Hitler Youth, by Brenda Ralph Lewis.

[10] See page 15, Part I: “The Prelude,” 1: “The Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait,” Military Lessons of the Gulf War, by Bruce W. Watson; Bruce George, MP; Peter Tsouras and B.L. Cyr.

[11] Adolf Hitler returned home, to Austria, March 12, 1938; to which he even brought a large circle of friends for the happy occasion, that being the success of the German Army. Known as Operation: OTTO, the absorption of Austria into the German Reich, is known to history as the Anschluss or annexation, which was in violation of the Versailles Treaty, Section VI, Article 80. To Saddam and other Iraqis, Kuwait was known as the 19th province.

[12] Such contributors as:

Afghanistan: 300 Mujahideen troops (under Joint Forces Command).

Bahrain: 3,500 troops (under Joint Forces Command).

Bangladesh: 2,500 troops (under CENTCOM administrative command).

Czechoslovakia: 350 men, chemical troops and 170 to Saudi Arabia (under administrative command).

Egypt: 40,000 troops, 400 tanks, 600 APCs and 300 artillery pieces.

Kuwait: 7,000 troops (under administrative command).

Morocco: 2,000 troops (under CENTCOM administrative command).

Niger: 400 troops (under CENTCOM administrative command).

Oman: 2,500 troops and 24 tanks (under Joint Forces Command).

Pakistan: 10,000 troops (under Joint Forces Command).

Qatar: 4,000 troops (under Joint Forces Command).

Saudi Arabia: 95,000 troops, 550 tanks (under Joint Forces Command).

Senegal: 500 troops (under ENTCOM administrative command).

Syria: 20,000 troops (under Joint Forces Command).

United Arab Emirates: 4,000 troops (under Joint Forces Command). See page 240, E., Ground Forces, Military Lessons of the Gulf War, by Bruce W. Watson; Bruce George, MP; Peter Tsouras and B.L. Cyr.

[13] See pages 44, 45 and 54, by Major General Robert S. Frix and Major Ronald A. Carter, “Third Army View of Desert Shield/Storm,” Army Aviation, Vol. 52, No. 12, December 31, 2003.

[14] See page 14, “AVSCOM: A Desert Shield Overview,” Army Aviation, Vol. 40, Nos. 3 & 4, March-April 1991, by Major General Donald R. Williamson.

[15] See page 14, Major General Donald R. Williamson.

[16] See page 23, “DESERT SHIELD: The Challenges,” Army Aviation, Vol. 39, No. 11, November 30, 1990, by Colonel Thomas W. Garrett.

[17] See page 12, “Contingency Warfare: Our Strong Suit,” Army Aviation, Vol. 39, No. 10, October 31, 1990, by Major General Rudolph Ostovich, III.

[18] Major General Ostovich, with his wonderfully orchestrated effort of how America must prosecute its military requirements in the post-Soviet era, is also fortifying a reality that has existed since November 25-26, 1950, when 300,000 Chinese troops entered the Korean War, forcing a ceasefire on July 27, 1953, thereby insuring the survival of the North Korean regime; but which also put the finishing touches on Levee en Masse. A period when Army doctrine saw to the destruction of the enemy forces so as to bring the opposing power to the conference table for the declaration of terms. Such was highly successful in 1865, 1918 and 1945.

Of course, beginning with the Bomb, Levee en Masse, conscripting entire populations and economies for war came to a screeching halt, especially in the West, where many populations in the developed world most likely would not show up (just after 9/11 in the United States being an example) for a war. The Great War, 1914-1922; 1931-1945, is largely responsible for this after the horrible harvest of humanity, upwards of some 75,000,000 souls, mostly on the European continent.

General Ostovich notes the necessity of destroying the enemy force, in particular since American troops will most likely field the smaller team. The example here is Genghis Khan’s Mongol Army: Mobility was the key to success, of what was arguably the most victorious army in the history of Man. For upon the defeat of an opponent, his host was pursued and hounded until eradicated; in addition to a finishing stroke applied to the leader himself. Certainly saves the distribution of forces to occupy a territory for the purposes of policing it for cleaning out pockets of resistance.

[19] During Operation BARBAROSSA, Hitler’s overriding concern was the destruction of Stalin’s Red Army, in lieu of taking and holding territory. The Fuhrer understood Napoleon’s failure to hold Moscow in 1812. But this was the Soviet Union of 1941, not France of 1940. The mammoth size of the Soviet colossus helped the Soviet Army survive the Nazi onslaught, as did Russia’s most faithful allies, General Winter and General Mud. A grander analysis, though, is beyond the scope of this work; despite which the point as noted should be readily understood and well taken.

* * * * *

Bibliography

Cordesman, Anthony H., The Iran-Iraq War and Western Security, 1984-1987, Jane’s Publishing, Company, Ltd., London, 1987.

Friedman, Norman, Desert Victory: The War for Kuwait, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1991.

Fris, Major General Robert S. and Carter, Major Ronald A., “Third Army View of DESERT SHIELD/STORM,” Army Aviation, Vol. 52, No. 12, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Monroe, Ct., December 31, 2003.

Garrett, Colonel Thomas W., “DESERT SHIELD: The Challenges,” Army Aviation, Vol. 39, No. 11, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., November 30, 1990.

Judis, John B., The Folly of Empire, A Lisa Drew Book/Scribner, New York, NY., 2004.

Karsh, Efraim, The Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988, Essential Histories, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2002.

Lewis, Brenda Ralph, Hitler Youth: The Hitler Jugend in War and Peace, 1933-1945, MBI Publishing, Company, Osceola, Wisconsin, copyright Amber Books, Ltd., 2000.

Ostovich, Major General Rudolph, III, “Contingency Warfare: Our Strong Suit,” Army Aviation, Vol. 39, No. 10, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., October 31, 1990.

Rempel, Gerhard, Hitler’s Children: The Hitler Youth and the SS, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, 1989.

Rogan, Eugene, The Arabs: A History, Basic Books, New York, NY., 2009.

Tackaberry. Colonel Burt S., “Part I: 24th Aviation Brigade in DESERT STORM,” Army Aviation, Vol. 40. No. 6, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., June 30, 1991.

Vuono, General Carl E., “Training and Readiness: Challenges for Army Aviation,” Army Aviation, Vol. 38, No. 5, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., May 31, 1989.

Watson, Bruce W.; George, Bruce, MP; Tsouras, Peter and Cyr, B.L., Military Lessons of the Gulf War, Greenhill Books, Presidio Press, Novato, California, 1991.

Williamson, Major General Donald R., “AVSCOM: A Desert Shield Overview,” Army Aviation, Vol. 40, Nos 3 & 4, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., March-April 1991.

Looking Back, September 2025

By Mark Albertson

Part II: Army Aviation and its, Magna Carta

December 1961, the 8th Transportation Company (Light Helicopter) and the 57th Transportation Company (Light Helicopter) had arrived in Vietnam. These were followed in January by the 93rd Transportation Company (Light Helicopter). Two developments were evident here: America’s commitment to Saigon; and, the Airmobility Concept was on trial. Only the troops to be shuttled were not going to be American, but instead, those of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Meanwhile events in the United States proceeded apace . . .

. . . with American helicopters and Army aviators deployed, testing a concept without an accepted doctrine, official Washington, it seemed, was willing to accommodate the Army.

At the same time, the Air Force was certainly not ignored by the change in regimes in the White House. 1961 saw an expansion in strategic airlift capability, including an increase in the fleet of C-130s. Cargo versions of the KC-135 tanker, effecting the development of the C-141 cargo transport showed Air Force involvement in Flexible Response.[1] Be that as it may, the Army was wasting no time acting on its Magna Carta.

Also in 1961, Clifton von Kann, recently named Director of Army Aviation, scheduled a briefing with Secretary McNamara on Army Aviation and the importance of tactical aerial assets for the Ground Forces. “McNamara indicated that the briefing helped him to see Army Aviation in a new light and he requested additional paperwork.”[2]

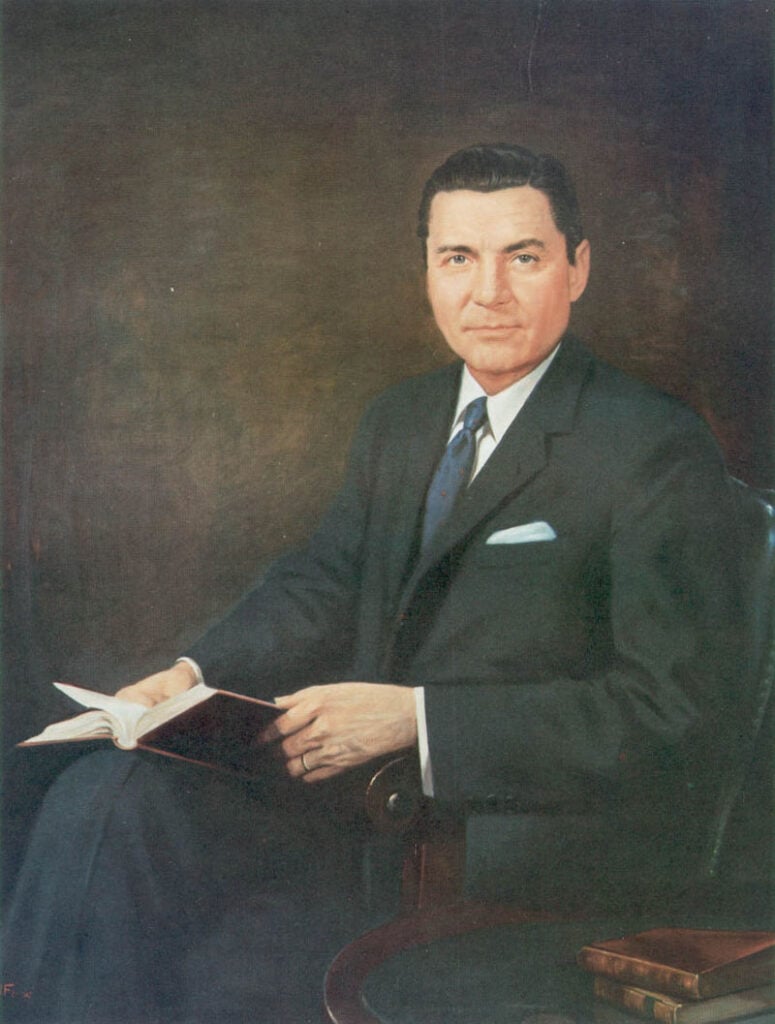

Robert McNamara was the eighth Secretary of Defense, 1961-1968. He served two Presidents: John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. A U.S.A.A.F veteran in World War II, he favored the Army’s use of aircraft for the movement of troops. He ordered the Secretary of the Army, Elvis J. Stahr, to see to it that the Army proceeded in the direction of Airmobility.

A mover and shaker behind the scenes was Robert R. Williams, a West Point grad and a member of the Class Before One and, the first Master Aviator. Williams had been, for all intents and purposes, a political insurgent for the founding principle of Army Aviation, the Air Observation Post.

Following the defeat of the Axis Powers, Williams was sent by the Army Air Forces to Europe, so as to canvass Air Force officers and Ground Forces commanders with regards to the Army Ground Forces retaining their organic aerial assets. “General Hoyt S. Vandenburg for example, felt that such an arrangement would permit the Army to convert its aircraft into close support fighter-bombers and airlift aircraft; others, such as Lauris Nordstad, felt that the atomic bomb had rendered the Army essentially irrelevant.”[3]

Williams, too, was on the McNamara staff and, from the inside, helped to channel the office of the Secretary of Defense towards nodding favorably in the direction of Army Aviation. This resulted in a pair of missives penned by the Secretary of Defense on April 19, 1962:

1) “Memorandum for the Secretary of the Army: Subject: Army Aviation.” And . . .

2) . . . “Memorandum for Mr. Stahr.”

Both directives compelled the Secretary of the Army, Mr. Elvis J. Stahr, to proceed in the fashion outlined above. The latter ordered the Army to take advantage of recent developments in technological advances in aviation to effect improvement in aerial tactical mobility, noting it as a “’bold new look’ at land warfare mobility,” while the former was a more general directive requiring the Army to effect positive changes in tactical mobility.[4]

Secretary of the Army, Elvis J. Stahr, 1961-1962, was a lieutenant-colonel in the Army during World War II. He carried out McNamara’s direction ordering the Army to formalize the Airmobility Concept. Stahr later became the President of the National Audibon Society.

This culminated, of course, in the Tactical Mobility Requirements Board, created by the United States Continental Army Command, May 3, 1962. Total staff amounted to 199 officers, 41 enlisted and 53 civilians.[5]

Lieutenant General Hamilton H. Howze, commander of the XVIII Airborne Corps at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, was pegged to chair what would popularly be known as the Howze Board.

Per the orders of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Hamilton H. Howze will chair the Tactical Mobility Requirements Board, AKA, the Howze Board and formalize in Airmobility in the United States Army.

Per the directive of General Herbert Powell, of the Continental Army Command, the final draft of the board’s findings was to be submitted to the Secretary of Defense by August 20 to accommodate Mr. McNamara’s deadline of September 1. A caveat here, though, was the voluminous nature of the report, which Howze questioned. The Department of the Army asserted that it should be able to fit neatly into an Army footlocker. And, of course, 300 copies were required. To fulfill such a paper chase, the printers at the Adjunct General Department stated that to produce 300 copies of the report that could fit into an Army footlocker demanded that it have the report no later than August 1, so as to accommodate the August 20 deadline. So the window of constraint was quite obvious here.[6]

The Board consisted of a review committee, composed of 17 officers and five civilians; together with an advisory panel with two members and a secretariat. Board secretary to General Howze was Colonel John Norton. Within the body of the memorandum addressed personally to Secretary of the Army Stahr, were individuals named by Secretary of Defense McNamara, who would be on the review committee chaired by General Howze and/or the secretariat: Besides Howze, Brigadier General Delk M. Oden, Brigadier General Walter B. Richardson, Colonel Robert R. Williams, the aforementioned Colonel John Norton, Colonel A.J. Rankin, Mr. Frank A. Parker, Dr. Edwin W. Paxson and Mr. Edward H. Heineman.[7] In addition, the commanding general of The Infantry Center, the special assistant to the Chief of Staff for Special Warfare and Brigadier Edward L. Rowney of the 82nd Airborne Division, were attached to the review committee. The Board would be settled at Fort Bragg in a school facility set aside as the headquarters.

Much of the work associated with the Tactical Mobility Requirements Board was done by seven working committees, from May 5 to June 21, 1962, and were as follows: Operations Research; Field Tests; Tactical Mobility; Firepower; Logistics Operations and Logistics Support; Reconnaissance; Security and Target Acquisition; and, Programs, Policy and Budget. On the heels of which were eight working groups, June 22 through July: Logistics Forces; Combat Force; Counterinsurgency; Strategic Area; Operations Research; Long Range; Field Tests; concluding with, Programs, Policy and Budget.

General Howze was not only President of the Board, but Chairman of the Steering and Review Committee as well. In addition to General Howze, seven other officers and six top level civilians originally composed the Steering Review Committee. These included Major General Ben Harrell, Major General William B. Rosson, Brigadier General John J. Lane, Brigadier General Delk M. Oden, Brigadier General Robert R. Williams, Colonel William M. Lynn, Jr., Dr. Jacob A. Stockfisch, Dr. Edwin W. Paxson, Eugene Vidal, Fred Wolcott, Frank A, Parker and Edward H. Heineman. Mr. Parker, General Rowney and Colonel Lynn also served as chiefs of working committees. Other senior board members (eventually added to the Steering and Review Committees) were named working committee chiefs—Major General Clifton von Kann, Major General Norman H. Vissering, Brigadier General Frederic W. Boye, Jr., and Brigadier General Walter B. Richardson.[8]

“The Air Force sent down a brigadier general to act as a monitor. He was privileged to see all the tests and exercises and could review anyone he chose, but we did not invite him to sit with the steering committee, and all the subcommittees were privileged to exclude him. This, in retrospect, seems regrettable, but in some sensitive areas, frank debate would have alarmed the Air Force and that admirable establishment really needed no additional agitation.”[9]

Perhaps in an effort, though, to foster better service relations, Deputy Secretary of Defense, Roswell L. Gilpatric, on May 8, 1962, that in the support of Army efforts wanted to make sure that air transport was available when requested by the Board. Such as a squadron of C-130s “which would provide the Air Force an opportunity to sell its services and capabilities.”[10]

Howze further explains in his book that in preparation Army Intelligence was petitioned for the latest intelligence on doctrine and capabilities of the Warsaw Pact as well as the People’s Republic of China. Weapons experts, designers and scientists were vetted for weapons types expected for the period 1963-1975, including opinion from the newly minted Combat Developments Command. Robert R. Williams was sent with a team to Southeast Asia to assess the potential of Army Aviation in such an environment; and Army logistics experts, in accordance with civilian equivalents from a dozen aircraft companies to advise on the current capability of the Army aircraft support system and its potential.[11]

Howze, added, that some 400 letters were posted to officers, those on active duty as well as those who had retired, for their expertise. Another 300 letters or more were forwarded to airframe, engine, armaments and electronic firms for their input, creating in essence, a reference source of unquestioned value, as well as being a sales pitch for companies to consider Army Aviation as a viable market.[12]

“Two agencies under contract with the Army, Research Analysis Corporation (R.A.C.) and Technical Operations Incorporation (C.O.R.G.), did studies and analysis for use as requested. Rand Corporation and Stanford Research provided several analysts and scientists for consultation and evaluation of committees at work.”[13]

Computer simulations, together with actual field work, saw Airmobility challenged through four battle models: A Warsaw Pact attack on Western Europe; versus Chinese Communist Forces in Asia (obviously the stalemate of the Korean War was still fresh in the minds of the planners); and, the blunting of threats to Africa as well as Central and South America. And, of course, the Army’s choice of vehicle to carry forward Airmobility . . . the helicopter.

The Howze Board released its finding on August 20, 1962. From the viewpoint of history, a fascinating perspective arises: The Army’s attempt to base Airmobility on the helicopter during the 1960s was not too unlike the transition in mobility from the horse to the truck and tanks, during the 1920s and 1930s. However an important factor to appreciate here was that the United States was not the only power wrestling with mobility during that period leading up to the continuation of the 1914 conflict, sharing the stage with Germany, Britain and the Soviet Union. . . And the living embodiment of the criteria set forth by the Howze Board . . . the 11th Air Assault Division (Test).

* * * * *

11th Air Assault Division (Test)

The resolution of the Tactical Mobility Requirements Board set the stage for that next step in the quest to implement Airmobility. Lieutenant General Hamilton H. Howze urged the conversion of the 82nd Airborne into the air assault division as projected by his committee. He was overruled by Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, who instead authorized an expansion of Army personnel for fiscal year 1964, from 960,000 to 975,000.

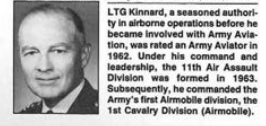

McNamara’s authorization would enable the new unit to be organized from scratch. And on January 7, 1963, orders were issued to commence the operation. The 11th Air Assault Division (Test) was activated at Fort Bragg, North Carolina on February 15, 1963. In command was Brigadier General Harry W.O. Kinnard.[14]

General Harry W.O. Kinnard, commanding officer of the 11th Air Assault Division (Test).

11th Air Assault Division (Test) had its roots in the 11th Airborne Division. The “Angels” were activated on February 25, 1943, seeing action in the Philippines at Leyte and Luzon.

With the cessation of hostilities, the 11th Airborne landed in Japan as part of the postwar Army occupation of the Japanese home islands.[15] The “Angels” were deactivated on June 30, 1958; reactivated briefly on February 1, 1963, then re-designated 11th Air Assault Division (Test) on the 15th.

Among those units attached to the 11th A.A.D early on were those from the 187th Infantry Regiment;[16] as well as the 227th Assault Helicopter Battalion.[17] In addition to the activation of the 11th A.A.D, a logistics support unit was organized in the name of the 10th Air Transport Brigade.[18]

Training focused on air assault; drilling infantrymen on the new concepts of joining combat and engaging the enemy. Provisional supply bases of fuel and stores were made available and organized to keep pace with helicopter units on a fluid battlefield.

Hence the concept of F.A.R.P. or the Forward Arming and Re-Fueling Point.[19]

Another innovation was artillery fire support for landing zones. This included rocket-firing helicopters to support attacks by air assault troops; bolstered, in part, by experience gleaned from Army Aviation support of Army of Republic of Vietnam (A.R.V.N.) units in Southeast Asia.[20]

In September 1963, Air Assault I exercises at Fort Stewart in Georgia, saw the Airmobility Concept put through its paces on the battalion level of operations. The following year, October 1964, Air Assault II was conducted and by comparison, an exercise on a far grander scale.

Air Assault II sprawled across two states, the Carolinas, taking in some 4,000,000 acres. 35,000 troops were committed, with the 11th A.A.D. squaring off against the 82nd Airborne Division; the latter engaged in the role of an enemy conventional force as well as that of insurgent opposition.

The first of the four weeks slated for the exercise was conducted during a hurricane, “Isabel.” Flying conditions were abysmal; a swirling vortex of wind, rain and fog, leaving many aviators peering through windscreens opaque as a bucket of mud.

Yet 120 helicopters managed to shuttle an infantry brigade 100 miles through the ire of Mother Nature.

General Kinnard summed it up thus: Beyond what I believe to be its capabilities to perform roles normal to other divisions, I am even more impressed by what I feel is its ability to perform in unique ways beyond the abilities of other divisions.

For example, in a low-scale war, I believe it can exert control over a much wider area and with much more speed and flexibility and much less concern for the problems of interdicted ground communications or of difficult terrain.