History / By Dario Politella: The term “Grasshopper” is no longer used with pride and affection of World War II days. Army Aviation today also frowns on the term “light” plane because the adjective no longer applies. But some of the old timers of the “organic” air observation for artillery days are still nostalgic over the printable names they were called.

L-4 Piper Cub / Army Aviation photo

“Air OP,”[1] “Flying Jeeps,” “Horseflies,” “Puddle Jumpers,” “Dragonflies,” “Maytag Messerschmitts.” The derivations of these terms are obvious, but just who used what first and how come would make interesting reading.

For example.—During the summer and winter of 1941, light plane manufacturers had been trying to convince the War Department that they could provide aircraft cheap in cost and easy to maintain for field operation with ground units. Ten Pipers, two Aeroncas and two Taylorcrafts, manned by civilian pilots, were attached to field commanders engaging in maneuvers. In November 1941, at Fort Bliss, in the midst of a mock battle, Major General Ennis P. Swift, commander of the First Cavalry, called for “those grasshoppers.

He had seen the little planes flitting from pasture to pasture at tree-top height.—And the name stuck.—It became most appropriate for the L-5 Stinson Sentinel, however, whose fuselage silhouette resembled that of a grasshopper, especially the shape of the tail cone whose streamlining was definitely that of the ovipositor (egg-laying organ) of the insect.

(Any stories about nicknames for AAs [old and young], with sources and dates, will be appreciated for inclusion in this column. Please send your information to Dario Politella, 485 Francis Street, Kent, Ohio).

Endnotes

[1] Air OP or Air Observation Post is actually what was organized on June 6, 1942, not Army Aviation.

Source: See page 27, Vol. 3, No. 3, Army Aviation, March 1955.

. . . the marshal observes that the boldest and most extended plans are generally the wisest and most successful. When we are determined upon war, . . . we should carry it on vigorously and without trifling. Napoleon Bonaparte[1]

* * * * *

President Ronald Reagan sitting in session with members of Congress in discussions with the unfolding situation in Grenada, October 25, 1983.

To the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the prospects for success outweighed the hazards. It was only ten years since the United States had incurred its worst political defeat, thus far, in the twentieth century. So a bold strike would go miles in demonstrating the resiliency of the United States; reassure allies in Europe, the Middle East and Japan. . . ; and, decisive action would show that the American military was a competent, professional armed body and prove the viability of the all-volunteer force.

The JCS urged the White House to establish that legal umbrella that would foster that political acceptability for URGENT FURY. “If possible, the President should consult Congress in advance of the operation as required by Section 3 of the War Powers Resolution; [2] if this was not possible, within 48 hours of the invasion he should explain the necessity and legal grounds for the operation to the lawmakers. In accordance with Article 51 of the UN Charter[3] and Article 5 of the Rio Treaty,[4]the State Department should inform the Security Council of the United Nations and the signatories of the Rio Treaty of the operation and the reasons for it. Since Grenada technically remained a member of the British Commonwealth, the United States should obtain the assistance or at least the approval of the United Kingdom. Finally to legitimize continued military occupation after evacuating the U.S. civilians, a request to form an interim Grenadian government would be needed.[5]

October 22, 1983, intelligence offered that General Hudson Auston was set to mobilize 2,000 reservists to bolster upwards of 1,500 Grenadian regulars and some 600 available Cubans. This caused the JCS to raise troop strength for the operation. A larger combined force of Marines, Army Rangers, Airborne troops and JSOC, would be committed when operations commenced on October 25th.

October 23, 1983, per the invasion plan, USS Independence (CVA-62) and its battlegroup was to take station forty miles north of Grenada. Six hours prior to the assault, JSOC teams and Army Rangers would fly out of Pope Air Force Base, North Carolina, and Hunter Army Airfield, Georgia.[6]

Next, seaborne assaults and helicopter insertions of Special Operations units would precede the main bodies of Marines and Rangers to seize the airfields at Point Salinas and the Pearls. Once the airfields, government buildings and significant military targets had been neutralized, American citizens were to be rounded up and evacuated. Too, British Governor General Scoon and foreigners were to be assured of safe conduct. Peacekeeping forces from the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States were to be airlifted in to assist U.S. forces in peacekeeping duties, with Governor General Scoon to organize an interim government.

* * * * *

On October 22, Lieutenant Colonel Wesley B Taylor, Jr.’s, 1st Battalion of Rangers, 75th Infantry, at Hunter Airfield in Georgia, was alerted. Rousted, too, the following day at Fort Lewis, Washington, was 2nd Battalion of Rangers, 75th Infantry, Lieutenant Colonel Ralph L. Hagler in command. These units had been trained in the seizure of airfields. They were to be conveyed by C-130s for a parachute drop onto Point Salinas Airfield.

Readied at Fort Bragg was Colonel Stephen Silvasy, Jr.’s 2nd Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division, and was bolstered by 2nd Battalion, 325th Infantry (reinforced by a company from the 2nd Battalion, 505th Infantry, 3rd Brigade) and was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Jack L. Hamilton. This order of battle was rounded out by 3rd Battalion, 325th Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John W. Raines.[7]

Assistance was rendered by the XVIII Airborne Corps; which had been, up to now, excluded from the planning stages or considered part of the command staff. Departure was arranged from Pope Air Force Base. Insertion into the zone of operation was to be by parachute drop. Conveyance was by C-141 Starlifters. Silvasy’s troops were to enter the fray after the operation had commenced. They lifted off on the morning of the 25th, with the C-141s made ready for the parachute drop while on the way to the target, Point Salinas Airfield.[8]

Endnotes

[1] See page 7, MAXIM V, Napoleon’s Art of War, Translated from the French by Lieutenant General Sir G.C. D’Aguilar, C.B.

[2] Section 3, “Consultation,” War Powers Resolution: “Sec. 3. The President in every possible instance shall consult with Congress before introducing United States Armed Forces into hostilities or into situation where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by circumstances, and after every such introduction shall consult regularly with the Congress until United States Armed Forces are no longer engaged in hostilities or have been removed from such situations.

[3] Charter of the United Nations: Chapter VII—Action with respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression. Article 51: “Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security. Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defense shall be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and security.”

[4] Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (Rio Treaty), September 2, 1947. “Article 5: The High Contracting Parties shall immediately send to the Security Council of the United Nations, in conformity with Articles 51 and 54 of the Charter of the United Nations, complete information concerning the activities undertaken or in contemplation in the exercise of the right of self-defense or for the purpose of maintaining inter-American peace and Security.”

[5] See page 25, Chapter 2, “Planning and Preparation, 21-24 October, 1983,” Operation: URGENT FURY, Grenada, by Ronald H. Cole.

[6] See page 29, Ronald H. Cole.

[7] See page 12, “Preparations,” Operation: URGENT FURY, The 1983 Invasion of Grenada, by Richard W. Stewart.

[8] See pages 13 and 14, Stewart.

Next month, Part III, “The Battle.” Bibliography will be included at the end of Part IV.

Historical Perspective – Part 1 / By Mark Albertson: Thaddeus Lowe lifted off from Cincinnati, Ohio. This was a trial flight preparatory to a grander effort of aeronautical significance… Europe, via a lighter-than-aircraft across the Atlantic which required a better understanding of the jet streams and how to cope.1 For his test flight, Lowe chose his balloon, Enterprise.2

The 16th President, Abraham Lincoln, supported the idea of aerial observation and reconnaissance in the Union Army and, was a supporter of Thaddeus Lowe./ WIKIPEDIA COMMONS PHOTO

Lowe’s quest ended prematurely, as he was blown off course, due south, into the Confederacy. He came to earth in Unionville3, South Carolina. He and his balloon were taken to nearby Columbia, where fortunately, southerners acquainted with Lowe and his aeronautical exploits were able to help him and his balloon be returned to Cincinnati; as opposed to being jailed or worse, perhaps convicted of spying for the Union.

He was “permitted to return to Cincinnati by way of Columbia, South Carolina and Louisville, Kentucky. “As he traveled through the South he became increasingly convinced that the war would be long and arduous, and he determined to organize a balloon corps in the Union and to offer his services as a military aeronaut.”4

Such services for the Union would entail the most subdued form of aeronautics; that of the tethered balloon as opposed to his experiments with the jet stream and free flight.

Murat Halstead, editor of Cincinnati’s the Daily Commercial informed Lowe that he would pass along his offer for his aeronautical services to Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon P. Chase.

Aeronaut, Thaddeus Lowe, first to electronically transmit

a message, by telegraph,

from an aircraft (balloon) in the air to receiving stations on the ground.

But other aeronauts were seeking favor with the federal government as well, with their own approaches for aerial observation and reconnaissance. James Allen, John Wise, John La Mountain, all had entered the field first, contacting different officers in the Union Army and various government officials, all trying to make their pitch. Thaddeus Lowe, though, sought the inside track with an approach, reputedly never before attempted by any other aeronaut, with the use of a modern electronic device emblematic of modern communications in the 19th century… the telegraph.

Lowe planned to equip the balloon basket with a telegraph. His plan called for battery-powered telegraphy. Connection to the ground was to be by wire, running from the basket, down the static lines securing the balloon to the earth. Joseph Henry, a physicist by trade, grasped the concept straight away. For Henry, himself, had figured prominently in the “invention of electron magnets and relay junctions introduced into modern telegraph systems decades before.”5 To Henry, such a technological advance as electronic communications successfully implemented from an aerial platform for such military purposes as observation and reconnaissance could prove decisive.

Lowe’s next stop was the Department of the Treasury, with Mr. Salmon P. Chase. The meeting was brief. Chase, too, seemed supportive and assured the aeronaut that he would see to his plan with the president personally. And on June 11, Secretary Chase’s office informed Lowe that the President would have audience with him that evening.

Lowe proceeded to the White House, together with Joseph Henry from the Smithsonian, who acted as his sponsor and witness to Lowe’s technical and scientific skills. They were graciously received by the President. “Lincoln listened attentively to the proposals of the two men and expressed a decided interest in the possibilities of balloons for war service. “The interview was concluded with the President’s promise of serious consideration of the plans laid before him.

“Shortly thereafter, the War Department appropriated a sum ‘not to exceed $200 or $250’ for Lowe’s use in carrying out tests and demonstrations. “. . . and by June 13, most of the details had been settled.”6

Despite assurances from the President, and the promise of money from the War Department, of which $250 was appropriated, confidence in Lowe’s endeavors was not shared by all participating parties. Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, was hardly enthusiastic, when James Allen was already working with the Army. Indeed . . . “On June 9, 1861, Allen prepared the larger of his two balloons for inflation under the supervision of Major Albert Meyer, the Union Army’s chief signal officer.”7 “Brigadier General J.F.K. Mansfield, then commanding the Department of Washington, was reported much interested in the matter.”8

Emblematic of much of the reactionary thinking in the Union Army was that of the Commander-in-Chief, himself, General Winfield Scott; that, in response to the efforts then presently underway to organize aerial observation…

“…on June 14, Captain A.W. Whipple of the Topographical Engineers informed his chief, Major Hartman Bache, that ‘the General thinks a balloon of little use in this section of the country.”9

Lowe’s attempt at aerial electronic communication to the ground was a gamble… on which rode the fortunes of the Balloon Corps.

Endnotes

1. See pages 161 and 162, Chapter V, “The Early Career and Work of T.S.C. Lowe, Chief Aeronaut of the Army of the Potomac,” Aeronautics in the Union and Confederate Armies, by F. Stansbury Haydon.

2. The name Enterprise was used for aircraft, beginning with the balloon, L’Entreprenant, Jean Marie Coutelle, French Company of Aeronauts or Compagnie d’Aerostiers, 1794. To Lowe’s Enterprise during the War Between the States to starship Enterprise, commanded by Captain Kirk, Star Trek. See page 31, Chapter 3, “Lowe Flying,” Balloons at War, by John Christopher.

3. Later shortened to Union.

4. See page 4, Chapter 1, “Balloons and Airships in the United States Army, 1861-1913,” The United States Army Air Arm, April 1861 to April 1917, by Juliette Hennessey.

5. See page 66, Chapter Four, “Creating an Army in the Air,” War of the Aeronauts, by Charles M. Evans.

6. See pages 171 and 172, F. Stansbury Haydon.

7. See page 64, Evans.

8. See page 173, Haydon.

9. See page 173, Haydon. F. Stansbury Haydon was referring to, a “War Department document in the National Archives [hereinafter cited as LRTE]. Whipple to Bache, June 14, 1861, MS W506, Letters Received, Bureau of Topographical Engineers.”

Mark Albertson is the award-winning Army Aviation Publications Historian and a contributing editor to ARMY AVIATION magazine.

Army Aviation History / By Mark Albertson: The invasion of Grenada was a modern version of siege warfare. Cuban defenders were isolated, with no hope of relief. Reminiscent, in part, of the island-hopping campaign in the Pacific Theater, 1942-1945.

The Pacific Theater of operations was emblematic of a naval version of siege warfare; a version of naval warfare certainly possible as the Pacific Fleet rebounded from the drubbing incurred at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. And by 1943, the U.S. Navy was able to neutralize the Imperial Japanese Navy. Garrisons on Japanese island outposts that were bypassed were left to wither on the vine; while besieged garrisons facing certain assault were left to their own devices.

Grenada and its strategic position in the Caribbean.

First and foremost, the Grenada operation was an example of control of the sea, a number one prerequisite for victory. The Royal Navy proved this the year before, 1982, at the Falklands; as did the U.S. Navy with Operation: WATCHTOWER, Guadalcanal, August 7, 1942 to February 3, 1943. Yet . . .

. . . it has been stated by some, that the post-Vietnam, all-volunteer Army saw its validation and endorsement with Operation: DESERT STORM, January 1991. Yet seven years prior to the preparatory phase of serving Saddam Hussein his eviction notice from Kuwait, known as Operation: DESERT SHIELD, Army Aviation had already achieved that stature of an official branch in the United States Army. This was followed, six months later, by the first official combat action by Army Aviators under the auspices of branchhood . . . Grenada. URGENT FURY, then, was that coming out event in the post-Vietnam era for Army Aviation, as well as the all-volunteer Army.

Point Salinas airfield, cause of concern in Washington as a strategic asset for Havana and Moscow for control of the Caribbean Sea.

the Caribbean, the repeat of history was evident. Accent on the post-Vietnam period was to prepare Army Aviation for a conventional/nuclear warfare approach to countering the threat posed by Soviet tank armies in Europe. This was rerun of the Post-Korean War era, in which a dwindled Army Ground Force was being trained to fight on a nuclear battlefield in Europe, employing the helicopter to disperse and then gather the troops for battle. But Grenada, like Vietnam—and let us not forget Korea—in which Army Aviation was thrust into an environment in which the Airmobility concept was proven on the field of action, but again on a battlefield hardly conducive to the conventional variety that was supposedly to be found in Europe.

Indeed, the ability to successfully perform in environments other than what it was organized for, underscores the ambidextrous nature that seems to be inherent in Army Aviation; in other words, the ability to adapt. The talent to accommodate the fluctuating aspects of war renders Army Aviation a valuable tool in the American toolbox for preserving or asserting the Nation’s interests. For the year is 1983. The Soviets are learning, too; well on their way towards acclimating airpower, and in particular, the helicopter to combat the Mujahideen; a preview of what Army Aviation would later be doing in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Yet a salient point from an historical perspective in the West here is, the Industrial Revolution is over, having given way to the Technology Revolution. Industrialized, corporatized, commercialized conflicts that characterized war in the first half of the 20th century, are no longer the order of the day. Levee en Masse, the conscription of entire economies and populations for war seems, at this juncture, to be a thing of the past; that the conscript, who dominated warfare, from the end of the 18th century to 1945, has given way to the volunteer and/or professional soldier, such was what followed the Thirty Years War in Europe, from 1648 to 1793.

This four-part series on Operation: URGENT FURY, will take a look at a little regarded military operation and Army Aviation’s part in same. At the same time, it will provide a peak into a major power’s attempt to rebound following its embarrassing political defeat in Southeast Asia.

* * * * *

Prelude

The wreckage of an American helicopter, with an abandoned RH-53D, from the failed rescue attempt at DESERT ONE in Iran, was recalled when planning the rescue and evacuation of American students in Grenada.

1979 was a year of significance. Just six years after the United States’ defeat in the Second Indochina War, Washington’s satrap in Tehran, Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, had been dethroned, with the resulting void being filled by a Shia Fundamentalist regime, led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. December that same year, Soviet forces rolled into Afghanistan to bolster the Moscow-backed government of Socialist Orientation in Kabul.

In Iran, though, a political situation arose, and one of an extremely sensitive nature, that being the takeover of the American embassy in Tehran by anti-American malcontents. This would foster the failed rescue attempt of the beleaguered American diplomatic personnel. Yet the tragedy at DESERT ONE hardly boosted confidence in the prowess of the American military, in the wake of the defeat in Southeast Asia.[1] And this, in addition to the fact, that in Beirut, 1983, more than 200 Marines were lost to a terrorist attack on their barracks. President Ronald Reagan would eventually remove the American contingent.

In 1979, too, Maurice Bishop came to power in Grenada. Concern quickly arose in Washington that Grenada was sidling up to Havana and Moscow.

USS Independence (CVA 62), named flagship of the naval battle group for Operation: URGENT FURY.

The Bishop Government was the Revolutionary New JEWEL or New Joint Effort for Welfare, Education and Liberation, considered a Communist-style of government which sought the support of Cuba and the Soviet Union. In so doing, Bishop erected his regime at the expense of the elected government of Sir Eric Gairy.

Affiliation with Soviet Russia and Cuba, aid—both military and trade—in addition to advisors to Grenada, was an effort to produce a satrap of strategic significance.

First, the Grenadian military consisted of a core known as the People’s Revolutionary Army, some 300 men. These were bolstered by half-trained types, the People’s Revolutionary Militia, perhaps numbering a thousand men. Followed by a Coast Guard comprising several fishing boats converted for the task.

Military punch was provided by eight Soviet BTR-60 amphibious personnel carriers, together with a pair of BRDM2 amphibious scout cars, all mounting 14.5 mm machine guns.[2]

The diminutive Grenadian armed forces were bolstered by, and what must be construed as being the center piece of the island’s defenses: The seven hundred Cuban laborers working on an airfield for Havana and Moscow. These “laborers” were Cuban Army reservists; therefore, having a double function, construction and defense.

The construction of a 9,000 foot runway at Point Salinas on the southwestern tip of Grenada, was viewed in Washington as a strategic airfield for Russia and Cuba. Mig-23s could operate from the airfield, enabling competition with Washington for control of the Caribbean; therefore, interdicting tanker traffic north from Venezuela as well as that coming up from the South Atlantic from the Middle East. And with Grenada, since it was more than 500 miles further east across the Atlantic, could prove an important logistics base for Cuban operations in Africa; as well as facilitating flights to and from Libya.[3]

The political situation on Grenada became uncertain on October 12, 1983. Maurice Bishop, having visited Washington, D.C. to meet with U.S. officials, was seen as a liability to the more radical faction within JEWEL. Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard, together with General Hudson Auston, backed by the Central Committee of the government, decided to unseat Bishop and his supporters.

Bishop and other members of his government were held in detention for a week, before crowds of Grenadians gathered. They marched on Mount Wheldale, where Bishop and his entourage were in custody at the Prime Minister’s residency. Once freed, Bishop led the aroused citizenry to army headquarters at Fort Rupert. Here the guards were overpowered. But before Bishop and his supporters could assert their control, Hudson Auston met the threat with troops supported by armored vehicles. An indeterminate amount of Grenadians were killed.[4]

Bishop and his supporters were rounded up. Maurice Bishop was among those executed, as well as Jacqueline Creft, the Minister of education. General Auston proclaimed the Revolutionary Military Council, to which he would head a new interim government.

On October 20, Fidel Castro condemned the actions of the plotters, calling into question their motives. Concerned, too, with the threat such actions could pose on Cuba’s influence on the island. Meanwhile, a 96-hour curfew had been imposed on Grenada; with those violating same liable to being shot.

The curfew imposed a hardship on American citizens and students, including getting needed supplies of food and water, in addition to not being able to leave the island.

Concerns grew in Washington that Auston’s government could pose a dire threat to Americans on the island; in addition to the aforementioned strategic concerns which remained firm. And so on October 19, 1983, the Joint Chiefs of Staff forwarded a warning order to Admiral Wesley L. McDonald, commander U.S. Atlantic Command, for possible evacuations of Americans from Grenada.

* * * * *

Washington Begins to Move.

The presence of armed Cubans on Grenada presented a wrinkle with regards to any evacuation plan. The same day Castro condemned the actions of General Auston, deputy national security advisor, Rear Admiral John M. Poindexter, assembled a pre-planning committee to look into the unfolding crisis. A suggestion brought forth was that of Vice President George H.W. Bush should be given authority to manage the crisis; a recommendation seconded by President Ronald Reagan.

First order of business saw the Joint Chiefs of Staff draft a plan for the evacuation operations, one that would be opposed by Grenadian and Cuban hostiles ashore. Second, it was urged that the aircraft carrier battle group centered round USS Independence (CVA-62) be sent to Grenada, together with a Marine amphibious group. Meanwhile, the XVIII Airborne Corps at Fort Bragg, was to ready the 82nd Airborne Division for potential operations on Grenada.

The night of October 21-22, Eugenia Charles, Prime Minister of Dominica and, Chairman of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, formerly requested the intervention by the United States into Grenada. This was followed on the morning of the 22nd by National Security Advisor, Robert C. MacFarlane, who notified President Reagan of Prime Minister Charles’ request, to which the president concurred. At the same time, preparations were proceeding apace for a joint Army, Marine and Special Forces operation on Grenada.

October 23, 1983, Atlantic Command ordered Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf III, of the U.S. Second Fleet, to command Joint Task Force 120; and as such, would become overall commander of the forthcoming operation. Meanwhile a pair of plans were quickly formulated:

The first scheme saw 1,800 men—Army Rangers together with JSOC contingents or a battalion of Marines supported by SEALs. Here five C-130s would drop the JSOC contingents at night at Point Salinas on the Southwest tip and the Pearls, halfway up the East Coast. These troops, covered by four helicopter gunships, would seize the airfield. In addition, they were to seize the police headquarters and radio station in the capital, St. Georges, as well as grab the Grenadian military barracks at Calivigny. This would all be followed by 16 C-130s landing at Point Salinas and the Pearls with the 1st and 2nd Ranger Battalions. This would consolidate the objectives and mop up any enemy troops escaping into the hinterland.[5]

The second plan featured an amphibious-heliborne operation bolstered by Army Rangers. This effort would be preceded by the SEALs, who would be sent ashore after midnight on the 24th, at Point Salinas, as well as the medical school in St. George’s and the Grand Anse beach, some two miles away from St. George’s. And, the Marines were to grab control of the barracks at Calivigny. Once the Marines had captured their objectives, Army Rangers were to land at Point Salinas and dash for St. George’s to seize the police headquarters, army headquarters and all government buildings of consequence.[6]

* * * * *

Fraught With Political Risks

URGENT FURY was fraught with political risks. The presence of American invasion forces could prompt General Auston and even the Cubans, to take American students hostage or even kill them.[7] Cuban labor units could join Grenadian defenders and cause “unacceptable” American casualties. Would this enable Moscow to engage in political machinations in the Middle East? Asia? Europe? Too, there were the potential backlashes from Congress; the media; foreign governments, whether friendly or otherwise. And notwithstanding, beyond the possibility of unacceptable casualties, there was the potential of a public fallout should American students by injured or worse . . .Yet . . .

. . . War can never be separated from political intercourse, and if, in consideration of the matter, this is done in any way, all the threads of the different relations are, to a certain extent, broken, and we have before us a senseless thing without an object.[8]

Endnotes

[1] Defeat in the Second Indochina War was political, not military. Not to discount the reality, here, of the staggering effects of a political defeat; followed by the concerted efforts, by a number of concerned officers, to revamp the American military for the post-Vietnam period. Included, here, too, is what will follow the debacle of DESERT ONE. This, in turn, will push the military to correct this set back with organizing America’s Special Forces for such operations in the future. Again, the military is acclimating itself to the post-Vietnam War era.

[2] See page 7, “Strategic Setting,” Operation: URGENT FURY, by Jeffrey J. Clarke.

[3] In addition to the aforementioned strategic concerns, there was Soviet support for the Sandinistas in Nicaragua; the insurgency in El Salvador supported by both the Soviets and Cubans; and the FARC insurgency in Columbia.

[4] Estimates vary, from 10 to as high as 100.

[5] See page 23, Chapter 2, “Planning and Preparation, 21-24 October, 1983,” Operation: URGENT FURY, Grenada, by Ronald H. Cole.

[6] See pages 23 and 24, Ronald H. Cole.

[7] The previous hostage crisis in Tehran involving American embassy personnel and the Carter Administration’s failed response to same was not far from the minds of planners in Washington, D.C.

[8] See page 402, PLAN OF WAR, Chapter VI, “(B) War as an Instrument of Policy,” On War, by Carl von Clausewitz.

Complete bibliography to be included at the conclusion of Part IV of this series.

2106_grenada-map.png

Grenada and its strategic position in the Caribbean.

2106_pooint-salinas

Point Salinas airfield, cause of concern in Washington as a strategic asset for Havana and Moscow for control of the Caribbean Sea

2106_uss-independence.png

USS Independence (CVA 62), named flagship of the naval battle group for Operation: URGENT FURY.

2106_BTR-60.jpg

The Soviet BTR-60 armored personnel carrier, which formed the ‘offensive punch’ of the diminutive Grenadian Army.

2106_desert-one.jpg

The wreckage of an American helicopter, with an abandoned RH-53D, from the failed rescue attempt at DESERT ONE in Iran, was recalled when planning the rescue and evacuation of American students in Grenada.

Army Aviation History / By General Hamilton H. Howze, U.S. Army (Ret.) — Source: Pages 53-56, Army Aviation, Vol. 25, Nos. 8 & 9, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., August-September 1977. / Edited By Mark Albertson

I have in the recent past, visited both the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions. In both cases I was much impressed by the appearance of officers and men: Lean, sturdy, smart looking soldiers, alert and neatly uniformed.

General Hamilton H. Howze

In each case also the division staffs were good enough to brief me on what they considered probable division overseas missions on certain international contingencies. In both cases the use (or non-use) of light aircraft was of obvious applicability: the numbers available and their employment would in large measure determine the outcome of the battle. And I came away from those briefings with an uneasy feeling that the Army has in some major respects forgotten much of what it once knew about airmobility.

It is true, of course, that the Army is spending lots of money to develop and bring into production two new helicopters, the UTTAS and the advanced attack helicopter. This is undeniable progress, but the quantities intended for purchase are not impressive, and neither are the number and size of units that are to be equipped with them.[1]

We ended the Vietnam War with two airmobile divisions; we now have one, and that one faces major cuts in strength. We have only one so-called air cavalry combat brigade, which is really not air cavalry but an aerial tank-destroyer force. It has considerable capability in that role, but along with the airmobile division it also may feel the chop.

I recently had access to the Army’s new operations manual, FM 100-5. There is periodic acknowledgment therein of the usefulness of light aircraft, but it is a patch job, with paragraphs apparently being added to an earlier but recent version. Quite obviously Army Aviation is not contemplated in the manual as a basic tool—as a strong, added, available and sometimes decisive capability, as it emphatically should be.[2]

The Answer: “Nothing.”

And a few months ago I talked to a number of young officers who were just graduating from the Advance Class at the Artillery School. I asked the group what the course had included about the techniques of artillery support of airmobile operations. The answer: nothing.

General Howze’s concern was that the Army was disregarding much of what it had learned about Airmobility./Army Aviation Magazine

I am guessing now, but I venture to say that Fort Sill has developed no special technique for the purpose. I am not guessing when I say that such a technique will be different from the normal, will require special training and will be very applicable to the winning of battles.

Because of the foregoing, because of periodically expressed concern about helicopter vulnerability, because of a pronounced dwindling of what used to be an enormous enthusiasm in the Army for airmobility and its practice, and because of current emphasis on the ground mechanization of practically everything, I think the Army is engaged in the implementation of a monumental error in judgment.[3]

We are, in the words of George Patton, taking too much counsel of our fears, and in consequence wrapping ourselves in armor and thereby losing flexibility and a big part of mobility. The helicopter is as vulnerable as a calf to a tiger if one employs it foolishly, but vulnerability will drop to acceptable levels if it is used cleverly and in conjunction with other weapons that can help it.

But given the tank and the armored personnel carrier, do we really need the helicopter as a combat vehicle? Sometimes a question can be answered best by a return to fundamentals. And the fundamental truth is that battles are won by a combination of firepower and mobility, and when the two get out of balance the result is a relatively ineffective fighting force.

Firepower has grown enormously since World War II, mobility much less so unless the helicopter is employed. Tanks and armored personnel carriers move at about the same rate as they did 30 years ago, and the act simply of providing more of them does not provide a given unit—say an armored or mechanized force—much more mobility than it had before.

But what can the helicopter do? I list a few things, things apparently overlooked now by much of the Army:

It can provide unparalleled battlefield mobility. It is an obstacle crosser; natural obstacles such as mountains, cliffs, rivers, dense forests, swamps, lakes and wadis; and artificial ones such as mine fields, contaminated areas, demolitions, artillery fire-swept areas, barbed wire and, on occasion, even enemy positions. Most battlefields are an agglomeration of obstacles. And only the helicopter can cross them quickly and easily—and substitute 140 miles an hour for 10 or 15.

It can provide surprise, often the key to victory, by the very quick and totally unpredictable shift of troops and firepower from one place to another.

It can provide, as nothing else can, very exceptional observation of battlefield terrain.

It provides a highly mobile and elusive platform for very powerful weapons.

It has excellent communications, and can serve as a very efficient messenger during radio silence or when radio frequencies are jammed.

Airmobility mainstay: The UH-60 Black Hawk, the Utility Transport Aircraft System replacement for the UH-1 Huey.

I must guard against overstatement, but I must say nevertheless that the helicopter is a magic machine. Given its unique capabilities and the ‘multi-quantum’ (if that’s an admissible expression) jump it provides in most of the essential and useful qualities of a military machine, it is simply inadmissible to dismiss it on the grounds that it may be shot down.

The approach must be to determine, by intense and frequent practice, how to use it properly. It is certainly unnecessary to specify that the helicopter must not be subjected to enemy fire, but it is true that a major part of its usefulness can be exploited without doing so. And when it must be exposed much can be accomplished by artillery and other weapons in protecting its flight path—if we learn now.

Right after the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, General Peled, the Chief of Staff of the Israeli Air Force, was quoted by the unbelievers as saying that the helicopter could not be employed at the edge of the battle on the Suez Canal. No doubt he was right—neither could any kind of aircraft, including fighters, in the extremely intense anti-aircraft environment that prevailed had the front moved a few miles to the east or west, as it was about to do when the cease-fire came.

Shortly after the war General Peled came to the United States. Why? To buy helicopters, particularly Cobras, for the Israeli Air Force.[4]

In its report issued in the late summer of 1962 the Army’s Tactical Mobility Requirements Board, sometimes known as the Howze Board, recommended that successor but smaller boards be convened every year to reexamine the Board recommendations and to see how things were going to the expansion of what the Board called an almost revolutionary development in ground battle tactics.

I would recommend now that this be done as soon as practically possible, because the action is exactly 14 years overdue, the new Board should do more than just a review; I would hope that it might be blessed by an almost unrestricted charter, as ours was. The Board should draw on the best tactical minds in the Army, on the other services, on operations analysis contractors, on industry as applicable, and on whatever other talent it might find, as ours did. The Board should be provided the terrain and the means to experiment informally with equipment and organization to its heart’s content, restricted only by time and, of course, reason, as ours was.

The Board’s chief purpose should be to bring airmobile doctrine up to date in view of new developments in aircraft and weapons, ground and airborne. New statements on feasibility and vulnerability are necessary—what will work and what won’t, and what tactics and techniques are necessary to take advantage of the helicopter’s enormous mobility and flexibility at acceptable rates of loss.

The Board should determine and recommend an optimum organization for the air assault division, and how many the United States should have. We habitually make the decision on the basis of 16 active Army divisions, forgetting the Marine divisions, the National Guard and Reserve divisions, and the fact that anywhere we fight overseas—Europe, Korea, the Middle East—we will be fighting alongside other and all non-airmobile divisions of our allies, wherefore the United States should have a disproportionally large number of airmobile forces.

I would hope also for a reconsideration of the air cavalry brigade, which I contend should be a homogeneous unit based on a platoon consisting of scout helicopters, two squads of riflemen riding in UTTAS or Hueys, and a couple of armed helicopters. This would be an extremely powerful little force, capable of enormous range of missions: reconnaissance, delay, rear area surveillance and protection, raids, the protection of a long flank, pursuit and exploitation, anti-tank action and others. In a desert area it could keep a couple of hundred square miles under constant surveillance, and effectively delay the progress of an enemy ground unit twenty times its size.

Each troop in my suggested brigade would have three identical platoons, each squadron three identical troops, and the brigade three identical squadrons. I believe each corps of our Army should have such a brigade. Given the assistance of artillery and engineers such a brigade could delay an assault by a Soviet armored corps—giving up ground slowly, meanwhile inflicting heavy damage—better than any reinforced armored or mechanized division in the world.[5]

Tree Tops: A Russian Orb!

And finally the Board’s activities should conclude with a walloping big demonstration to show the DOD, the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, and the Marines what can be done. If I may be permitted to boast, our demonstration in 1962 was impressive not only because it was quick and violent but also because it was convincing. None of the scores of senior officers who saw it ventured to attack it on the grounds of feasibility.

Let me conclude with the apology due from a man 12 years out of the active Army. But I cannot escape the conviction that the Army has not pursued with vigor the development of a highly useful capability at the same time that the Russians, once far behind us in equipment, doctrine, tactics and technique, are borrowing from our experience and markedly improving their ability to exploit that shallow but critically important layer of atmosphere just above the tree tops.[6]

Endnotes

- As a disciple of Clausewitz, Howze’s remarks here, in this short paragraph, should be considered pertinent, dealing as they do with a criticism of numbers, mass. . . Note Clausewitz himself:

“The best strategy is always to be very strong, first generally then at the decisive point. Therefore, apart from the energy which creates the Army, a work which is not always done by the General, there is no more imperative and no simpler law for Strategy than to keep the force concentrated. No portion is to be separated from the main body unless called away by some urgent necessity. On this maxim we stand firm, and look upon it as a guide to be depended upon. What are the reasonable grounds on which a detachment of forces may be made we shall learn by degrees. Then we shall also see that this principle cannot have the same general effects in every War, but that these are different according to the means and end.

“It seems incredible, and yet it has happened a hundred times, that troops have been divided and separated merely through a mysterious feeling of conventional manner, without any clear perception of the reason.

“If the concentration of the whole force is acknowledged as the norm, and every division and separation as an exception which must be justified, then not only will that folly be completely avoided, but also many an erroneous ground for separating troops will be barred admission.” See pages 276 and 277, Chapter XI, “Assembly of Forces in Space,” On War, By Carl von Clausewitz.

- Reminiscent, too, of the prevailing thought by man, of the tank as an infantry support vehicle, as was the case on the Western Front in France. But what the British and French produced were pop-bellied stoves able to troll a battlefield at 3 or 4 miles-per-hour. And depending on the terrain, these underpowered tracked sloths even had problems keeping pace with the walking infantry they were assigned to support. Later models, boasting on-road/off-road capabilities of 30 mph+, suitable armor and a competent gun and a trained crew, brought to the table something obvious to such people as Sir Basil Liddell Hart, J.F.C. Fuller, Charles de Gaulle, Heinz Guderian, especially when one mates the modern iron steed with the decisive Mongol cavalry tactics of the 13th century. For arguably, the mounted Mongol armies were the most successful military force in the entire history of Man due to their . . . Mobility.

- Precisely the criticism rendered by General James M. Gavin, of the U.S. and UN armies in North Korea in the fall and winter of 1950-1951. Armies practicing mechanization in an environment with a distinct lack of an infrastructure of viable roads. Therefore, an entire army riding in modern tanks and trucks was sent reeling by an enemy force (300,000 “volunteers” of the People’s Army of China) moving with the oldest mode of mobility in the history of Man, by foot, because this army assumed control of the countryside. Vietnam proved that with the helicopter, an army can control a countryside. Too . . .

. . . Napoleon can be added here as well with a point for contemplation: “Artillery is more essential to cavalry than to infantry, because cavalry has no fire for its defense, but depends upon the sabre. It is to remedy this deficiency that recourse has been had to horse-artillery, Cavalry, therefore, should never be without cannon, whether attacking, rallying or in position.”

This translates, of, course, in the modern sense, to the attack helicopter and/or ARA as used in Vietnam. See page 75, “Maxim LII,” Napoleon’s Art of War, by Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Reinforcement is not out of order here. While detractors of the helicopters might have been correct here, that it being vulnerable at the front, especially with the measures taken by the Egyptians to bolster air defenses for their armored thrusts, apparently General Peled of the Israeli Air Force was open-minded enough to believe that the attack helicopter had a place in a combined arms approach to dealing with an armored/mechanized threat.

- What General Howze is alluding to here, an airlifted brigade in every Army corps, to which he outlines its tasks, was alluded to, in a fashion, by James M. Gavin, in Harper’s magazine, twenty-three years earlier, 1954. Gavin offered telling criticism of the U.S. Army/UN invasion of North Korea, fall of 1950, a mechanized advance by which much of the forces were consigned to the poor road infrastructure of North Korea. The massive Chinese counterstroke saw a UN/U.S. retreat down the few roads available, pursued and outmaneuvered by an enemy moving by foot and in control of the countryside.

General Gavin offered that a competent mobile force, shuttled by light aircraft and helicopters, could seize and hold bridges and road junctures, attack the flanks and even the rear of the attacking enemy force, protect the flanks of the retreating friendly army, reconnaissance and/or observation, perhaps even direct supporting artillery fire.

- General Howze is quite correct that the Army should have conducted another Tactical Mobility Requirements Board, after a fourteen year hiatus. Perhaps consideration should have been given, too, to convening a major gathering every ten years, so as to critically study the pervious ten years and actively update doctrine, tactics, equipment. . . For the Army is no different than any other institution. It is made up of men. And as the human condition, shows, it gets apathetic, careless and opposed to change. The penchant to become reactionary is an affliction that stifles the mental edge, critical thinking. And this the Army cannot afford.

Bibliography

- Bonaparte, Napoleon, Napoleon’s Art of War, Barnes & Noble Books, Barnes & Noble, Inc., New York, 1995. Translated from the French by Lieutenant General Sir G.C. D-Aguilar, C.B.

- Clausewitz, Carl von, On War, Penguin Books, Middlesex, England, 1968. On War or Vom Kriege was originally published in 1832.

- Howze, General Hamilton H., U.S. Army (Ret.), Army Aviation, Vol. 25, Nos. 8 & 9, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., August-September 1977.

Historical Perspective / By Mark Albertson: Editor’s Note: This is the first of two articles commemorating the 55th Anniversary of the Battle of Ia Drang, Vietnam

Helicopter of MAJ Bruce Crandall, commander of the 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion, low over LZ X-Ray.

Fifty-five years ago, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) went on the attack. Division commander, MG Harry W.O. Kinnard, ordered COL Thomas W. Brown, commander, 3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, to send units south of the Ia Drang River, within the shadow of the Chu Pong mountain range. Brown’s units were the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 7th Cavalry Regiment and 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment. To the east, some six or seven miles at LZ Falcon, two batteries of 105 mm howitzers would be set up for fire support. 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, commanded by LTC Harold G. Moore, was to be inserted by helicopter into LZ X-Ray, 1030 hours, November 14. Objective: Engage in search and destroy operations in the Ia Drang Valley.

The Initial Assault

1017 hours, artillery loudly opened the debate, bombarding Landing Zones X-Ray and Tango for eight minutes; followed by a twenty minute shelling of the former. Once lifted, UH-1B helicopters from the Aerial Rocket Artillery battalion continued the softening up process. The above remained on standby for continued support. Helicopter gunships escorted troop-carrying Hueys. The gunships lent suppressive fire with machine guns and rockets. Incoming lift copters saw their door gunners add to the suppressive fire as they landed Moore’s cavalrymen, with Company B making the initial assault.1

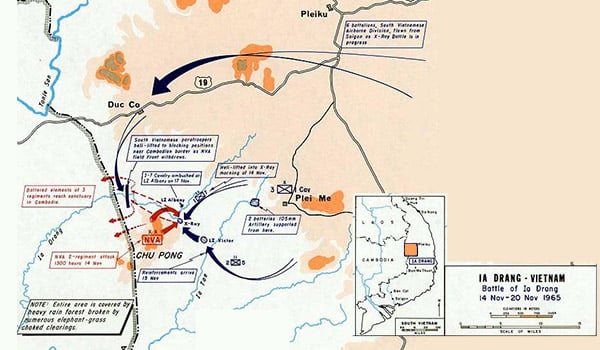

The battle of the Ia Drang, 14-20 November 1965; LZ-X-Ray in the center of the map./ U.S. ARMY GRAPHIC, WIKIPEDIA COMMONS

Sixteen helicopters inserted Bravo Company onto X-Ray. The clearing was expansive enough for 8 to 10 helicopters at a time. Turn-around time for helicopters to bring in A, C and D Companies had been planned for no more than thirty minutes.

“Once on the ground, Alpha and Bravo Companies were to assemble in attack formation just off the north and northeastern sectors of the landing zone, prepared to search east and northeast on order, with Alpha Company on the right. Designated first as a reserve force, Charlie Company would assume the security mission from Bravo Company on order, with a prepared task to move west and northwest, searching the lower portion of the Chu Pong, located just west of the landing zone. Bravo Company had priority of fire at the start, but once the westward push from the landing zone began, priority would shift to Alpha Company.”2

The Battle Develops

During the course of the battle, November 14 and 15, the UH-1 Huey helicopter proved invaluable. MAJ Crandell commanding the 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion lifted Moore’s cavalrymen into action. During the fourth round of landings, the NVA took X-Ray under fire, increasing the intensity as the Communists awoke to the danger. General Chu Huy Man attacked the cavalrymen from all sides, while raining 60 mm and 81 mm mortar rounds onto X-Ray. By 1330, Bravo Company was being heavily attacked by two NVA companies, supported by rocket and mortar fire; and its right platoon was in danger of being cut off.3

LTC Harold G. Moore, on his phone, during the battle of LZ X-Ray, November 14-15, 1965./ WIKIPEDIA COMMONS PHOTO

Alpha Company was ordered to protect the left flank of the heavily engaged Bravo Company; in addition to assisting Bravo to come to the relief of the beleaguered right platoon threatened with encirclement.4 Tube artillery and ARA began a pummeling of the Chu Pong foothills and enemy infiltration routes.5

Meanwhile, as Bravo Company was in a thick of a fight, Charlie Company was making its entry into a hot landing zone. “In fact, as the last elements of C Company landed, lead elements of D Company landed. “As they landed, the helicopters took numerous hits, but none were shot down.”6 However, “one radio operator was killed before he could dismount from a helicopter and the door gunner and pilot were wounded. “Colonel Moore stopped the other eight UH-1-Ds from landing. “Those who landed from D Company immediately became engaged in a fire fight near A Company. “The fighting became more intense. “Colonel Moore decided to pull back A and B Companies under cover of heavy supporting fire and smoke to the fringe of the landing zone and set up a tight defensive perimeter for the night.”7

Sustaining the Fight

MAJ Crandall asked for volunteers to fly in needed supplies, evacuate wounded and bring in reinforcements. “Tactical air flew missions throughout the night and the Air Force flare ship maintained constant illumination of the battle area. “Pilots of lift ships braved the dangers of the fire-swept L-Z to bring in reinforcements and re-supply and carry out wounded and dead.”8

As night fell, attempts to break through to the “lost platoon” had come up short, though communication was maintained. The NVA conducted probing attacks against Moore’s perimeter. Attacks against the isolated platoon, as well as X-Ray, were repulsed. Defense was bolstered by gun batteries at Falcon. More than 4,000 rounds of ordnance had been expended in close support.

To be continued.

ENDNOTES:

- See page 78, Chapter IV, “The First Airmobile Division and the Buildup, 1965: The Ia Drang,” Vietnam Studies: Air Mobility, 1961-1971, Lieutenant General John J. Tolson.

- See pages 7 and 8, “Ia Drang Valley Campaign Oct.-Nov.1965,” by MSG Erik Wilson, MSG Jeff Noe, MSG June Pugh, MSG James Wells and MSG Shannon Boyer.

- See page 26, “Battle of LZ X-Ray,” by Captain Robert H. Edwards.

- See page 5, “After Action Report, Ia Drang Valley Operation, 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, 14-15 November 1965,” Commanding Officer, 3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile).

- ibid page 6

- ibid page 7

- See page 78, Tolson.

- See page 141, “14 November, 1. Operations Summary, Operations Report, Lessons Learned, Report 3-66, The Pleiku Campaign.” The reference to MAJ Bruce Crandall asking for volunteers to maintain that lifeline of supply and reinforcements was in response to LTC Moore closing down the landing zone so as to prevent Army Aviators from incurring heavy losses which would threaten the continuing operation of the lifeline. This can be found on page 128, “Landing Zone (LZ) X-Ray –desperate times, conspicuous heroism,” A History of Army Aviation, by Dr. James W. Williams.

For greater detail on MAJ Crandall asking for volunteers to continue flying into LZ X-Ray, go to page 117, Chapter 9, “Brave Aviators,” We Were Soldiers Once . . . And Young, by LTG Harold G. Moore (Ret.) and Joseph L. Galloway. In addition, refer to pages 114 and 115, explaining how “slick crews,” those trained to fly in troops and supplies were also ferrying wounded. Transportation of wounded was the province of MEDEVAC; but, at this stage of the war, MEDEVAC commanders were denying their aviators and helicopters from landing in hot zones. Again, refer to Williams, page 128, as well with regards to commitment of MEDEVAC: “Casualties mounted quickly. The need for MEDEVAC was urgent, but the recent experience of losing these helicopters came into play. The unit called for MEDEVAC, but the new division policy for MEDEVAC required a cold LZ for five minutes. That was impossible. This left the lift unit to carry out wounded.”

Finally, we see Moore faced the prospect that without preserving Landing Zone X-Ray, he faced defeat.

Mark Albertson is the award-winning Army Aviation Publications Historian and a contributing editor to ARMY AVIATION magazine.

Guest Editorial, By General J.H. Binford Peay III, Commander-in-Chief, United States Central Command, MacDill Air Force Base, Florida. Edited by Mark Albertson.

* * * * *

General George S. Patton once declared that you should never attack where the enemy expects you to come. Attack weakness. Hold the enemy by the nose and kick him in the pants.[1]

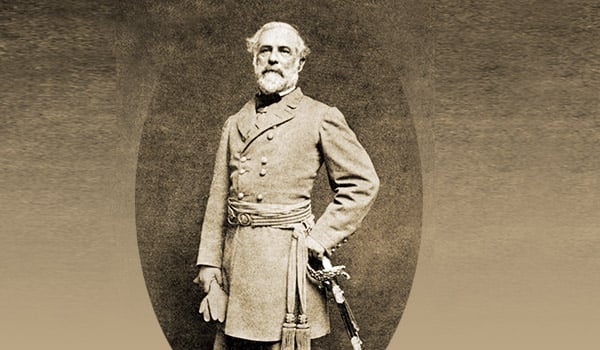

General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, engaged a Union Army superior in numbers, commanded by General Joseph Hooker. Lee audaciously divided his smaller army and with the use of the indirect approach, as alluded to by General Peay, defeated the Federals at the battle of Chancellorsville, May 1-6, 1863 / Wikipedia Commons/Heritage Auction Archives

In his own pithy way, Patton was recounting the much talked about coveted indirect approach in battle. Hannibal’s maneuver at Cannae, Napoleon’s triumph at Austerlitz. Lee’s surprise at Chancellorsville, MacArthur’s gamble at Inchon, and Schwarzkopf’s “hail Mary” offensive all reflected the Great Captain’s drive to gain military victory quickly, decisively, and at least cost by doing the unexpected. Advances in military technology during the last half century have raised this concept to new heights, accelerating changes in weaponry and doctrine that pose both opportunities and mindboggling challenges for the American military. Nowhere is this more evident than in the maturation of Army Aviation. We have seen it evolve from aerial observer for the artillery during World War II, air ambulance during the Korean War, and troop transporter in Vietnam to become a lethal weapon of maneuver and destruction during DESERT STORM. This transformation has not escaped the attention of the United States Central Command, where the capabilities of Army aviation are being embedded in operational plans.[2]

Such capabilities have become increasingly important as the U.S. armed forces redirect their energies away from the familiar Soviet dominated landscape of the Cold War toward the less well defined, multi-dimensional demands arising out of ubiquitous regional conflicts. The trend is particularly applicable to the Central Region, a complex collection of 19 nations that stretches from the Horn of Africa and Egypt through Jordan and the Gulf States to Afghanistan and Pakistan and which incorporates the waters of the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Gulf of Oman, and the Arabian Gulf.[3]

Maintaining security and stability in this part of the world is essential to the political and economic well-being of American and of the entire international community. Some 65 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves are buried beneath the wind-blown sands of the Gulf States—oil that provides the United States with 22 percent of its needs.[4] Western Europe 43 percent, and Japan 68 percent. Most of this oil must transit the narrow straits of Hormuz, as well as the Bab El Mandeb, and the Suez Canal—maritime choke points that can be easily blocked.

In addition to safeguarding the oil that fuels the global economy, the United States also focuses on defending freedom of navigation and access to markets, assuring the safety of U.S. citizens and property abroad, and promoting the security of friendly states within a comprehensive Middle East peace framework. Other interests include promoting respect for human rights and democratization, providing humanitarian assistance, and countering drug traffickers. We also seek to foster economic development, prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and defeat of international terrorism.[5]

* * * * *

Safeguarding these vital and enduring interests is a formidable task. USCENTCOM must undertake policies and operations in a diverse region, rich in culture, but plagued by endemic hostilities. The birthplace of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the Central Region is home to 427 million people from 17 different ethnic groups and 420 major tribal groupings.[6] Such multiculturalism is combined with border disputes, competition for resources, radical political and religious movements, economic strains, and exploding populations to provide fertile ground for both internal and external conflicts. Aggravating these sources of friction are Iraq and Iran, the gravest national threats to regional peace and stability. Both seek dominance in the Gulf and have frequently attempted to intimidate their weaker neighbors.

UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter / Army Aviation archive photo

After losing more than half of its conventional military strength in the Gulf War, Iraq is overcoming crippling international economic sanctions and intrusive United Nations inspections to maintain the largest collection of ground forces in the region. Furthermore, as it did during its invasion and subsequent occupation of Kuwait in 1990, Iraq repeatedly demonstrates the capability to mobilize rapidly and to move large troop formations quickly to threaten Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

While Iraq remains the near-term challenge, Iran is the long-term threat. Fifteen years after seizing power, Iran’s revolutionary regime continues its quest to dominate the Gulf and to become the spiritual leader of the Islamic world. With its vast oil reserves, many engineers and technicians, and large population, Iran has been able to overcome internal unrest and economic malaise to pursue its ambitions. It has purchased submarines, attack aircraft, and anti-ship missiles while underwriting Islamic extremists worldwide, militarizing disputed islands, in the Strait of Hormuz, and seeking to disrupt the peace process.

These threats are inflamed by the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Iraq and Iran have joined several other states worldwide trying to acquire ballistic and cruise missiles and chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. The difficulty of their quest is made easier by the willingness of nations such as Russia and other former Soviet republics, North Korea, and China to sell advanced weaponry to anyone with hard cash. This situation is made even more worrisome by the ease with which older systems can be improved through purchases of “off-the-shelf” technology. As potential foes procure and upgrade sophisticated systems and harden and conceal command and control, launch, research and development, and storage sites, our military forces will have increasingly greater difficulty finding and striking them when required.

* * * * *

In devising a military strategy and associated campaign plans to contend with these threats, USCENTCOM must compensate for lines of communication that stretch more than 7000 miles from the United States. Potential adversaries, on the other hand, need only travel 100-150 miles to reach Kuwait and the Saudi oil fields. This time-distance problem is further aggravated by the absence of formal agreements and alliances with local states, the need to balance military requirements with cultural sensitivities, and demands of having to fight, maintain, and communicate in some of the world’s harshest climates and most rugged terrain.

To meet these trials, we at USCENTCOM engage in activities that satisfy near-term requirements and offer the basis for confronting long-term threats. A major foundation for these efforts is the strong relations forged with our regional friends over the years. We have been able to address with them our mutual security concerns while also gaining access to the region. It is this access that secures our interest and provides the operational capabilities needed to deploy and employ our military force. From this base, we pursue an array of initiatives that support our peace and wartime goals. We maintain a relatively small but lethal mix of air, ground, and sea forces forward in the Gulf and reinforce these with additional units and individuals participating in robust exercise and security assistance programs. To reduce deployment time-lines, we preposition sizeable stockpiles of supplies and equipment ashore throughout the region alone and augment these with other stocks afloat. While critical, activities in the region alone do not meet our security needs. Success in future conflicts requires that we be able to project power rapidly from the U.S. and elsewhere in the world. To meet this need, we routinely practice speedy mobilization and deployment of trained and ready units, people, and equipment. Through the cumulative effect of these activities, we promote regional peace and stability, deter hostilities, limit the intensity of conflict should deterrence fail, and fight and win wars when required.

While we seek to employ these measures to deter conflict by convincing would-be aggressors of the futility of using force to achieve hostile aims, we recognize that our success requires being able to fight and win on the battlefield. In such circumstances, we expect U.S. forces operating in the complex strategic environment of the Central Region to be adept at waging high-intensity warfare with coalition partners. Units and leaders that can meet this operational challenge possess the flexibility and versatility to handle threats spanning the conflict continuum.

In this context, Army aviation offers incomparable qualities. Speed, firepower, precision, maneuverability, flexibility, mass, and surprise—around the clock and in adverse weather; these are its trademarks. Army Aviation introduces onto the battlefield new concepts and technology that allow us to realize the indirect approach in warfare on an unprecedented and massive scale.[7]

To underscore this last point, consider the dramatic maturation that we have experienced in vertical envelopment, a modern form of the indirect approach.

Back on June 6, 1944, American paratroopers of the 101st and 82nd Airborne divisions grimly prepared to jump or fly gliders into Nazi occupied France. Green lights went on as aircraft passed over what the pilots believed were the designated objectives.

Fog, flak, and imperfect navigation caused many of the aircraft to miss their designated drop zones. Gliders crashed far from their desired landing sites. Paratroopers landed in pastures, orchards, and towns. They drowned in canals and rivers.

Some came under a withering hail of bullets as they struck the ground. Others wandered aimlessly for hours looking for friend and avoiding foe.

General J.H. Binford Peay III / Wikipedia Commons

It took all night to assemble units. Throughout the early morning, small bands joined up and moved toward assault objectives. Those that did not land in their assigned drop zones carried out the missions assigned to whatever sector they found themselves in. This largest U.S. airborne assault up to this point in history shocked the Germans. It was audacious. It disrupted Nazi command and control. It obstructed the movement of enemy reserves and artillery. And it demoralized the German defenders.

At the same time, the airborne drops revealed grave shortcomings. While the dispersion of the paratroopers confounded enemy defenders, it undercut the concentration of the meager combat power of the American troops. Lacking firepower and ground mobility, the paratroopers were unable to reach many of their assault objectives. More vigorous Nazi counterattacks would have routed them. The operation was also costly. The 101st, for example, suffered 3,800 casualties, nearly one-third of its strength, by the end of June 1944.

Compare the D-Day airborne operations with the performances of all our aviation units—lift, reconnaissance, assault, attack, medical, and command and control—during Operation: DESERT STORM.

This was the realization of the dream of aerial envelopment, conceived by the World War II generation and nurtured by American warriors in the jungles of Vietnam.

Speed, mass, precision, and shock, which were unattainable with the dispersed airborne landings in Normandy, were achieved by leveraging the technological reliability and pinpoint accuracy of the Black Hawk, Chinook, Apache, Cobra, Iroquois, and Kiowa helicopters in some of the world’s harshest climates and most difficult terrain.

As we look to the future of war in the Central Region, we will build on our recent wartime experience. Capitalizing on advances in avionics, communications, computers, fire control and delivery systems, munitions, and mobility, we will be able to achieve an unprecedented fusion of intelligence, fires and maneuver.

Comanche, the centerpiece of the aviation modernization effort, will scout the battlefield round the clock and in all-weather, sharing information and imagery with other ground, air, sea and spaced-based sensors.

From these capabilities, friendly forces will share a remarkable extended view of the battlefield and possess the tactical means to reduce target acquisition and engagement times dramatically. Armed with these tools, senior commanders will exploit the lethal punch of the Longbow Apache and use of powerful fires from tactical aircraft, artillery, and ground maneuver forces to pummel the enemy across the width and depth of the theater operations at an extraordinary pace.

Simultaneously, UH-60 Black Hawks and CH-47 Chinooks or a follow-on heavy lift bird, will rapidly project infantry and artillery deep into the heart of the enemy, where they will block lines of communication and wreck reserves. Whatever can be seen will be immediately destroyed. These cascading, simultaneous, punishing attacks will lay waste to the enemy’s weapons and collapse his will to fight.

The depth and destructiveness of these vertical envelopes transcend the tactical level of war. Striking the enemy where he is most vulnerable and least prepared to respond is “operational level warfare.” Aviation technology offers the theater commander new opportunities: maneuver and firepower to cripple enemy strategic systems and sites, control operationally significant terrain, and destroy the enemy’s operational forces. So endowed, today’s senior commanders carry the key that unlocks the mystery of the indirect approach on a revolutionary scale that would be the envy of a Lee or MacArthur.

While technological breakthroughs in aviation are an essential part of this transformation in warfare, we must remember that operational success will continue to rest, as it always has, on the shoulders of our young leaders—leaders with highly honed tactical and technical skills; leaders cut from the same mold as Lee, Gavin, Ridgway, Taylor, Howze, Kinnard, . . . and other Army aviation and air assault visionaries. In the words of author Tom Wolfe, we will need aviators with the “Right Stuff.”

“The “Right Stuff.” One either has it or one doesn’t. It is a quality that combines speed of mind, dexterity, common sense, courage, physical and mental strength and determination. It involves the willingness to take risks and a yearning to be the best. Army Aviators brandish these rare traits every day as they take-off in a hurtling piece of metal comprised of imperfect mechanical components. They must contend with questionable weather, the trials of fatigue, and well-armed opponents. And they do this 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

As Tom Wolfe posits, those who pass this seemingly endless series of trials join the ranks of the splendid few at the top—the top “brotherhood and the Right Stuff.” We are fortunate that the ranks of Army aviation swell with men and women with the “Right Stuff”—soldiers endowed with the traits required to defend our nation and that announce to the world that America’s armed forces stand ready to do what must be done to win anywhere, today and tomorrow.

Source: See pages 8, 10, 34-36, “Triumphant Flight: Army Aviation in the Central Region,” Army Aviation, Vol. 45, No. 1, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport , Ct., January 31, 1996.

Endnotes

- General George S. Patton, Jr’s pronouncement is pure Sun Tzu:

Point 4: “When the enemy is at ease, be able to weary him; when well fed, to starve him; when at rest, to make him move.

Point 5: “Appear at places to which he must hasten; move swiftly when he does not expect you.

Point 15: “For if he prepares to the front his rear will be weak, and if to the rear, his front will be fragile. If he prepares to the left, his right will be vulnerable and if the right, there will be few on his left. And when he prepares everywhere he will be weak everywhere” See pages 96 and 98, Chapter VI, “Weaknesses and Strengths,” The Art of War, by Sun Tzu. Besides General George S. Patton, Jr., Mao Tse-Tung was heavily influenced, too, by Sun Tzu. Read On Guerrilla Warfare by Mao Tse-Tung. Editor’s note. - Looming in the background of any war being planned as a short, sharp conflict, are the words put forth again by Sun Tzu: “For there has never been a protracted war from which a country has benefited. Li Ch’uan: The Spring and Autumn Annals says: ‘War is like unto fire; those who will not put aside weapons are themselves consumed by them.’” See page 73, Chapter II, Point 7, The Art of War, by Sun Tzu. Editor’s note.

- The areas in question, as put forth by General Peay, are products, for the most, of the collapse of the dominance by 1945, by the once powerful White, Christian European colonial powers, which unleashed such forces as Revolutionary Nationalism. Editor’s note.

- In addition to the over-prepondering reality that oil is priced in Dollars, which is a large reason that the Dollar is the world’s reserve currency. The struggle, then, is every bit as much financial as it is material. Editor’s note.

- An ongoing and seemingly endless dilemma is, “about 250 million out of 400 million across 10 Arab countries, or two-thirds of the total population, were classified as poor or vulnerable.” The Middle East, then, is one of the most unequal in the world, leaving many families in poverty for generations. And with governments that cannot or will not provide basic services and economic opportunities, especially for the large younger segments across the Middle East demographic, many turn to the such actors as the Muslim Brotherhood and Hezbollah for assistance. See page 2, “How Poverty and Inequality Are Devastating the Middle East,” by Rami G. Khouri. Editor’s note.

- In an area with only one percent of the world’s fresh water, the precipitous rise in population growth, together with economic inequality and authoritarian regimes, virtually assures stormy waters ahead. For instance, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen, in 2018, were peopled by some 484 million souls; by 2030, 581 million and by 2050, 724 million (Source: UNICEF, 2018.). See page 2, “Middle East Demographics to 2030,” by Paul Rivlin.

- The Airmobility concept enabled conventional troops to operate as guerrillas; from the perspective of being able to strike an enemy’s rear and then quickly retire to another front; or, attack a flank to put an enemy force off balance, perhaps in preparation for a major attack or to cover the withdrawal of a main force. The battle of Ia Drang, November 1965, offers a case in point. Here elements of 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) were inserted by helicopter behind the enemy’s front. Control of the Third Dimension enabled the constant supply and support of the skycav units inserted into enemy-controlled territory. By comparison, guerrillas freely move by foot, for the most part. They strike and then withdraw. But many of their caches of supply and equipment are sedentary, therefore at risk of confiscation and/or destruction. For the skycav soldiers, their element of supply and mobility is mobile, and as long as control of the air is assured, movement and control of the battlefield is greatly enhanced.

Bibliography

- Khouri, Rami G., “How Poverty and Inequality Are Devastating the Middle East,” Carnegie Corp of New York, www.carnegie.org/topics/topics-article/why-mass. . .

- Peay, General J.H. Binford, “Triumphant Flight: Army Aviation in the Central Region,” Army Aviation, Vol. 45, No. 1, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., January 31, 1996.

- Rivlin, Paul, “Middle East Demographics to 2030,” The Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies, Tel Aviv University, August 21, 2019. Dayan.org/content/middle-east-demographics-2030

- Tzu Sun, The Art of War, Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford, 1963. Introduction by Samuel B. Griffith, with a Foreward penned by B.H. Liddell Hart. The Art of War was reputedly written by Sun Tzu some 2,500 years ago.

Army Aviators to Attend National War College

(All are Lieutenant Colonels, unless otherwise noted.)

Allen, James R.

Bunyard, Jerry M.

Chritton, William R.

Mullen, Jack L.

Robertson, Victor M.

Stevens, Story C. (P)

Wooley, Wilson C.

Army Aviators to Attend the Industrial College for the Armed Forces

(All are Lieutenant Colonels, unless otherwise noted.)

Descoteau, Rudolph

Islin, John A.

Morris, John J.

Rathbone, William A.

Sergeant, Wayne B. (P)

Teague, Jerry I. (P)

Toner, Francis J.

Source: Pages 11 and 12, Army Aviation, Vol. 19, No. 12, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., December 15, 1970.

The National Aeronautic Association announced, on 22 August 1996, that Jean Kaye Tinsley had been selected as an Elder Statesman of Aviation. Tinsley began her aviation career in San Francisco, California during the mid-1940s, and has served the industry in the capacity of Applications Engineer and as technical editor and writer on all types of manuals and for operation and maintenance overhaul and field instruction as well as many types of brochures. The FAA has designated her as a Written Test Examiner and an Accident Prevention Counselor. In 1965, she attended the annual convention of the “Whirley Girls” and then became Whirly Girl No. 118. Since that time, she has held several offices in the organization and is currently its Executive Director. Tinsley was co-founder of the Helicopter Club of America, its charter member No.1, and was its first president.

Source: “Briefings,” page 3, Army Aviation, Vol. 46, No. 1, Army Aviation Publications, Inc., Westport, Ct., January 31, 1997.

Historical Perspective / By Mark Albertson: Editor’s Note: This is the third and final article commemorating the 70th anniversary of the Korean War.

ALL PHOTOS AAPI FILE PHOTO

V-J-Day, September 2, 1945, the Air OPs boasted 2,630 pilots, 2,252 mechanics and 1,600 aircraft. Before the year was out, only 200 aircraft remained. The Air Observation Post was not only facing irrelevance, but outright extinction. Yet with the National Defense Act of 1947, the United States Army Air Forces became the United States Air Force. It was imperative, then, that the Ground Forces have a capability – no matter how rudimentary – for serving their immediate tactical air needs. And despite bumps on the road ahead, this would prove to be the launching pad for Army Aviation as we know it.