Looking Back / Army Aviation, February 2023; By Mark Albertson

Branchhood, By Mark Albertson

Part I: Technology, Command and Control

Army Aviation breaks friction with the ground, operates in the ground regime, and greatly enhances the capability of the force. . . [1]

*****

The remarkable evolution of aerial observation, together with the aerial direction of artillery fire within the United States Army, began with the War Between the States and a military application known to history as the Balloon Corps. The suitable starting date is June 18, 1861, when Thaddeus Lowe lifted off from the Columbia Armory[2] and from the balloon basket of Enterprise, Lowe’s telegrapher transmitted the first electronic message from an aircraft in the air to the ground. And one of the recipients was President Abraham Lincoln, marking the sixteenth president as the first head-of-state in history to receive an electronic message from an aircraft in the air to the ground.

Following America’s first industrialized conflict, the Army will again resort to the lighter-than-aircraft during the Spanish-American War. But with the maturation of aerial observation and reconnaissance, as well as the growing sophistication of the aerial direction of artillery fire, the appearance of fixed wing aircraft and the exciting promise of its mobility, consigned the gas bag to history. Then came the advent of the Air Observation Post, June 6, 1942, laying the groundwork for what would later become Army Aviation; to which the growing reliance on the helicopter during the Korean conflict, advanced this evolving medium of conveyance to becoming an absolute necessity in Vietnam . . . all showcasing, in a clear and unmistakable horizontal progression of history, the developing sophistication of this military exercise known as Army Aviation.

Indeed, Army Aviation is the product of American invention, innovation and the specialization of tasks; the result, too, of the Industrial Revolution which, together with Man’s penchant for technological innovation, we find Army Aviation is alive and well in the era of the Technology Revolution. A progression that has stimulated the specialization of tasks in the modern era.

L-4 Cub aboard and LST carrier during World War II. Top flight technology for the Air Observation Post.

The profession of arms, as is seen in many other professions in the American economy, society and culture, has, thus far, not proven itself immune to the globe-changing continuum known as the Technology Revolution. The profession of war, again like other professions, has become less labor-intensive. Gone, too, are the days when the backyard mechanic, able to repair his ’36 Ford, could easily perform in-theater servicing of a Piper L-4 Cub; a hallmark of the pre-Army Aviation era of the Air Observation Post of the Field Artillery.

On the heels of the 1914-1918 chapter of the Great War and the interregnum period that followed till the resumption of the global conflict, the evolving nature of the strategic bomber proceeded apace; as did the specialization of tasks concerning those airmen who flew, repaired and directed this increasingly sophisticated aspect of modern war. To the point that the science of airpower had become too sophisticated to be properly administered by officers specifically trained and educated to prosecute a ground war. Hence, in 1947, the United States Army Air Forces became the United States Air Force, consummating a divorce long sought by the proponents of strategic airpower.

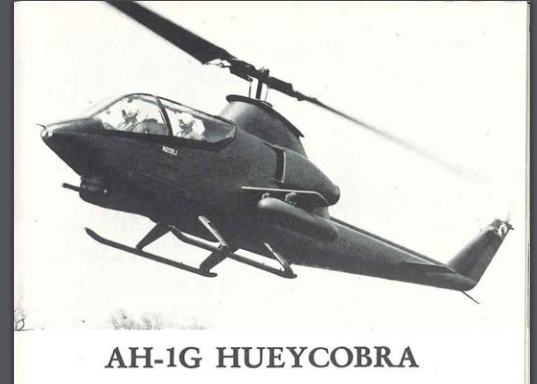

AH-1G Huey Cobra, providing Army Aviation the ability to provide support for the soldier on the ground.

Army Aviation, too, was not exempt from the natural laws of change. The Air Observation Post commanded by Colonel, then later General William Wallace Ford, minus the proponents of same, remaining oblivious to the strategic, tactical and material changes following 1945 and into the Korean War, set in motion a continuum that would culminate in branchhood by April 12, 1983. Take, for instance, a standalone issue such as technological changes. In less than ten years, compare the Sikorsky helicopter effort from the R-4 eggbeater to the H-19 Chickasaw used in Korea; to, in the following fifteen years, the Bell UH-1 Huey and later the Cobra attack helicopter in Vietnam; followed in the post-Vietnam era with the UH-60 Black Hawk and AH-64 Apache. Not many Black Hawk and Apache technicians were fixing their ’36 Fords in the family driveways.[3] The training and schooling today is beyond what was required to prepare the Class Before One. Such is Man’s tendency to improve, but which increases, many times, the sophistication of the task in question. Branchhood, then, was that result of a progression started on June 6, 1942 and, became more evident as the decades came and went. And so by the 1970s at the latest, the jury to some might have been out, but reality dictated a verdict that had already been delivered . . . it was just a matter of time, despite the pronouncements of naysayers, that branchhood was coming; verifying, indeed, that the progression of history is always fulfilled. . .

* * * * *

“. . . tools, or weapons, if only the right ones can be discovered, form ninety-nine percent of victory. . . . Strategy, command, leadership, courage, discipline, supply, organization, and all the moral and physical paraphernalia of war are as nothing to a high superiority of weapons—at most they go to form the one percent which makes the whole possible.”[4] There is certainly truth in what J.F.C. Fuller writes here. For instance, the technology or major tool for the existence and success for the Air Observation Post of the Field Artillery was the grasshopper-type aircraft. For Army Aviation it was the helicopter. This course was made easier when the Air Force, deciding to maintain strategic airpower in the nuclear era as its justification for existence, did not pay the proper regard for slow, rotary wing aircraft, since strategic airpower necessitated the constant improvement on aircraft for the implementation of that way of waging war: In other words, each new mark of aircraft had to fly faster, higher, haul greater payloads and be equipped with the latest technological marvels. In this, the argument can be made, that airmen are not specifically trained to wage ground warfare. Ground officers are trained to wage ground warfare, and enough of them understood the significance of the employment of the helicopter for superior battlefield mobility so as to be able to defeat an opposing host.

Endnotes

[1] See page 51, “Army Aviation in 1983-1992” The Modern Era Arrives,” Army Aviation, by Joseph Cribbins, December 31, 1992.

[2] Which today is the National Air and Space Museum.

[3] Used to be the simplicity of fixing your car was part of the attraction. For back in the day, you could open the hood and still see the street below. You could change the points and plugs and, grab hold of the oil filter, all without busting a knuckle, as well as removing the manifold of an engine block. Ever open the hood of your car today?

[4] See pages 65 and 66, Chapter 4, “Helicopter technology: Political Imperative or Opportunity?” The Army Gets an Air Force, by Frederic A. Bergerson.