Aviation Survivability / By CW3 Mark Chamberlin and Mr. Jeff Whitmire: Since World War I, military aviators have recognized the importance of collecting and analyzing battle damage in order to support aircraft upgrades, improve new aircraft design, and develop better survivability measures. During World War I, the role of aviation evolved from simple scouting to include more complex offensive operations. Scout planes, such as the French Blèriot XI, were gradually supplemented by planes designed to engage the enemy with direct fire, like the British Avro 504k. Both aircraft were quickly upgraded to improve their effectiveness. By collecting and analyzing battle damage data from each surface to air fire (SAFIRE) event, engineers were able to determined what improvements were needed in future aircraft designs. However, the engineers during World War I remained focused on upgrading existing aircraft to make them more effective in combat, not on designing future aircraft to make them more survivable for their crews.

Before World War II, however, engineers began to shift their focus more to the survivability of the aircrew. The design development of the B-24 and the B-17 bear this out. The B-24 incorporated a high-aspect Davis wing, which had low drag characteristics at a low angle of attack, giving it a bomb load, range, and cruising speed far superior to that of the B-17. However, the B-24’s airfoil was quickly degraded by any flak or cannon fire incurred from German fighters. The B-17, on the other hand, could withstand large amounts of battle damage, keep the crew safe, and continue flying, which earned it the nickname “The Flying Fortress.”

Before World War II, however, engineers began to shift their focus more to the survivability of the aircrew. The design development of the B-24 and the B-17 bear this out. The B-24 incorporated a high-aspect Davis wing, which had low drag characteristics at a low angle of attack, giving it a bomb load, range, and cruising speed far superior to that of the B-17. However, the B-24’s airfoil was quickly degraded by any flak or cannon fire incurred from German fighters. The B-17, on the other hand, could withstand large amounts of battle damage, keep the crew safe, and continue flying, which earned it the nickname “The Flying Fortress.”

Those data points collected on the more survivable B-17, like a larger wingspan, and pressurized cockpits for higher altitudes, went into the design of the B-29, “Superfortress,” which reached initial operating capability (IOC) in 1942 and saw utilization until its retirement in 1960.

British Avro 504K biplane

Nearly twenty years after the end of WWII, the first new fighter that incorporated survivability from its inception saw service in Vietnam. This new fighter, the F-4, was capable of taking large quantities of SAFIRE, and proved to be very survivable unless hit in a specific location. The F-4 had two independent primary sources of hydraulic power that converged at the dual tandem control surface actuators. A hit in the vicinity of any actuator powered by both primary sources could cause a total loss of hydraulic power at that actuator and possibly all actuators. When the hydraulic power to move the control surface was lost, the surface would usually go hard-over, resulting in an uncontrollable aircraft.

This type of vulnerability, where a single hit at a critical location on the aircraft can lead to an aircraft attrition kill, is known as a single-point kill. Consequently, this area was later armored, reducing the F-4’s vulnerability to SAFIRE and greatly increasing its survivability, an upgrade made possible by collection of battle damage.

In collecting and analyzing battle damage, determining the specific cause of damage to the aircraft is very important. For example the UH-1 helicopter that flew in Vietnam underwent several upgrades to make it more survivable against small arms fire. As a direct result of the battle damage data collected on UH-1s in Vietnam, the UH-60 design incorporated dual engines, redundant hydraulics and seats that compress for crew survivability making it one of the most survivable helicopters ever built.

Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress combat damage

BDC and ASE Development

Collection of battle damage not only contributes to upgrades and new aircraft designs, it has also become an integral part of developing ASE. Early in Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), a Tiger Team was assembled to determine the causes of individual SAFIRE events. Several aircraft were shot down by weapons systems which the Intelligence community assessed incorrectly based on human intelligence (HUMINT). The Tiger Team used battle damage data and forensic evidence, instead of HUMINT, to correctly assess the weapon system used in these shoot-downs. The Tiger Team’s assessment differed from the Intelligence community’s assessment. As a result, new aircraft survivability measures were adopted, which reduced the number of aircraft shot down. Today’s Joint Combat Assessment Team (JCAT) and the Army component to JCAT, the Aviation Survivability Development and Tactics (ASDAT) team, investigate and report on combat damage incidents to assess the threat environment for operational commanders and collect data to support aircraft survivability research and development. JCAT remained in the Area of Responsibility (AOR) collecting battle damage, while ASDAT deployed on catastrophic events. JCAT personnel continued their mission of collecting battle damage data, which often included forensic evidence, while continuously deployed to OIF/OEF for over a decade.

Responsibility for BDC

In November 2014 the Request for Forces (RFF) for support by JCAT expired. With JCAT no longer collecting battle damage data for deployed units, the task of collecting battle damage data now falls on the tactical operations (TACOPS) officers or the maintenance officers in Army Aviation units. The requirement for collection of combat damage is stated in AR 95-1, para 6-5, b. “Unit commanders will ensure damage to aircraft from weapons or weapons effects that is incurred during missions is recorded and submitted in accordance with this chapter.” The next update to AR 95-1 will delineate battle damage collection versus centralized battle damage assessments which are to be conducted by ASDAT or JCAT. When ASDAT or JCAT are not available, unit personnel will be required to collect damage data in accordance with published procedures. ASDAT is solely reliant on TACOPS and maintenance officers to collect combat damage for the future of military aircraft, unless the unit commander specifically requests ASDAT’s support.

AH-64 Apache combat damage, Operation Iraqi Freedom

Despite this reliance on TACOPS and maintenance officers, there is currently no battle damage collection training program for TACOPS officers. As an expedient remedy, ASDAT has integrated pre-deploying TACOPS officers into JCAT Phase One training at Fort Rucker, Alabama. However, the training goal for TACOPS officers is to learn how to collect battle damage data, while the goal of JCAT Phase One training is to prepare service members to become assessors. JCAT assessors receive Phase II and Phase III training in order to provide them the training and credentials to conduct battle damage assessments. Units that receive pre-deployment ASDAT briefings also receive a separate briefing that segregates the TACOPS officers specifically for training in the combat damage collection process.

The Way Forward

The way forward in the collection of combat damage for ASDAT consists of three different courses of action. First, ASDAT will continue to train the force on collection during pre-deployment training events. Second, ASDAT will present semi-annual or quarterly battle damage collection classes using the Aircraft Combat Forensic Lab at Ft. Rucker. Finally, ASDAT will work with the observer controllers (OCs) at the combat training centers (CTCs) in order to develop battle damage collection scenarios to reinforce the training TACOPS Officers receive on battle damage collection.

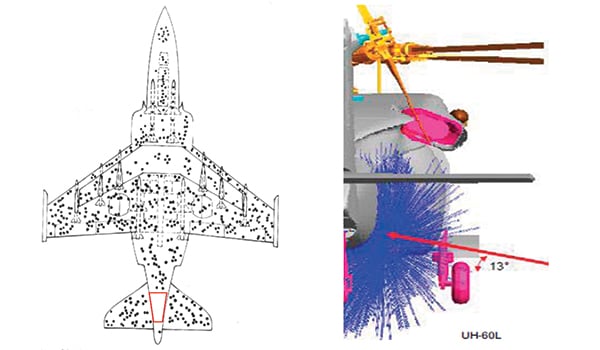

Diagram of an F-4 showing a single-point kill location on the aircraft (in red) which was identified by BDC and led to the area being armored, reducing the F-4’s vulnerability to surface to air fire (SAFIRE). RIght: UH-60 battle damage simulation

Simply collecting battle damage, however, does not provide engineers with the information they need to support aircraft upgrades, improve new aircraft design, and develop better survivability measures. Battle damage must be assessed, archived and analyzed, which is no simple task. For this reason, specialized teams exist to accomplish this task. These teams consist of personnel from the Joint Aircraft Survivability (JAS) program, ASDAT, JCAT, and the Defense Systems Information Analysis Center (DSIAC), who compile the data from every SAFIRE incident.

Their tool for archiving and analyzing battle damage data is the Combat Damage Incident Reporting System (CDIRS), which is available on a SIPRNet website. This information can then be scrutinized in order to support aircraft upgrades, as in the case of the F-4, improve new aircraft design, as in the case of the B-29 and UH-60, and to develop better survivability measures, as in the case of the Tiger Team in OIF.

Since World War I, military aviators have recognized the importance of collecting and analyzing battle damage data. Today, the tools have changed, aircraft are more complex, and engineers focus more on survivability, but the purpose of collecting battle damage data remains the same.

CW3 Mark Chamberlin is the CH-47 subject matter expert and Aviation Combat Forensics Officer and Mr. Jeff Whitmire is the intelligence specialist for the Aviation Survivability Development and Tactics Team, U.S. Army Aviation Center of Excellence at Fort Rucker, AL.