Story by Capt. Shervon Pope

FORT BRAGG, N.C. -The “All American” DUSTOFF company executes first in-flight whole blood transfusion over Fort Bragg Apr. 30.

Charlie Company of the 3-82 General Support Aviation Battalion (GSAB), 82nd Combat Aviation Brigade (CAB) is the first active Army unit to perform an in-flight prehospital blood transfusion outside a combat zone. Also known as the Fort Bragg “All American”, DUSTOFF Charlie Company conducts medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) operations year-round to support the installation and the surrounding area. DUSTOFF is an acronym that stands for Dedicated Unhesitating Service to Our Fighting Troops and is synonymous with life-saving aeromedical evacuations.

Since the activation of the installation’s whole blood program, flight medics have been authorized to transport blood and administer transfusions during aeromedical evacuations, which significantly improves patient survivability during prehospital transport. While whole blood transfusions are commonly performed in combat zones, this is the first of its kind.

On the afternoon of April 30, 2025, the company’s operation cell received an urgent 9-line MEDEVAC request containing limited information: a critical condition patient in the vicinity of Mott Lake, N.C.

“When a 9-line drops, that becomes our number one priority”, stated Chief Warrant Officer 3 Duro, pilot-in-command. After receiving the MEDEVAC request, the crew, which included Chief Warrant Officer 3 Duro, Chief Warrant Officer 1 King, Staff Sgt. Beighley, and Cpl. Sullivan, took action.

Beighley, the flight medic, prepared vital medical supplies. With nearly eleven years of training and experience, she learned to anticipate patient needs, including in-flight blood transfusions, now possible through the whole blood program activation. Sullivan, crew chief, and King, junior pilot, readied the aircraft with pre-flight procedures and safety checks while Duro determined the flight route. With limited information and mission urgency, Duro determined that securing a suitable landing zone (LZ) required intervention from Fort Bragg military police to manage ground traffic. The crew coordinated airspace with Simmon air traffic controllers and prepared with the Womack Army Medical Center (WOMACK) providers to expedite services upon arrival.

Within minutes of the MEDEVAC request, the duty crew hurried across the hangar at Simmons Army Airfield and took flight toward Mott Lake. Although each crew member had their own unique experiences, they all shared one commonality: this mission signified their first point of injury (POI) at Fort Bragg. It would also be the first time a medical evacuation included in-flight transportation and transfusion of whole blood above a military installation.

“This was my first call here and out of training as a sole provider,” said Beighley, “I was able to react accordingly and make the right decisions because I knew that I had a solid crew with me that day.”

Upon arrival, the duty crew quickly made judgments and coordinated with on-scene agencies, resulting in a safe aircraft landing. After receiving the Fort Bragg Emergency Medical Services (EMS) patient care report along with the patient, Beighley assessed

that the patient required blood authorized from the whole blood program. During the transport, she had only minutes to provide critical medical interventions to improve the patient’s outcome. Among them, Beighley executed the blood transfusion. The patient was successfully transferred to the Womack Army Medical Center for higher-level medical treatment.

King stated this MEDEVAC mission stood out among others because of intricate coordination with emergency services, supporting agencies, and crew synchronization, particularly between the flight medic and crew chief, which is essential to executing a successful

operation.

“In situations such as that call, we don’t have to ask questions. Everyone is prepared and knows what their role is,” said Sullivan.

Collaboration among the Womack Army Medical Center, Fort Bragg Range Operations Center, Fort Bragg Fire and Emergency Services, military police and Charlie Company are critical to medical evacuation success. The All American DUSTOFF is committed to enhancing patient care standards during aeromedical evacuations by consistently achieving new performance milestones.

Story by Maj. Jeffrey Windmueller

Chief Warrant Officer 4 Nicholas Demas was admiring the jagged peaks of the Swiss Alps cutting through the clouds when the radio crackled to life.

“Be advised, you are going to be intercepted by a Swiss fighter jet for training purposes,” the voice said.

Seconds later, an American-made F/A-18 Hornet appeared just 10 feet off his wingtip. Demas and his co-pilot snapped a quick photo, but the moment served as a stark reminder: this was no sightseeing trip. As an Army Reserve aviator, Demas was on a mission—flying halfway around the world to support Exercise Balikatan 2025, the 40th iteration of the joint and combined U.S.-Philippine military exercise in the South Pacific.

In doing so, Demas accomplished a rare feat: circumnavigating the globe in a twin-turboprop aircraft, the C-12 Huron.

. . .

Today, global travel is common. But circumnavigating the Earth in a military turboprop aircraft still requires meticulous planning and tremendous skill.

“Fuel management is one of the biggest concerns,” Demas said. “If weather happens, where can I go, and what can I do?”

Flying stateside, a storm over Dallas might just mean diverting to Oklahoma City. But overseas, in unfamiliar airspace, with limited fuel and no backup airfields, every leg had to be planned with precision.

Five months before takeoff, Demas and fellow pilots from Charlie Company, 6-52nd Theater Aviation Battalion began building the plan. The environment, extreme distances, and diplomatic hurdles of flying a military aircraft through foreign airspace demanded careful consideration.

“Part of my planning for this whole trip is APACS clearances,” Demas explained, referencing the DoD’s Aircraft and Personnel Automated Clearance System. “Every country’s approval includes specific airports. Landing at a non-approved location could cause serious issues.”

Based on the Beechcraft Super King Air 200, the Army’s C-12 is primarily used to transport distinguished visitors (DVs). With internal fuel tanks installed for the trip, Demas’s aircraft could stay airborne for over six hours at a time—closer to eight with careful fuel management.

Each landing was calculated to ensure at least 800–1,000 pounds of fuel remained, in case the aircraft needed to circle or divert due to emergencies or unfriendly airspace. These limitations, both mechanical and diplomatic, made one thing clear: the flight needed to continue eastward the entire way.

“We wouldn’t have had the fuel to fly westward, against the winds, to Alaska and then Japan,” said Chief Warrant Officer 4 Brittney Hobt, who joined the mission in the Philippines. “You’d end up making an unscheduled stop in the ocean.”

That added fuel capacity proved vital more than once.

Approaching Phuket, Thailand, Demas and Chief Warrant Officer 4 John Kittinger encountered a lightning storm so intense it seemed unreal.

“It was the craziest lightning storm I had ever seen,” Demas said.

Placed into a holding pattern at 15,000 feet, the crew watched as international airliners queued up behind them.

“We were the paper airplane in the sky, trying to land between these major airlines,” he said. When one jet was told it was “No. 20” in line, Demas knew he had to act quickly and precisely.

By then, Demas had logged 44 flight hours across 11 time zones—and was still days away from his exercise destination.

. . .

At Balikatan 2025, Army Reserve aviators flew across the Philippines supporting joint operations with the Philippine military and other partner nations, including Japan and Australia.

Operating the nimble C-12 allowed the Army Reserve team to move personnel and senior leaders across the islands, freeing up larger aircraft for logistics and combat support missions.

“They were standard missions, for the most part,” said Chief Warrant Officer 3 Donny Distler, who joined Demas in the Philippines. “But the collaboration between the four branches—it was seamless. It felt like we’d worked together for years.”

Still, there were challenges. In a non-FAA environment, navigating language barriers, different air traffic control procedures, and weather made each flight a test of skill.

“ATC was like the Wild West,” Distler said.

Controllers sometimes asked unexpected questions like, “Who are you and what’s your intention?”—prompting a moment of confusion before Demas answered: “To land?”

The runways themselves often added to the difficulty. Narrow, unlit strips—with tailwinds and monsoon rains—meant visual perception was easily distorted.

The aviators also supported training scenarios beyond transport.

In one exercise, Demas, Hobt, and Kittinger played roles in a simulated cockpit emergency, helping test and train local first responders.

“There were (simulated) smoke and fumes in the cockpit,” Demas said. “That triggered the emergency crews.”

While Hobt was treated for smoke inhalation and Kittinger for a simulated heart attack, Demas played a disoriented senior leader.

“I was told to be confused, concerned, and unaware of what was going on,” he said. “They had to control me and guide me to safety.”

. . .

When Balikatan concluded, Demas and Chief Warrant Officer 3 Ryan Rennecker launched from Misawa, Japan, into complete darkness—no stars, no visible clouds. Just the black of the sky above the Pacific.

Three hours later, the sun rose over the Aleutians, eventually giving light to steam rising from an active volcano on Great Sitkin Island.

“It was the most spectacular sunrise I’ve ever seen,” Demas said. “You could still see the stars behind you, but ahead, this bright edge of sunlight was cutting across the sky.”

After nearly 25 years in uniform, Demas knew this would likely be his final long-range mission.

From the deserts of Qatar to the atolls of the Maldives, from snowdrifts in Canada to the extreme heat of the Philippines, the globe-spanning mission tested every skill he had. Mechanical delays, diplomatic clearance hiccups, and weather all added to the challenge. But the payoff was returning home—over Memorial Day weekend—just in time to see his daughter’s softball game.

“All told, I flew more than 20,000 miles and 90 hours,” Demas said. “I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity.

“To a certain extent, I just flew my mission—but when I step back and realize I flew around the world in a twin-engine turboprop… it’s insane.”

OINT BASE LANGLEY-EUSTIS, Va. — Imagine a future where a UH-60 Blackhawk helicopter pilot, mid-flight, loses consciousness, and an onboard automated system reads the pilot’s vitals and autonomously flies the aircraft back safely, even alerting a medical crew to be at the airfield ready to treat the incapacitated pilot.

A groundbreaking fusion joining autonomous flight and operational monitoring of pilots’ vital signs just made that future possibility a present-day reality recently at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Virginia.

“This is the first time we have integrated the pilot’s health status to an autonomous flight control system,” said Carl Ott, a U.S. Army experimental test pilot with the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Aviation & Missile Center Technology Development Directorate.

Ott successfully flew this scenario together with co-test pilot U.S. Army Lt. Col. Greg Sievers, rotorcraft in-flight lab branch chief, James Carr, flight test engineer, and a team monitoring the mobile laboratory from the ground, integrating mission adaptive autonomy, and operator state maintaining, or OSM.

“This demonstration added in the capability of the OSM, so now if I have a pilot managing the system, he is flying, and all of a sudden gets incapacitated, he can [return to base], essentially going back to the point of origin,” Ott said.

JOINT BASE LANGLEY-EUSTIS, Virginia – Harrison Whittels, CEO of Tiger Tech Solutions, fits an Operator State Monitoring Technology band on the arm of U.S. Army Development Command test pilot U.S. Army Lt. Col. Greg Sievers, rotorcraft in-flight lab branch chief, Joint Base Langley Eustis, Virginia, May 1, 2025. The OSM is a biomedical sensor that monitors the pilot’s physiology during a flight. (U.S. Air Force photo by Crista Mary Mack)

While the aircraft was operating, data and video from the pilot and the helicopter were live streamed and monitored in real time. Mission adaptive technology is the term used to describe the autonomous flight capabilities, and OSM manifests itself as an arm band that monitors vital signs of the pilot similarly to an EKG machine.

“Our goal is to provide a tool to save the pilot, the crew and anyone on board, whether helicopter or another aircraft. If we can prove that concept, then everyone and everything can come home,” said Harrison Whittels, CEO of Tiger Tech Solutions, the company providing the OSM technology for the experiment. Whittels and his team monitored as the integration of all the systems were tested.

The flight was the product of a cooperative research agreement with the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Lab and Tiger Tech. While autonomous flight is something that is being tested already, this specific capability test is connecting the health and well-being of the pilots to an aircraft’s autopilot functions.

“This goes beyond flight stabilization, altitude and heading control,” said U.S. Army Col. Justin Highley, commander, DEVCOM Aviation & Missile Center Technology Development Directorate at Fort Eustis. “This technology has the further capability of connecting the status of the human flying the aircraft with the autopilot functions.”

JOINT BASE LANGLEY-EUSTIS, Virginia – “You see this little green blob? This makes me really happy,” Rick Whittington, Chief Operations Officer, Tiger Tech Solutions, said. Whittington explained that the little green on the screen he pointed to shows the current physiological condition of the helicopter pilot who being monitored mid-flight, and that it represents the state of the pilot being monitored, despite also being mid-flight, in real time, during the in-air test of combining monitoring the pilot’s vital signs via operator state monitoring and connecting that status to autonomous flight, called Mission Adaptive Autonomy. The experiment was conducted by a combined effort including U.S. Army Technology Development Directorate and U.S. Army Aeromedical Command. (U.S. Air Force photo by Crista Mary Mack)

The directorate Highley commands develops and demonstrates new technologies for aviation.

“We have a flying laboratory, which is only flown by test pilots such as Carl (Ott), specific for experimental test pilots for research type systems, used as a learning system, where we try in a flight environment different capabilities with the autonomy,” said Highley.

DEVCOM AvMC is the Army’s primary center for developing, integrating, demonstrating and sustaining Army aviation and missile systems. DEVCOM AvMC is a part of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, a major subordinate command of the U.S. Army Futures Command.

“What we are doing here is finding ways to cope with adaptive behaviors in the cockpits and aircraft that allows them to reduce the cognitive workload on pilots,” Highley said.

“Within DEVCOM AvMC we are working on how to add autonomy to the aircraft for high risk and really dangerous missions; we are particularly looking for ways to take our conventional aircraft and make them optionally manned,” Highley said. “For really dangerous operations, if we want to pull the pilots out and let the aircraft go by itself for a mission, we need to be able to provide that option to commanders.”

Highley added, that the technology of fully automated flights is still several years away. “You can never replace a pilot,” he said. “But now we have new ways to save a pilot.”

JOINT BASE LANGLEY-EUSTIS, Virginia – A different kind of Sikorsky UH-60 Blackhawk, the aircraft in this picture also flies autonomously and is used by U.S. Army test pilots for the U.S. Army’s Development Command Aviation Missile Center Technology Development Directorate at Fort Eustis. The autonomous flight capabilities, called Mission Adaptive Autonomy, are tested with other capabilities. “We have a flying laboratory, which is only flown by test pilots, specific for experimental tests for research type systems, used as a learning system, where we try in a flight environment different capabilities with the autonomy,” said Highley. (U.S. Air Force photo by Crista Mary Mack)

“We have some accidents in aviation, that a combat system can come in and warn the pilot it can save lives,” Highley continued. “All the modern cars nowadays have lane stabilization, so if you get too far out of the lane it shakes to let you know. We can do similar, where if it gets too far out in the danger zone or too far off your route, it can cue the pilot, have it shake the stick.”

The combination of the OSM with the autonomous flight also opens doors for additional possibilities, according to Ott. “Partnering with aeromedical research for this operator state monitoring, in addition to sending information itself, the OSM could also transmit to an aid station on the ground and there could be a medical response waiting for them, another possibility to broaden this capability,” he said. “We try to answer how to use technology to our advantage. The demonstration was small in scope but great in what the capability could look like on the future battlefield integrated with human users.”

OSM has been also recently tested in various capacities, to include monitoring Soldiers jumping out of airplanes, divers, and now with pilots.

“The future is this will be in common aircraft,” said Rick Whittington, chief operations officer, Tiger Tech Solutions. “If you can monitor your pilots, imagine how much it will assist air traffic controllers, how many lives it can save.”

Army Warrant Officer Meghan Polis, a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter pilot in the New York National Guard, doesn’t remember it but she logged her first three hours of helicopter flight time when she was just 3 months old.

Her father — New York Army National Guard Chief Warrant Officer 3 Stephen Polis — and her mother were going to a barbecue in Albany. They lived on Long Island and they decided to make the trip north by air instead of driving.

The flight school Stephen Polis worked for at the time as an instructor pilot allowed him to borrow a two-seat helicopter for the day. His wife held little Meghan to her chest and put cotton balls in the baby’s ears. And away the family went.

Sharing a Love of Flying

Since then, dad and daughter, both from East Patchogue, New York, have shared a love of flying that extends into their military careers.

On July 22, the two Army Guard aviators made their first flight together as pilots, during the 42nd Aviation Brigade’s annual training here.

The two are UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter pilots assigned to Company B, 3rd Battalion, 142nd Assault Helicopter Battalion, headquartered in Ronkonkoma, New York. They flew as pilot in command — dad — and pilot — daughter — on a morale flight for the mechanics, fuelers, supply people and other support personnel who keep the pilots of the 3-142nd in the air.

The aircraft, Stephen said, was the same one he flew in 2008-2009 when the unit deployed to Iraq.

Joining the National Guard

Stephen joined the National Guard in 1980 and started out as a mechanic and then became a crew chief. But, his intent was to become a pilot, and he did just that when he went to flight school four years later. From there, he conducted test flights as a maintenance test pilot before moving into air assault and medical evacuation missions.

“It took me a little while to prove my grit, so to speak, and to actually be accepted to flight school,” he said. “But I finally made it.”

Meghan followed in her father’s footsteps — as well as those of her grandfather, who was also a warrant officer — and took the same route as her father when she enlisted in 2013 and served initially as a mechanic.

After a couple of years, she submitted her packet for flight school and completed the training at Fort Rucker, Alabama, in February.

‘Family Tradition’

“It’s just kind of been a part of the family and I always felt like I could be a part of it,” she said. “By the time I came around to making the decision to do it myself, the little bit of aviation background I had was exactly the route I wanted to go.”

When his daughter graduated from flight school this year, Stephen pinned aviator wings on her on the same stage on which his father pinned his wings on him many years ago.

“A lot of family tradition is being created here,” Stephen said. “It was pretty prideful. Very rewarding.”

The July 22 flight started out slow and steady, as the pilots allowed their passengers to get a taste of aviation on the trip around the base. But halfway through the trip, with father and daughter each taking a turn at the controls, the pilots turned the action up a few levels with some dramatic banks, turns, dives and climbs over the wooded area. The maneuvers displayed the capabilities of the Black Hawk for the soldiers who spend their careers ensuring those helicopters have all the support needed for missions.

After the flight, Stephen complimented his daughter on her ability behind the controls, saying that she did a good job and made him proud.

Father ‘Had a Cool Job’

“I always thought my dad had a cool job. And now that I’m doing it, I know he had a cool job,” Meghan said. “It’s actually more than I expected. It’s so much more rewarding to be able to go out and be the one at the controls flying the aircraft and making decisions.”

Perhaps intentionally, Meghan used a pun to describe the experience of working alongside her father, saying she was “still kind of flying” after thinking about it for a while. When she initially wanted to learn to fly an airplane, she said her father refused to fly with her as a civilian instructor pilot.

“This time he didn’t really have a choice,” she said. “It’s really cool to actually be able to sit in the seat next to him. I’ve always kind of felt like I really wanted him to know how I fly, and now I guess he’s got an assessment and it’s not that bad.”

As a civilian pilot, Stephen said he has flown corporate jets around the world and logged more than 10,000 hours in jets and 10,000 hours in helicopters. In fact, he said, he stopped counting when he reached that threshold five years ago.

‘I’m Constantly Learning Things’

The love of flying is something he developed at a young age, and while many people dream of flying but never get the opportunity, he was fortunate enough to turn his love into a career.

“Aviation’s been very good to me,” Stephen said. “I have a smile on my face every day and every time I fly. It’s an itch that you try to satisfy.”

And after inheriting her father’s love of flying and also getting to turn it into a career, Meghan said it is amazing and “more than I thought it would be.”

She added, “I’m constantly learning things. Every time I fly with someone, they have a different technique. I’m really developing my own pilotage, my own techniques. It’s a challenge and it’s a thrill.”

Story by Sgt. Jonathan Monfiletto, New York National Guard

Story by Master Sgt. Arthur Wright

ELKINS, West Virginia — To ensure an understanding of Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO) and increasingly contested battlespace by adversaries, the District of Columbia National Guard led over 20 air and ground units across the U.S. Army and Air Force for exercise “Misty Dawn” in Elkins, West Virginia, between March 4-14, 2025. The joint readiness exercise highlighted coalition interoperability and high-end integrated tactics.

“Misty Dawn is an apex example of grassroots, unit-led, readiness and lethality innovation – Right Now! When leadership tells units to get after readiness, move faster, and increase lethality; Misty Dawn is one of our answers,” said U.S. Air Force Col. Clifford Taylor, Commander, 113th Wing Operations Group. “The intent is to allow participants to build proficiency in large scale operations. Misty Dawn creatively builds capability and capacity in non-traditional ways to bring weapons effects to bear on the enemy.”

West Virginia’s natural and mountainous setting provided key training benefits. The topography challenged ground and air participants to learn how to use terrain to their advantage. The West Virginia Department of Natural Resources and West Virginia State Parks facilitated the planning processes and training operations.

“There are few places in the country that provide such an tactically valuable training venue,” Col. Taylor said. “We are grateful for the collaboration with the West Virginia National Guard, West Virginia State Parks, and the West Virginia Department of Natural Resources that enabled the exercise to be hosted in West Virginia’s spectacular natural setting.”

The exercise also integrated airpower with ground force movements. Members of the D.C. Army National Guard’s 1-224th Aviation Regiment, also known as “Capital MEDEVAC” worked closely with West Virginia Air National Guard, Joint Terminal Attack Controllers (JTACs) from the 7th Air Support Operations Squadron and NATO partners from Germany and Slovenia.

“We were responsible for identifying a dislocated Air Force squad and effectively recovering them from hostile territory,” said CW2 John Nowadly, UH-60 Black Hawk pilot for the D.C. National Guard. “We tested our flying skills, flight medic skills, mission planning — that’s a huge component of this, and it also helps us cross-train with other services to ensure regardless of branch of service that the mission timelines are in sync.”

The strength of communications and coordination between Army ground forces and Air Force combat assets is essential. Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC) or Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) members serve as close air support experts, advising commanders on the use of Air Force assets in combat. The exercise added electronic warfare elements to simulate features of the modern battlefield.

“This exercise had some personnel who were working together for the first time,” said CW3 William Ralston, UH-60 Black Hawk pilot in command. “This tests our proficiency, coordination, and the ability for every section to do their part.”

Misty Dawn bolstered airspace and security operations. The exercise matched threats to capabilities and further prepares and modernizes the joint force’s ability to deter enemies who threaten our homeland, our partners and allies.

Story by Capt. David Block

WHEELER ARMY AIRFIELD, Hawaii – Soldiers, families and friends gathered to witness the ceremonial passing of the battalion colors as Lt. Col. Andrew S. Howell assumed command of 3rd Battalion, 25th Aviation Regiment, 25th Combat Aviation Brigade, during a change of command ceremony held recently on Wheeler Army Airfield.

Lt. Col. Samuel J. Diehl relinquished command after leading the Hammerheads through a period marked by high operational tempo, strategic innovation, and vital aviation support missions across the Pacific.

Col. Matthew J. Scher, commander of the 25th Combat Aviation Brigade, praised Diehl’s leadership and the Hammerheads’ enduring commitment to excellence in supporting operations both at home and abroad.

“According to Webster’s Dictionary,” Scher joked during his remarks, “‘Hammerheading’ — to Hammerhead — is to do everything. And to do most of it really well. Some things, just okay, like submitting SITREPs on time or writing short SITREPs. But the most important stuff — you do really, really, really well, with precision, and always the right way, and safely.”

Scher highlighted the Hammerheads’ lifesaving medevac support, jungle hoists, joint-force mobility missions across the Hawaiian Islands and the Luzon Strait, as well as their role in transporting senior leaders and fighting wildfires throughout the region.

He also thanked the families of both leaders, recognizing their often-unseen sacrifices.

“We are so grateful for the support of Sam’s family — Alison, Rowan, Mikey and Sarah — as well as Andy’s family — Hayden and Charlie here in the audience, and Elizabeth and Daniel who could not be here today,” Scher said. “Thank you for your sacrifice — in time, in special moments, in predictability.”

Lt. Col. Howell returns to the 25th Combat Aviation Brigade with deep ties and appreciation for the unit’s culture and legacy.

“I can’t tell you how excited Hayden and I are to be back home in the 25th CAB,” Howell said. “I am truly humbled by the opportunity to continue to serve and lead the finest men and women this country has to offer.”

Howell expressed gratitude to Scher for years of mentorship and to Diehl for his guidance during the transition.

“Sam, thank you for welcoming me into the battalion with open arms and for the mentorship you have given me through the process. I truly have some big shoes to fill,” Howell said. “The thing that has stuck out the most during my integration has been the phenomenal culture you have created within the Hammerheads.”

During his farewell remarks, Diehl offered heartfelt thanks to the formation and brigade leadership.

“Lots of people use their change of command speech to say they couldn’t have asked for a better boss, and we know they don’t mean it…but I mean it,” Diehl said. “Thank you for trusting me to lead, for entertaining my candor in the interest of shared understanding, for providing space for my leaders to learn and make honest mistakes, and for supporting the aspirations and goals of Hammerhead leaders. I can say confidently that your impact has been felt at echelon.”

He also gave a special shout-out to Task Force Hammerhead personnel forward deployed at the time of the ceremony.

“To Task Force Hammerhead forward — who I hope are not watching this ceremony — I could not be more proud of what you’ve accomplished in support of the division and joint force over the last four months,” Diehl said. “You enabled a joint task force to see, move, strike, and extend across strategically decisive terrain in the Luzon Strait.”

As the battalion begins a new chapter under Howell’s leadership, the legacy of mission excellence and esprit de corps established under Diehl will continue to shape the Hammerheads’ path forward.

Story by 1st Lt. Courtney Huhta

FORT CAMPBELL, Ky. — What began as a proud moment quickly turned into a career-defining milestone on stage for Sgt. Ronald Roberts after being named the AAAA Gary G. Wetzel Army Aviation Soldier of the Year at the 2025 Army Aviation Association of America Summit in Nashville, Tennessee. Roberts was preparing to return to his seat as followed by other recipients after delivering his acceptance speech—but instead, his wife was invited on stage.

Maj Gen. Gill, Commanding General of the Aviation Center of Excellence and Fort Novosel, took to the podium and pulled out a Sergeant E-5 rank. After recalling a conversation between the two from dinner the night before, Gill surprised Roberts with an on-the-spot promotion. Robert’s wife Kaitlyn, proudly pinned on the newly earned rank alongside Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, Gen. James Mingus.

“Getting promoted on stage was such an honor by such high leadership,” said Roberts. “I’ve worked hard to prove myself and show how much impact I can have—not just for my Soldiers but also for the Army.”

Roberts, a fourth-generation service member, enlisted in July 2021 as a 15R AH-64 Apache Helicopter Repairer, determined to uphold his family’s legacy while forging a path of his own. Since then, he has embarked on a journey across the globe traveling from South Korea to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he now serves with Bravo Company, 96th Aviation Support Battalion (ASB), 101st Combat Aviation Brigade.

Roberts was nominated for the honor by his section leadership in Bravo Company 96th ASB.

“I like the ASB lifestyle,” he explained. “It’s very family oriented. With the 96th, we’re trusted to manage our own time to get the maintenance done right and done on time.”

Since joining the ASB in 2023, Roberts has thrived under leadership that pushed him and his peers to rise. “Our entire section is promotable right now. I think that says a lot about the culture here,” he said.

During the summit, Roberts toured aircraft exhibits, networked with Army aviation leaders, and absorbed advice from generals and industry executives alike including a dinner with Jeffrey Schloesser, Executive Vice President of Strategic Pursuits of Bell Textron.

For Roberts, leadership is more than just a title, it is a responsibility.

“I’ve worked hard not just to prove myself, but to show what I can do for other Soldiers,” he said.

Today, he leads his section, guiding junior Soldiers with the same care he received as a new Soldier. Treating his Soldiers like family is a characteristic he uses to mentor and develop his peers.

Reflecting on his journey to this point, Roberts encourages others to seek new experiences and show up—even when recognition doesn’t feel guaranteed.

“Even if you’re not receiving an award, I highly recommend attending the summit,” he said. “You get to talk with leadership, hear their stories, and find out what’s possible in your own career.”

From fixing aircraft in the hangar to the national stage, SGT Ronald Roberts carries a new rank—and the respect of an entire branch—into the next chapter of his Army story.

I am honored and humbled to have been elected as your new AAAA National President a few weeks ago at our annual Mission Solutions Summit in Nashville. I know many of you from my long Army career and even more during the past six years as the AAAA Secretary, Treasurer and Senior VP. I look forward to meeting many more of you among our military, industry, and civilian members over the next few years.

I would like to thank our outgoing President, and my friend, MG (Ret.) Walt Davis, who led AAAA during the last two years and established such a cohesive team of your National Executive Group (NEG), including BG (Ret.) Tim Edens, now our Senior VP, and MG Todd Royar, our new Treasurer. It has been an honor to serve with and for Walt. I pledge to build on his many successes and work every day to represent you all, as we work through these times of change and challenge.

If my years in uniform taught me anything, it is that change is inevitable, and that Army Aviation and our Nation always come out better, stronger and more capable in the process. All of us at AAAA are flexing to better serve you in all of our four pillars of Networking, Recognition, Voice and Support as we embrace unmanned systems, autonomy, counter drone and all the realities of the emerging battlefield as we prepare for future conflict.

Congratulations also go out to our new NEG Secretary, BG (Ret.) Ray Davis, along with our new VP Chapters, COL (Ret.) John Broam and new VP Membership, COL (Ret.) Liz Martin. As I write this, our new NEG is meeting at the AAAA HQ in Connecticut to chart our path forward. More to follow on specific committee assignments, board appointments, etc., but I wanted to let you know that your NEG is assembled and moving out smartly.

If you have any ideas on how AAAA can serve you better, please contact me at walter.golden@quad-a.org

Above the Best!

Wally

Walter M. Golden Jr.

Major General, U.S. Army Retired

37th President, AAAA

Looking Back, June 2025

By Mark Albertson

Rover Joe, Horsefly, Timothy and Pineapple

As with any other endeavor that is from the mind of man, there is that period of trial and error until that level of efficiency is hopefully attained. This was certainly the case with trying to reach a functioning system of joint forward air controllers so as to provide the ground forces with effective close air support. Following the campaign in North Africa and the 35-day Sicilian operation that resulted in the removal of Axis forces, it was not until the Italian campaign that greater efforts were made to improve the functionality and coordination between ground and air for CAS.

An issue for improving close air support was motivating the Army Air Forces towards a more avid interest in same. For after the war, as pointed out by historian Harry Cole, “’it is obvious that at the time of the Sicilian campaign much remained to be done in the improvement and coordination of techniques of air operations in close support of ground forces.’ Tactical air control inefficiencies largely stemmed from American air commanders’ reluctance to become involved in the joint planning effort, which was an apparent result of the Mediterranean Air Command’s intent to assert its recently acquired autonomy. The situation only began to improve after U.S. Fifth Army Commander General Mark W. Clark made an emphatic request for better air integration, and Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower issued a virtual directive for a more active tactical air support role from the ‘so-called Strategic Air Force.’”[1]

Cooperation between air and ground forces improved. This despite the fact that German resistance caused the Allied advance up the Boot to slow and even grind to a halt, going into the spring 1944.[2]

Improved cooperation between ground forces and air staffs resulted in a command and control procedure that was sophisticated enough to accommodate the lowliest of requirements. Missions to be requested for action the following day would be sent up the food-chain of command until it reached the Corps level. Here staff would coordinate CAS requests with Army level. Army and air staffs huddled for evening meetings. Missions would be scheduled, depending, of course, on the availability of aerial assets.

But then there was the fluid situation, an urgent request for support from the front that required immediate attention. This was the “call request.”

“Call requests for air support against rapidly developing targets originated with a radio call from the front-line requesting agency to the division. The division immediately passed the request up to the joint air-army control center at the army headquarters, while the corps and army commands monitored the net, offering tacit approval for the request with their silence. Final approval for the request came from the army and air force operations officers at the control center. ‘Approved’ missions were tasked to air units operating on alert status in the air operations directive. Call missions frequently achieved their goal of having aircraft on-station within ninety minutes of the initial request. While formalizing the air tasking process greatly contributed to the operational availability of CAS aircraft, the introduction of forward air controllers enabled tactical air ground integration.”[3]

The forward air controllers were a tactical improvement for the integration of air-ground cooperation. AKA “Rover Joes,” their function was to insure the success of pilots answering the call-request owing to the lack briefing prior to the mission. Yet Rover Joes proved useful for scheduled missions or call-requests.

The Rover Joes were devised by the XII Air Support Command. These were generally made up of an Army Air Forces officer (pilot) and a ground forces officer working from a concealed position at the front. Hill tops were sought because of the advantage offered for a more commanding view of the battle area. “Their radio equipment, behind the hill out of sight of enemy observers and protected from enemy fire, was operated by enlisted personnel who communicated by telephone to the observation post.[4] Ground units seeking the elimination of attacking enemy forces or those enemy strongpoints offering resistance to an offensive were primary targets of opportunity.

The process entailed the ground forces, when seeking air support for the elimination of an enemy target, radioed the Rover Joe unit. Clearance was required by air and ground officers at the ground-air control center. Once this was done, the Rover Joe radioed the fighter-bombers which were nearby so as to conduct their attack.

The Rover Joe controller, using maps and aerial photographs, briefed the flight leader as to the features of the terrain as well as having the artillery mark the target area with colored smoke. The fighter-bombers would then give the target a going over with strafing runs and or bombing. The Rover Joe unit would then record the results of the attack. Indeed, the whole process could take less than 15 minutes.[5]

Direct radio contact between Rover Joe units and supporting fighter-bombers improved close air support efforts for the ground forces. Regardless, though, it was still not the adequate solution that was needed. Being on the ground, many times Rover Joe controllers and observers could not find suitable positions for observation. Many times the view was restricted to only several hundred yards of front. Hardly a panoramic view. British criticism included that the Rover Joe system worked better within static situations as opposed to actions of a more fluid nature, which could result in the bombing or strafing of friendly troops. What was required, then, was an unrestricted view, one that offered a constant visual contact of enemy positions. This could only be done from the air. This led to the introduction of the “horsefly.”[6]

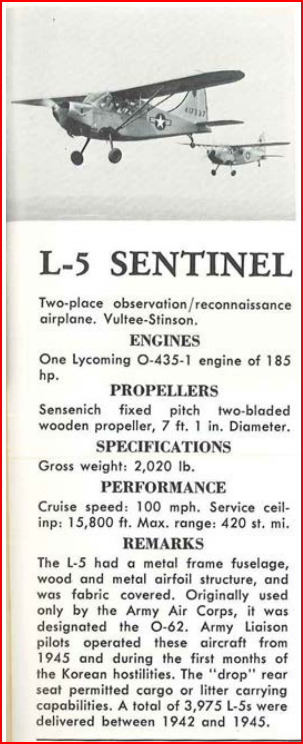

L-5 Sentinel Specifications

Horsefly planes were referred to as such in Army Air Force transmissions. Since they were needed close to the front, the horsefly operated off ground forces airstrips near the front lines. The Stinson L-5 was the plane and was usually flown by an AAF fighter-bomber pilot assigned on temporary duty and, was generally from the fighter-bomber squadron assigned for ground support operations. The observer was from the ground forces and from the unit to which the horsefly had been attached.

Horsefly aircraft were distinguished by stripes painted atop the wings, perhaps red or orange. Such would identify this particular liaison plane from any other along the same front.

Preparatory to each mission, horsefly crews were briefed. Maps and aerial photographs of the target in question were employed to ready the pilot and observer. Indeed, such briefings were the result of an aerial reconnaissance of the front conducted by the horsefly.

Once taking off, the horsefly rendezvoused with the fighter-bombers it was to direct behind friendly lines. Then it was on to the target.

Once at the target, the horsefly would direct the fighter-bombers by radio; and, if need be, mark the target with smoke grenades. At times, horsefly crews were only thirty feet from the ground when dropping smoke grenades so as to assure the destruction of the target.

“On 29 June [1944] an experiment was made using 1st Armored Division L-5s to direct fighter plane attacks. The controllers were air officers who flew in four L-5s, each painted a different color for identification (Horsefly Yellow, Horsefly Blue, etc.). The experiment was not considered a complete success, but it did prove the idea was practical.”[7]

The British were hardly keen on the horsefly principle, considering the ground observation principle more efficient despite its limitations. The Americans differed here as to the aircraft’s ability to offer a wider view of the battlefield. Americans thought, too, that the horsefly principle would prove more successful on a fluid battlefield. As to the vulnerability of the flivver plane, it was believed by Americans that the L-5 could operate at an altitude of 6,000 feet and five miles behind enemy lines. That is, of course, that air superiority had been established. And once into 1944, this was becoming and ever present reality.

Another attempt at establishing a functioning close air support technique was that of “Timothy.” This was first used in the Italian campaign on November 12, 1944, “when Desert Air Force Pilots provided close support for a British brigade offensive. An Eighth Army history states: ‘[It] took the form of a ‘Blitz’ in a limited area on either side of the brigade’s axis of advance, to a depth of about 1,000 yards, in front of a smoke bomb line. Three attacks had been prearranged (at 0730, 0830 and 0930) each consisting of 24 aircraft. Results were so good that the attacks were repeated. . . .’

“By the end of the day, the brigade had advanced 2,000 yards and taken 106 prisoners at a cost of 13 casualties. Timothy was undertaken again the next day with both British Spitfires and American P-47 Thunderbolts participating, and it continued to be used for the remainder of the campaign.

“Timothy’s essential prerequisite was that it had to be tied in with a ground offensive whose forces had to take immediate advantage of the air attack. The land formations had to furnish precise information on positions, targets and timing. It was also imperative that two safety factors be observed: (1) the local Rover must control the operation, ordering the smoke bomb line only after pilots had announced they were in the area, and then giving orders to attack and to cease; and, (2) pilots must be briefed not to attack unless both the smoke bomb line had been laid according to plan and Rover had expressly given his permission. This type of operation could degenerate into ‘area bombing’ rather than for an advance in a specific, heavily defended sector, but it did prove effective on a number of occasions.

“Another widely used technique, called ‘Pineapple,’ was designed to strike lucrative moving targets discovered by tactical aircraft on reconnaissance missions. Most often, the reconnaissance pilot radioed the army-air control center in the clear, indicating the target location, direction of movement, and composition. If the air force representative could accept the request for attack, the control center immediately passed it on to Pineapple-designated aircraft on alert, which at times were able to reach the target area within 15 minutes of receiving the order. The reconnaissance pilot would assist fighter-pilot pilots in locating the target. If the target was not clearly visible, the reconnaissance pilot might even lead the attacking flight to it. Occasionally, in addition to the control center, the reconnaissance pilot might contact a Rover for support. If the control center gave permission, Rover selected a rendezvous point from which the reconnaissance pilot picked up the fighter-bombers to lead them to the target. Since enemy ground or anti-aircraft fire could make an attack on the target too dangerous, the leader of the Pineapple flight could still the situation by using the code-word Nuts.[8]

Following the Allied success at Normandy, the horsefly continued to be used in France. This was particularly true with First and Third Armies. According to Ken Wakefield, “The Third Army employed Horsefly operations for the first time during its offensive in the Saar, two L-5s giving coverage from dusk to down. The technique was used with great success, the airborne controllers directing numerous fighter-bomber strikes against both pre-arranged and opportunity targets during the drive to the Rhine and beyond. The 9th Infantry Division also used its liaison aircraft to direct fighter-bomber attacks and found those against targets of opportunity, where there was no time to brief pilots, particularly rewarding. Approval of the method was also to be found in a report by VI Corps which stated that Horsefly was responsible for much effective bombing of Siegfried Line fortifications. In addition, vast amounts of enemy material was destroyed by air-directed close support in its drive to the Rhine and on into Bavaria and Austria. Nevertheless, Horsefly was not without its critics and there were those who favored control of fighter-bombers by similar high-performance aircraft; certainly, as the critics argued, Horsefly operations were feasible only where air superiority enabled slow, unarmed and unarmored aircraft to operate with relative immunity.”[9] Such criticism had dogged horsefly ever since it was introduced in Italy.

Of course, as with any other aspect found in war, horsefly was not without its human cost. Again, Wakefield: “On Christmas Eve (1944), Technical Sergeant Charles W. Leipersock, flying L-5 42-99605 on a Horsefly mission, with Major Randolph M. Jordan of the 10th Armored Division, failed to return to the squadron’s strip in Luxembourg. Sometime later it was learned that the L-5 had crashed near Ettelbruck, shot down in flames by flak. Sergeant Leipersock managed to bale out and was taken prisoner by a German tank crew, but nothing further is known of Major Jordan. Later at the end of April 1945, Charles Leipersock was released from captivity by the Third Army and was flown back in an L-5 from Landshut, Germany, for a memorable reunion with his squadron colleagues.”[10]

Data: Republic P-47 Thunderbolt

The razor-back P-47D, with its eight .50 caliber machine guns. At 17,500 full-load tons, the Thunderbolt was the heaviest single-engine fighter in World War II. Indeed, the P-47 was only 4,000 pounds less than the twin-engine Bristol Beaufighter.

The P-47 Thunderbolt was a fighter plane, bomber escort and utilized as a fighter-bomber for the interdiction role and close air support. The “Jug” was rugged yet speedy and with its eight .50 caliber machine guns packed a lethal punch. At seven and one-half tons, it was the heaviest single-engine fighter of World War II. And in its ground-support role, P-47s could take a punch. This writer knew a P-47 pilot who flew 85 missions in ground-support. His plane was replaced five times; but, all of his rides, shot up as they were, got him home.

| Power plant | One 2,535 hp Pratt & Whitney R-2800-59 Double Wasp Radial. |

|---|---|

| Wing span: | 40 feet, 9 inches. |

| Length: | 36 feet, 1 inch. |

| Height: | 14 feet, 2 inches. |

| Weight empty: | 10,700 pounds. |

| Weight loaded: | 17,500 pounds. |

| Crew: | 1 pilot. |

| Max speed: | 433 mph at 30,000 feet. |

| Service ceiling: | 42,000 feet. |

| Normal range: | 590 miles. |

| Armament: | Eight .50 caliber machine guns; up to 2,500 pounds of bombs or ten Rockets.[11] |

A diving P-47 Thunderbolt loosing missiles at a ground target.

According to data supplied by Republic Aviation Corporation, the P-47 during “World War II dropped 132,482 tons of bombs, expended over 135 million rounds of ammunition and some 59,567 rockets and several thousand gallons of napalm. 3,752 enemy aircraft were claimed to be destroyed in the air, and a further 3,752 on the ground. This effort required 1,934,000 flying hours and 204,504,000 gallons of fuel.

“Two-thirds of all P-47s produced eventually found their way to USAAF units in combat theaters, and losses of aircraft on operational missions were only 0.7 percent of those dispatched. From D-Day to V-E Day in Europe, the P-47 low level strikes accounted for 86,000 railway wagons, 9,000 locomotives, 6,000 armored vehicles and tanks, and 68,000 motor trucks. The total P-47 production consisted of 15,683 aircraft, some 31 Thunderbolt groups being in action in 1944.”[12]

Endnotes

[1] See page 28, Chapter 2, Literature Review, World War II, “Rebuilding the Joint Airborne Forward Air Controller Analyzing Joint Air Tasking Doctrine’s Ability to Facilitate Effective Air-Ground Integration,” by Major David Scott Chadsey, USAF, 2013.

[2] Fifth Army’s way to Rome was blocked for weeks owing to the German control of the commanding heights of Monte Cassino. “Monte Cassino—Monastery Hill, as it became known to the men of many nations who fought under its shadow for so many weeks—completely controlled both the valley that lay before it and also the Liri River to the northwest. Route 6 runs up to, then around the foot of the southern flank of Monastery Hill, having passed through the little town of Cassino which itself snuggles under the haunches of the 1,600 foot hill. From the summit of Mount Cassino, an observer could watch any movement in both the valleys, and by artillery and mortar fire seal off the vital artery to Rome, Route 6.” See pages 18 and 19, Chapter 2, “The Germans Come to Cassino,” The Battles for Cassino, by Brigadier General E.D. Smith.

[3] See page 30, Major David Scott Chadsey.

[4] See page 209, Chapter 5, “Allied Cooperation in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1945,” Case Studies in the Development of Close Air Support, edited by Benjamin Franklin Cooling.

[5] The British employed a like system to Rover Joe. Though when dispatching support aircraft it was generally six fighter-bombers as opposed to the American four aircraft. See page 209, Benjamin Franklin Cooling.

[6] See page 93, IV, “Couriers and Angels,” Jeeps in the Sky, by Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Ten Eyck.

[7] See page 144, Chapter III, “The War Years, North Africa, Sicily and Italy,” The Army Aviation Story, by Richard Tierney with Fred Montgomery.

[8] See pages 218 and 219, Benjamin Franklin Cooling.

[9] See page 118, Chapter Eighteen, “16th December 1944-25th January 1945: The Battle of the Bulge and War in the Rhineland,” The Fighting Grasshoppers, by Ken Wakefield.

[10] See page 123, Ken Wakefield.

[11] See page 141, “Republic, P-47 Thunderbolt,” Aircraft of World War II, by Kenneth Munson.

[12] See pages 14 and 16, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, Described, Part I, by Geoff Duval.

Bibliography

Cannon, Hardy D., Box Seat Over Hell, San Antonio, Texas, June 1985.

Chadsey, Major David Scott, USAF, “Rebuilding the Joint Airborne Forward Air Controller Analyzing Joint Air Tasking Doctrine’s Ability to Facilitate Effective Air-Ground Integration,” U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, December 13, 2013.

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin, editor, Case Studies in the Development of Close Air Support, Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force, Washington, D.C., 1990.

Duval, Geoff, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, Described, Part I, Kookaburra Technical Publications, Dandenong, Victoria, Australia, 1969.

Eyck, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Ten, Jeeps in the Sky, Commonwealth Books, New York, 1946.

Greenfield, Kent Roberts, Colonel of the Infantry, Army Ground Forces and the Air-Ground Battle Team Including Organic Light Aviation, Study No. 35, AD-A954 913, Historical Section, Army Ground Forces, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1948.

Love, Terry M., L-Birds: American Combat Liaison Aircraft of World War II, Flying Books International, New Brighton, Minnesota, 2001.

Munson, Kenneth, Aircraft of World War II, Ian Allen, Great Britain, 1962.

Raines, Edgar F., Eyes of Artillery: The Origins of Modern U.S. Army Aviation in World War II, CMH Pub 70-31-1, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 2000.

Smith, Brigadier General E.D. Smith, The Battles for Cassino, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1975.

Tierney, Richard with Montgomery, Fred, The Army Aviation Story, Colonial Press, Northport, Alabama, 1963.

Wakefield, Ken, The Fighting Grasshoppers: U.S. Liaison Aircraft Operations in Europe, 1942-1945, Mid Counties Publications, Leicester, England, 1990.

As I scribe my last message as your AAAA National President, all indications are that we will have an exceptional Summit, just given the level of attendee registration and the record exhibit commitments from industry and our other partners; and the strong support from our Army and Aviation Branch leadership to develop and deliver a comprehensive and meaningful agenda and program of activities which showcase the strength of the entire Army Aviation community and family. In addition, we will also induct our newest Army Aviation Hall of Fame members, recognize our many outstanding individual and organizational Aviation awardees, and importantly, simply spend time together socially and professionally as a committed community.

This is what the AAAA Missional Solutions Summit is all about, the sole Army Aviation event that brings together our entire community to engage on how best to support our Army, our Branch, and most importantly, our Army Aviation soldiers and families. “Army Aviation: Ready to meet Tomorrow’s Challenges Today” is a most appropriate theme and I want to thank our Branch Chief, MG Clair Gill, for all his support and guidance, along with all the other members of the Aviation General Officers Steering Committee, in the lead up to this years Summit.

I also would like to thank the Branch Chief and the other Aviation GOSC leaders for joining MG (Ret.) Todd Royar, Mr. Bill Harris, and myself at the April 9 ‘re-boot of the Congressional Army Aviation Caucus on Capitol Hill. Well over 125 folks attended the networking reception in the Rayburn Building, to hear from our Caucus Co-Chairs, Ranking Member on Appropriations, Hon. Rosa DeLauro, (D-CT-3), and Hon. Dale Strong, (R-AL-5) along with MG Gill who laid out the Branch priorities, along with remarks from each of the Aviation GOSC leaders.

Well, as I alluded to above, “commanders come and go, and it doesn’t hurt the organization any!” Hard to believe that my term as your AAAA President is ending… time goes by in the blink of an eye. What a privilege it has been! I want to thank the National Executive Group (NEG) team; we could not have a more dedicated, engaged, and supportive group of committed, ‘Soldiers for Life.’ MG (Ret.)Wally Golden, our Senior VP (about to become your AAAA President), thank you for everything and especially for stepping in for me at last year’s event in Denver. BG (Ret.) Tim Edens our Treasurer, and MG Todd Royar our National Secretary, thank you also for all your efforts in keeping this great organization focused, successful and relevant. CW4 (Ret.) Becky Chambers our VP for Membership has done a record-setting job driving us to over 20,000 members and LTC (Ret.) Jan Drabczuk, our VP for Chapters, has managed his own record by growing our AAAA chapters to an all-time high of 83. Amazing results from an amazing team. Again, thank you all… and that goes to the entire AAAA National Executive Board which includes our many Committee Chairs … your committed service to the Association is remarkable!

And finally, my personal thanks to Mr. Bill Harris, our Executive Director, Janis Arena, CW4 (Ret.) Joe Pisano and the entire AAAA professional staff. You all are the Association’s center of gravity and heartbeat… the reason that ‘we are who we are’…completely committed and dedicated to the mission of our great Association and making things happen! Thank you!

As a soon to be a Past AAAA President at the conclusion of this Summit, I will remain engaged as Chairman of the Nominating Committee and look forward to contributing however I can to this great organization whose sole focus is “Supporting the U.S. Army Aviation Soldier and Family”

Above the Best!

MG Walt Davis, U.S. Army Retired

36th President, AAAA

walt.davis@quad-a.org