Looking Back, September 2023

By Mark Albertson

80th Anniversary of World War II

Army Aviation: Italian Campaign

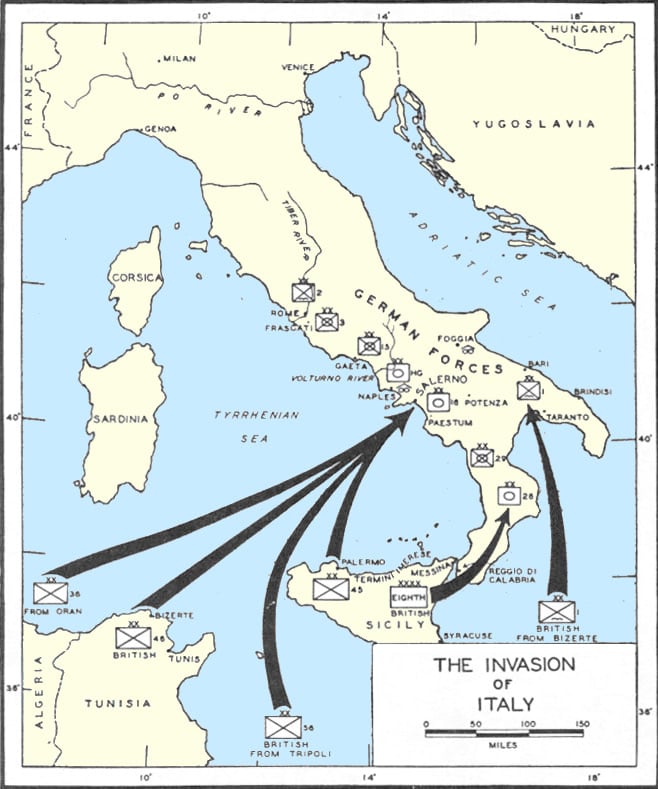

September 3, 1943, the main weight of the British Eighth Army on Sicily crossed the Straits of Messina to establish a toehold on the Italian mainland. On September 9, elements of Eighth Army and 1st Airborne Division landed at the port of Taranto. That same day, General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army landed up the coast at Salerno.

Opening phases of the Italian campaign, featuring the invasion routes by Anglo-American forces.

Opening phases of the Italian campaign, featuring the invasion routes by Anglo-American forces.

“Fifth Army air artillery officer, Major John T. Walker, organized the Fifth Army Air Observation Post Section into two subsections: one dealing with operations, initially under Captain Gillespie [Eugene p.], and second with maintenance and supply, under Lieutenant Strok.”[1] The latter choice brings to mind the supply problems which existed during the North African campaign, with spare parts at a premium and a supply situation being less than desirable since it was the Army’s first major campaign of the war. Michael J. Strok, who for want of a better description can be viewed as a “scrounge,” organized Fifth Army’s Artillery Air Depot (Provisional). Strok’s efforts at “Keepin’ ‘em Flyin’” made up for the lack of support from the Army Air Forces, which was playing catch up as well. Strok not only organized maintenance schedules, but provided such services as safety bulletins and registering aircraft losses. Strok was able to acquire a few L-5s—in direct contravention to the Army Air Forces’ restriction limiting the Air OP to the L-4 Cub.

The work horse for the Air Observation Post, the ubiquitous L-4 Cub.

The work horse for the Air Observation Post, the ubiquitous L-4 Cub.

Paul De Witt observed that the primary task of the Air OPs at Salerno was to provide artillery fire direction. He also noted that early on in the operation, field commanders determined their front lines by using Cub pilots for reconnaissance. Five L-4s were sent aloft daily, at first light, to reconnoiter assigned sectors.

Later when crossing the Volturno River, Air OPs were employed to pinpoint German forward elements, which were then mapped for later pounding by the Field Artillery. Tank destroyer units and reconnaissance battalions would borrow Cubs from their division’s artillery and use them for recon purposes. The importance of Army aviation to combat operations was becoming readily apparent.[2]

On January 22, 1944, Operation: SHINGLE, an Anglo-American force stormed the beaches at Anzio in an effort to flank General Albert Kesselring’s defense line. The Germans held the high ground, an advantage countered by the Air OPs flying reconnaissance for the assault units.[3]

Regardless, the slugfest on the hotly contested beachheads caused heavy casualties among the assault forces. Blood was desperately needed for the wounded. Cub pilots, Lieutenants Paynee O. Lysne and Richard W. Blake, flew in 50 pints of blood to the Anzio beachhead. “In less than 24 hours after the plea had been sent, life-giving blood was being administered.[4]

As Allied troops fought hard to expand their beachhead and move inland, Army aviators helped to fend off German counterattacks. Captain Willian H. McKay, of Fifth Army, spotted a German force moving towards the beaches. Some 2,400 troops, backed by tanks, were suddenly bludgeoned by a 5,000 round downpour of American ordnance. A German officer, later captured, offered that casualties were upwards of fifty percent as a result of the lethal cooperation between McKay and the Field Artillery.[5]

Lieutenant Frank A. Perkins and his observer flew artillery missions at Anzio. The observer directed coordinated gunfire for American and British artillery and warships lying offshore. Two Italian towns, Littoria and Adria were reduced to rubble. These efforts extended to the nocturnal adjustment of artillery fire, from Anzio up to Cassino. At Anzio, Captain John W. Oswalt, 1st Armored Division Air Officer, focused 370 guns on a single target. Included here was naval gunfire from several cruisers, USS Brooklyn, HMS Dido and HMS Orion.[6]

Moonlight sometimes brought Cubs out like vampires. Distinct features betrayed themselves to the aviators, such as towns, rivers, coasts and road bends, which enabled the Air OPs to sharpen nocturnal bombardments. Returning Cubs were directed earthward by those on the ground armed with flashlights, who illuminated otherwise invisible strips.

A customer of the Air OPs, a 155 mm Long Tom in action, Nettuno area, February 1944.

A customer of the Air OPs, a 155 mm Long Tom in action, Nettuno area, February 1944.

German ground forces urged the Luftwaffe to hurry the eradication of the troublesome Cubs. The dilemma proved problematic. From the time a Cub had already completed its mission and had returned to base, or was on its way to another sector, it had already vacated the area in which it had been operating in. However because of the low operational altitude of the Cubs and the attendant anti-aircraft protection, enemy fighters had to be piloted by airmen of skill and daring so as to be able to down the elusive Cubs. The Luftwaffe even resorted to bogus messages of fighter direction to prompt Cub pilots to vacate patrol areas.

Air OPs pushed the envelope by flying deep into enemy territory. This drew fire from anti-aircraft batteries and even ground troops. To avoid damage aviators would push over to the deck and hedgehop their way to safety; or, simply zigzag out of harm’s way.[7]

Another German countermeasure was to locate the lairs of the pint-sized pests and bomb them; or, if possible, shell them. Like ground troops, Air OP personnel had to make sure that slit trenches and fox holes were dug. Planes were dispersed and camouflaged. And, if need be, contour flying on and off strips to prevent their location by the Germans.

A perspective on German efforts to counter the Cubs is offered by Howard Rudd, a veteran news correspondent and former Air OP aviator, reflecting on German fighter tactics. “German fighters in daytime were not a serious problem after North Africa, where the Luftwaffe lost air superiority forever. Some German fighter units did develop tactics to cope with L-4s: Two fighters attacked straight on, two from above and two from below. This usually brought down the L-4, but there were never enough German fighters available on the Western Front to make the technique widespread. The fact that it was used at all, tying up six scarce and valuable fighters against feeble, eight hundred dollar L-4s, is an indication of how the L-4s hurt the Germans.[8]

The Luftwaffe apparently concurred, showing how the cost outweighed the benefits. Fifteen Bf-109s were lost, resulting in seven pilots killed in exchange for eight Air OPs downed, not a very good swap.[9]

* * * * *

June 4, 1944, General Mark Clark made his triumphal entry into Rome. However, two days later, the spotlight focused on France with the Normandy invasion. This did nothing, though, to alleviate the fact that the Italian campaign was still a slugging match. Yet Anglo-American forces battling on the Boot were consuming German divisions that would have been employed elsewhere, such as in France or the Eastern Front.

The mountainous terrain made Close Air Support a problem, to the extent of producing friendly fire incidents. 1st Armored Division commander, Major General Ernest N. Harmon, threatened to shoot down Army Air Forces aircraft. However a solution presented itself.

An enterprising Captain John Oswalt, managed to acquire several L-5s. AAF pilots flew these aircraft which were equipped with VHF radios. Colored wing tops, Red, Yellow, Blue, etc., distinguished the liaison planes. The idea was to employ the Stinsons to direct fighter-bombers onto targets stalling the ground advance. Known as the Horsefly, “Flying Jeeps,” would perform the same function as the “Rover Joe” system of ground-based observers, mobile teams of radio-equipped Jeeps providing direction for fighter-bombers onto targets of opportunity. The ground-based observers were fighter-bomber pilots.

The Stinson L-5, the plane the Army Air Forces did not want the Air OPs to have. Yet despite advantages of range, altitude, power and speed, the L-4 Cub proved the heart and soul of Ground Forces’ organic aviation; and, set the stage for the Army Aviation branch to come.

The Stinson L-5, the plane the Army Air Forces did not want the Air OPs to have. Yet despite advantages of range, altitude, power and speed, the L-4 Cub proved the heart and soul of Ground Forces’ organic aviation; and, set the stage for the Army Aviation branch to come.

In the mountainous Italian terrain, the slow-flying liaison aircraft provided an advantage. Besides directing fighter-bombers onto ground targets, Horsefly assets determined friendly from enemy units for both air and ground forces. Continuous Horsefly patrols provided daily updates on targets of opportunity; kept advancing units apprised of natural obstacles and impediments affecting the line of march; much like the Air OPs, Horsefly missions were also found to deter German artillery fire for fear of revealing positions to American counterbattery fire.

Drawbacks included a vulnerability to enemy flak and fighters, so air superiority was a prerequisite. And repeated use of Horsefly provided that indication of impediments to fighter-bomber activity.[10]

Of greater significance, here, was the prospect of L-5s operating under the control of Army aviators. Beginning in North Africa, with light aircraft beginning to show real promise in Ground Forces operations, requests began to filter in for the L-5s, since the more powerful engine enabled the Stinson to operate in higher climes than the L-4, which in comparison was underpowered. Both the War Department and the Army Air Forces conspired to prevent the Air OPs from attaining an aircraft of higher performance.

Fort Sill was training Air OP pilots with the L-4. And since this was so, it was considered expedient to deploy aviators in the same aircraft under combat conditions. There were also production concerns, since the Army Air Forces needed the Stinsons to equip their liaison squadrons. And lastly, the War Department frowned on the Ground Forces’ upgrade since the L-5 needed more runway for landings and takeoffs; and, was less adept at avoiding enemy fighters as opposed to the Cub.

Another issue affecting the Ground Forces was that of photo reconnaissance. Ground Forces units resorted to L-4s for terrain photography; since the Army Air Forces efforts with this tactical chore had fallen short. 1st Infantry Division urged that photographic equipment be made available to the Air OP. The Field Artillery Board tested photographic equipment aboard

Cub aircraft and solicited the War Department to attach photographic capabilities to the Field Artillery Headquarters and batteries. The Army Air Forces disagreed.

Photoreconnaissance was among the duties within the tactical responsibilities of the Army Air Forces. The War Department turned down the Ground Forces’ request. The Air OP’s raison d’etre was the direction of artillery fire; while snapping pictures and seeking aircraft of greater sophistication and performance was moving beyond the original intent of Ground Forces aviation.

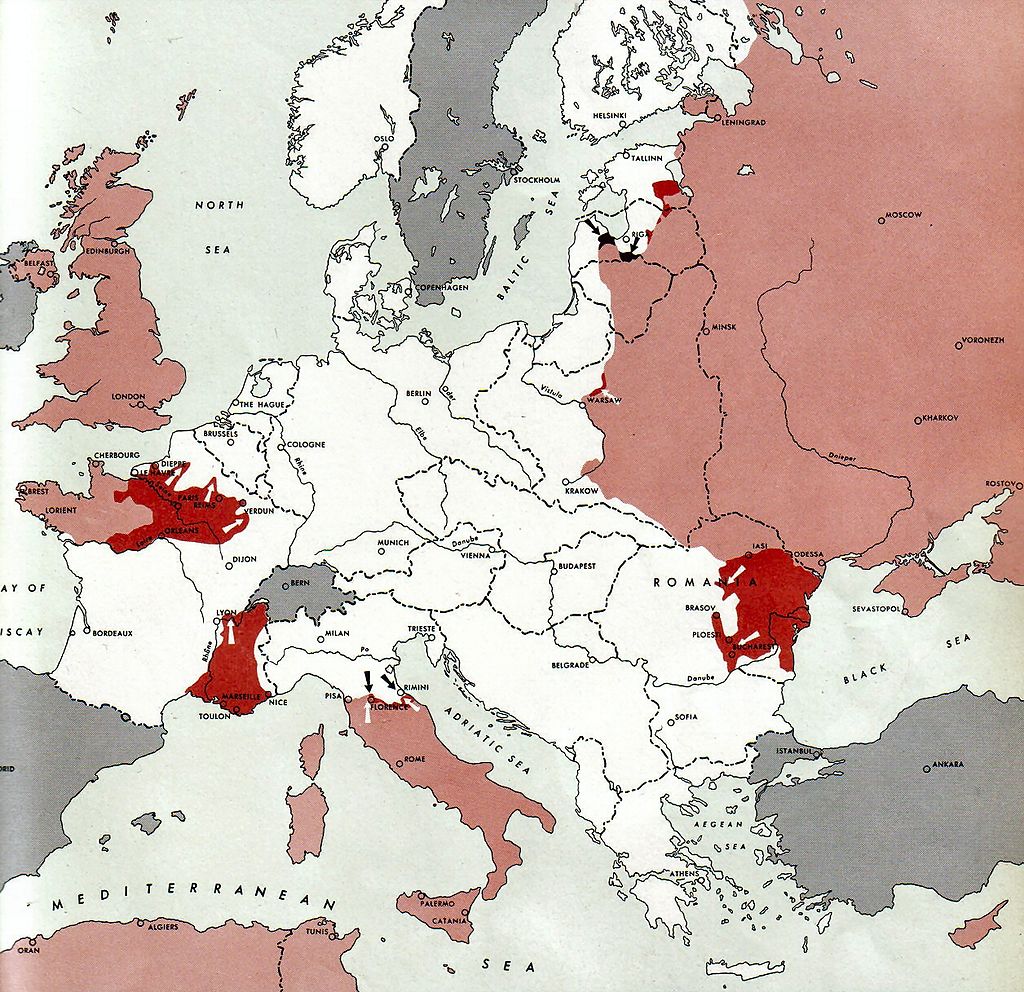

The status of the Italian campaign, September 1944.

The status of the Italian campaign, September 1944.

* * * * *

Sky-Jumping Cubs

By December 1944, Fifth Army was north of the Arno River, occupying mountains south of the Po Valley. The mountainous terrain presented difficulties for Fifth Army commander, General Lucian Truscott,[11] and so persuaded him to address the issue. Truscott ordered Captain Jack Marinelli, air officer of the Fifth Army, to build a strip close to the CP. The ground settled on provides an intriguing piece of engineering.

The strip was laid out on a mountainside, with a downhill slope for takeoffs and an uphill run for landings. The runway stretched 735 feet by 30 feet; and, was 97 feet higher on the upside than on the cliff side, which featured a ski jump, the lip of which overlooked a valley some 2,000 feet below.

“The interesting feature,” according to Colonel Marinelli, “was that we had to use full throttle to taxi to the top of the strip and landing. But you could also take off down the strip without power.”[12]

* * * * *

Endnotes

[1] See page 166, Chapter 5, “Initial Deployment and Combat in the North African and Mediterranean Theaters,” Eyes of Artillery: The Origins of Modern U.S. Army Aviation in World War II, by Edgar F. Raines, Jr.

[2] See pages 38 and 39, “The Air OP of the Armored Artillery,” Military Review, Vol. XXIV, No. 6, September 1944, by 1st Lieutenant Paul DeWitt, instructor in Department of Air Training, Field Artillery School, Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

[3] See page 48, Chapter 4, “Air Observation Posts,” A History of Innovation: U.S. Army Adaptation in War and Peace, U.S. Army Center of Military History, by Jon T. Hoffman, General Editor.

[4] See page 43, “The Army Aviation Story,” Part VI, The War Years: North Africa, Sicily, Italy, U.S. Army Aviation Digest, 1962, by Richard K. Tierney.

[5] See page 106, “The Most Lethal Plane in the World,” Mr. Piper and His Cubs, by Devon Francis.

[6] See page 84, Richard K. Tierney.

[7] See page 276, “Air OPs . . . ,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 34, No. 5, May 1944, by Major Edward A. Raymond, FA.

[8] See page 4, “When I Landed the War Was Over,” American Heritage, Vol. 32, Issue 6, October/November 1981, by Hughes Rudd.

[9] See page 271, “Air OP Causes Trouble: Extract From the History of the German Fighter Force in Italy,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 36, No. 5, 5 May 1946.

[10] See pages 14-17, Part Two, “Horsefly Control of Fighter-Bombers,” Liaison Aircraft With Ground Forces Units, United States Forces, European Theater, Study N. 20, 1945, U.S. Army Center of Military History, August 4, 1998.

[11] On November 25, 1944, General Mark Clark was ordered to relinquish command of Fifth Army and take over 15 th Army Group; which meant command of Allied armies in Italy. General Lucian Truscott assumed command of Fifth Army. See page 170, Chapter Nine, “Starving Time: The Failed Advance and the Second Winter,” Flawed, but Essential: Mark W. Clark and the Italian Campaign in World War II, by Jon Mikolashek.

[12] See page 138, “The War Years: North Africa, Sicily and Italy,” The Army Aviation Story, by Richard K. Tierney with Fred Montgomery.

* * * * *

Bibliography

“Air AP Causes Trouble,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 36, No. 5, U.S. Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., May 1946.

DeWitt, Lieutenant Paul A., “The Air OP of the Armored Artillery,” Military Review, Vol. XXIV, No. 6, Command and General Staff School, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, September 1944.

Francis, Devon, Mr. Piper And His Cubs, The Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1973.

Greenfield, Colonel Kent-Roberts, Inf. Res., Chapter VII, “Practical Steps Toward Air-Ground Cooperation,” Army Ground Forces and the Air-Ground Battle Team, Including Organic Light Aviation, Study No. 35, Historical Section, Army Ground Forces, Department of the Army, Fort Monroe, Virginia, 1948.

Headquarters, 34 th Infantry Division, APO 34, U.S. Army, Italy, “Lessons Learned in Combat, November 7-8, 1942 to September 1944—Algiers, Fondouk, Cassino, Anzio, Rome, Hill 609, Benevento, Civitavecchia, Volturno River, Cecina, Rosignano, Mt. Pantano, Livorno,” September 1944. Source: Charles L. Bolte papers, Box 6, U.S. Army Military History Institute Library, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania.

Raines, Edgar F., Jr., Eyes of Artillery: The Origins of Modern U.S. Army Aviation in World War II, Army Historical Series, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 2000.

Raymond, Major Edward A., FA, “Air OPs . . . “ The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 34, No. 5, U.S. Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., May 1944.

Rudd, Hughes, “When I Landed The War was Over,” American Heritage, Vol. 32, Issue 6, October/November, 1981, www.americanheritage.com/when-i-landed-war-was-over

Tierney, Richard, with Montgomery, Fred, The Army Aviation Story, Colonial Press, Northport, Alabama, 1963. Introduction by, General Mark W. Clark.

Tierney, Richard K., 20 th Anniversary of Army Aviation: Part VI, “The Army Aviation Story,” U.S. Army Aviation Digest, Fort Rucker, Alabama, November 1962.

Vance, William E., “History of Army Aviation,” U.S. Army Aviation Digest, Vol. 3, No. 6, U.S. Army Aviation School, Fort Rucker, Alabama, June 1957.