By GEN (Ret.) Richard A. Cody, LTG (Ret.) J. Mark Curran, and LTG (Ret.) James J. Lovelace: From 2003 through 2012, the Army was at war. The Global War on Terrorism began in earnest following the attacks on 11 September 2001. After the Battle of Anaconda, Operation Enduring Freedom settled into combat and stability operations. As early as 2002, the U.S. military had begun to turn its attention to Saddam Hussein and the removal of his weapons of mass destruction. In early 2003, the Army deployed a large number of combat formations into Kuwait, poised just across the border from Iraqi Armed Forces. The Army, along with its Marine Corps and our British Allies, supported by the greatest Air Force and Navy in the world, staged for a conventional fight, a fight for which they had trained for decades. Little did our leaders know that this campaign would last for almost 10 more years while morphing into a large scale counter insurgency/counter terrorism; that it would result in the greatest Transformation of the Army since World War II; that our Army would conduct three force surges into Iraq to defeat Al Qaeda; and, ultimately as we withdrew from Iraq, find the U.S. military surging back into Afghanistan. During this period, Army Aviation was either deploying, deployed, redeploying or training to deploy. In spite of this unrelenting OPTEMPO, our Aviation units remained unequivocally the best trained, best equipped, best led Aviation force we had ever sent into sustained combat. The Army did this while simultaneously transforming to the Modular Force, modernizing its equipment, drawing down forces in both Europe and Korea, growing all components of the Army and expanding our Special Force formation, executing Base Realignment and Closure and responding to the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Consequently, Army Aviation and Special Operations Aviation found themselves heavily committed to combat and counter insurgency operations around the globe, but predominately in Afghanistan and Iraq which are two of the harshest environments for rotary wing aircraft.

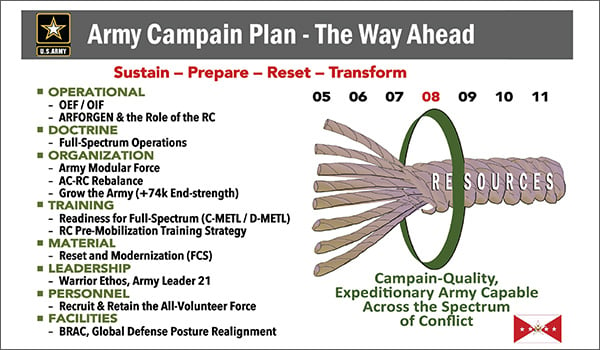

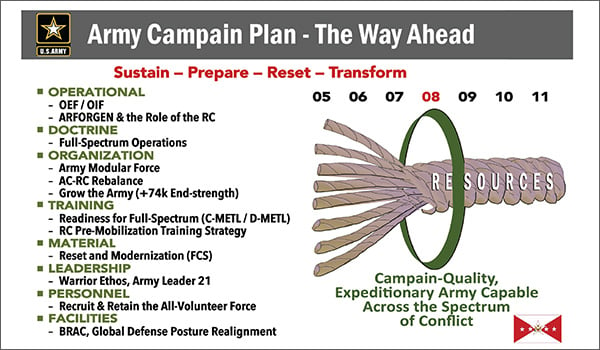

The Army’s posture, in terms of doctrine, organization, training and equipment, was suited for operations in 2002. However, by the end of 2003, as Iraq evolved into a counter insurgency operations (COIN) and Afghanistan operations expanded with the resurgence of the Taliban and continued operations to search out and destroy Al-Qaeda, the Army’s force posture faced serious challenges across doctrine, organizations, training, leadership, personnel and facilities (DOTMLPF). Not only had the focus of combat operations shifted, but the terrain, distances and expansive operational environment associated with COIN and stability and support operations placed new demands on the Army’s air and ground Soldiers, equipment, platforms and command and control (C2). The Army had to adjust its strategic force structure aim point across the entire DOTMLPF and grow in depth. Due to the environmental demands of both theaters of war, Army ground and air platforms had to materially adapt. More powerful engines, better survivability equipment, smarter weapons, better sensors, new intelligence techniques and more effective command and control systems like Command Post of the Future (CPOF) are just a few examples. The Army rewrote its COIN doctrine to apply to the operational environment which dominated through the rest of the decade. Figure 1, “Army Campaign Plan – The Way Ahead” gives insight into the expansiveness of the changes that were required.

This shift placed more demand on the adaptability, flexibility and utility of Army Aviation. Aviation became a critical enabler to the Army for maneuver, responsive fires, sustainment and medical evacuation. In Afghanistan nothing moved without air. In Iraq, with the threat of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), air transport became even more critical to moving key personnel, supplies and equipment. Operations demanded all components of the Army and Army Aviation to sustain the operational tempo and duration of the operations. At its peak, operations required multiple multi-component combat aviation brigade task forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. Additionally, the enduring U.S. commitment in the Balkans and the Sinai continued to require the support of aviation task forces. Aviation forces, predominately from the National Guard, were also called upon for disaster relief and humanitarian assistance throughout the decade for events like hurricane Katrina and Unified Response to Haiti. This unprecedented demand for Army Aviation assets often translated to dwell time for active units of 1:1 and for reserve component units 1:3 or less. Demand for units following the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom grew so high that a new Army Force Generation model had to be adapted that essentially placed army and aviation units on a prepare, deploy, recover, redeploy cycle. Similarly, special operations units were deployed on a continuous basis requiring some unique ideas to meet demand.

U.S. Army Soldiers of the 101st Combat Aviation Brigade sit aboard a CH-47 Chinook helicopter during infill operations in the Arghandab area, Kandahar, Afghanistan, Oct. 21, 2010. / U.S. ARMY PHOTO BY SPC IAN SCHELL

To sustain the fight and meet the operational requirements of Iraq and Afghanistan, aviation units had to take on several adaptations across the DOTMLPF and across operational procedures never before practiced. All required a synchronized effort on the part of Aviation commanders, operators, trainers, logisticians and acquisition experts with the support of the Army staff. As part of the Army’s Campaign Plan, the Army published the “Army Aviation – Way Ahead” (figure 2) in 2004 that portrayed a list of action items that needed to be executed in a coordinated DOLMPF way. From 2004-2008, the Aviation “Six Pack” consisting of the Aviation Commandant; the Program Executive Officer (PEO) Aviation; the Director, Army Aviation (G3); the commanding generals of Aviation and Missile Command (AMCOM) and Army Special Operations Aviation Command (ARSOAC); and Mr. John Shipley, Aviation Applied Technology Directorate (AATD) met monthly with the Vice Chief of Staff Army (VCSA) to synchronize this major effort,. The “Six Pack” duties insured that all actions across the Aviation DOTLM-PF could sustain the current fight and future modernization post the Comanche termination decision.

Doctrine Tactics and Techniques

The Army published its new Operations manual (FM 3.0), Stability Operations manual and modular force construct in 2008 to address the new realities. It called for Army Aviation to play a greater role in supporting direct fires for widely distributed ground platoon, company and battalion formations. It called for more lift support to move and sustain ground formations and more MEDEVAC to operate over extended distances. Aviation became the critical enabler to conduct distributed operations. Combat aviation brigades found their battlespace expanded in support of operations calling for change in the organizational construct of aviation units. Following the Army’s lead, our Aviation Commandants spearheaded a comprehensive relook of Army Aviation Doctrine. New doctrine was written to address Army Aviation’s contributions, in support of the Army and Joint Force, across the full the Spectrum of Conflict – ranging from Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HA/DR), to Stability and Support Operations (SASO) to Counter Insurgency Operations (COIN) to Conventional Offensive and Defensive Combat Operations to Major Theater Warfare (MTW) full spectrum conflict.

The new doctrine and realities of operations in Iraq’s and Afghanistan’s highly complex environments placed more demand on Battle Command down to the platoon level and required the aviation commander to have battle command systems that provided him greater situational understanding across an expanded battlespace to effectively support the ground brigade combat teams.

Tactics had to be adapted to meet the theater demands for Counter Insurgency Operations (COIN) in desert terrain in Iraq and southern Afghanistan but also the mountainous terrain of eastern and northern Afghanistan. Running and diving fire became the most used methods for engaging the enemy. For the Apache, the modernized target acquisition device (MTADS) brought additional tactics, techniques and procedures (TTP) changes by providing greater standoff and visibility through a significantly improved sight. Air ground coordination became critical down to the individual squad’s calls for fires in close combat attack and in close proximity to friendly forces. Training in these technics was developed and practiced in theater, not only with American units, but allies as well. Procedures for terrain flight were modified for urban areas to avoid being targets to MANPADS, RPG and small arms fire. Where possible, routes were consistently varied to avoid patterning and air ambush. The introduction of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), focused in the Army on reconnaissance, surveillance and target acquisition (RSTA) in support of ground formations, led to the emergence of new TTPs discussed later. So rigorous were some of the TTP changes that several programs in development during the decade had major relevancy and affordability issues raised, particularly in terms of range, payload at higher altitudes and temperature.

Organization

By 2004 the Army was on its way in executing the most comprehensive reorganization since the 1980s transitioning to a Modular Force while collapsing the Army’s operational structures from four to three by eliminating the Army echelon and thus collapsing down functions to corps and divisions or units of employment (UE). Fighting units, or units of action (UA), brigades and battalions were modularly designed to facilitate rapid force tailoring and supplement each other. Aviation units likewise became modularly designed to facilitate rapid task organizing and designated Units of Action with pure aviation battalions, but tailorable to rapidly form multifunctional aviation task forces. Given the aviation requirements to simultaneously support stability and support operations and COIN over extended distances, this modular design was paramount. The result was the Multifunctional Aviation Brigade (MFAB) latter to be merely recognized as combat aviation brigade (CAB). The CAB included its own intermediate level aviation support, the aviation support battalion (ASB). The ASB was designed modularly as well to support aviation operations over extended distances tailorable to support Aviation task forces. The CABs incorporated UAS at the CAB level and later at the attack and reconnaissance squadron level. UAS were also organized into the new modular brigade combat team (BCT) for RSTA. The change in aviation structure was perhaps the largest since the 1960s. The formation of the MFABs doubled the number of aircraft and personnel and aligned with every Division, with some having more than one. Units often transitioned to the new structure between rotations. To facilitate better liaison, brigade aviation elements (BAE), led by an experienced Aviation Major and manned with a tactical operations (TACOPS) warrant officer, operations sergeant and two aviation operations specialist, was assigned to the Modular BCT to work with the brigade commander and S3. By 2004 the BAE handbook was already published and used to train both BAEs and maneuver brigades on the value and employment of the BAE. BAE integration became an important aspect of BCT mission rehearsal and train-up for deployment and therefore challenged extensively at the combat training centers (CTCs).

MEDEVAC Part of the CAB

In the process of organizing the 2004 MFAB, MEDEVAC was added within each CAB. A 12 helicopter MEDEVAC company was organized within each divisional CAB’s general support aviation battalion along with C2 Black Hawks and CH-47 Chinooks. This ensured that each CAB would have embedded MEDEVAC capability for their supported BCTs. The MEDEVAC company was also organized to be tailorable and task organized to an Aviation task force. In both Iraq and Afghanistan, given distances, limited ground routes, and a 360-degree battlefield, aerial evacuation was critical to saving lives. Nested within the command and control of Aviation TF and linked to the supported ground force, teamed with armed aerial escort, MEDEVAC crews remained situationally aware and superbly executed casualty evacuations to medical care facilities saving countless lives. The development of TTPs, FLIR sensors and on board medical trauma treatment greatly improved MEDEVAC capabilities during the decade. Known as the “Golden Hour,” the hour of time from an incident to a patient receiving trauma care, remained the driving standard for Army MEDEVAC crews to execute their missions. Afghanistan posed a huge challenge, yet Army Aviation MEDEVAC crews consistently met the standard.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

In 2003 the Aviation Center assumed proponency for unmanned aerial systems. In coordination with the other TRADOC centers, the Aviation Center oversaw and led significant improvements in UAS equipment, safety, standards and combat applications. In 2003 the Army had only 13 UASs. By 2010, the Army had flown over a million UAS hours and used over 333 different UAS platforms in operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. By the end of 2012, the Army operated five primary UAS systems. These were the older MQ5B Hunter, the MQ1C Gray Eagle (first fielded to CABs in 2012), the RQ7 Shadows (first fielded in 2002 to BCTs and air cavalry squadrons) and hand launched RQ11 Ravens and RQ20 Pumas (first fielded to ground companies in 2005). Throughout the decade it became evident that teaming manned platforms with unmanned aerial platforms for reconnaissance and surveillance offered great promise. As the equipment matured, so did the concept for linking the two for RSTA operations.

TF ODIN

Insurgent use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) became one of the biggest killers of U.S. and Allied forces on the battlefield. The enemy employed them as a strategic and tactical weapon very effectively. Emplaced along main supply routes, these command or remotely detonated devices inflicted heavy casualties on Allied forces. Adopting aviation technics first applied in Viet Nam, the Army developed a counter to the IED named TF ODIN in August 2006. Equipped with unmanned RSTA platforms and manned ISR fixed wing aircraft, TF ODIN began surveillance operations along the MSRs to detect and destroy IED emplacers, track bomb makers and destroy IED factories. TF ODIN consistently honed their skills and employed more sophisticated sensors that vastly cut down on IED casualties. A second TF ODIN was later deployed to Afghanistan to address IED and counter rocket and mortar threats there as well. TF ODIN also served as prototyping platform for developing teaming between manned and unmanned aircraft to perform RSTA.

TF ODIN fixed wing aircraft began teaming with UASs through the TF ODIN operations center for surveillance operations. In addition, TF ODIN demonstrated the ability to cue an Apache or Kiowa Warrior to a target under surveillance by a UAS to engage it. This built upon capabilities being developed for Comanche to team with UASs in real time. At the Manned Unmanned Systems Integration Capability (MUSIC) in 2012, Aviation and Missile Research, Development and Engineering Center (AMRDEC) demonstrated the ability to direct and view the sensor on a UAS from a Kiowa Warrior and an Apache. This capability, called Manned Unmanned Teaming (MUMT), demonstrated the potential to team manned platforms and unmanned platforms in the reconnaissance and attack missions and further demonstrated significant promise for further advancing robotics on the battlefield to augment and complement aviation. The next step in MUMT evolution is to give the Apache the ability to control the flight path of a team UAS and see and control its sensor in the cockpit. TF ODIN and MUMT were yet again another example of Army Aviation adapting to enemy tactics with successful results.

TF 160th Expansion

OPTEMPO for conventional and SOF aviation forces remained high through 2010 and the end of Operation Iraqi Freedom. The demand and pace for Special Operations forces and TF 160th continued to remain extremely demanding conducting global operations. Often Special Operations, particularly in Afghanistan, had to be augmented by conventional Army Aviation to meet Special Operations demands. The continuous need for Special Operation Aviation into the foreseeable future demanded that TF 160th grow. In October 2007, the addition of another battalion was approved. Moreover, the TF developed and expanded its own UAS capability with outstanding results. Modernization of the TF remains a key consideration of the Aviation Branch as it forges into the future. Importantly, TF 160th has often blazed the path to new aviation capabilities. The relationship between conventional Army Aviation and Special Operations Aviation continued to grow throughout the decade and lessons are now easily shared among the communities.

Training

During the preparation phase of ARFORGEN, training often included new equipment training (NET). However, the most significant change in Aviation training was the phased introduction of Flight School XXI (FSXXI) at Ft Rucker. Beginning with implementation in 2003 through 2006, Ft Rucker changed its Initial Entry Rotary Wing training to produce more ready pilots in their “go to war” aircraft by leveraging high fidelity simulation; a single primary aircraft for basic, instrument, and combat skills; and more time in a pilot’s “go to war” aircraft. It included basic officer leader training, survival, evasion, resistance, and escape (SERE) training, Dunker training; the results which produced pilots in a shorter period. This paid huge dividends to an aviation force in combat as new pilots could become integral crew members faster in units deploying or already deployed. As tactics evolved in theater for missions, they were incorporated in flight training. FSXXI removed a significant training burden from already over taxed units. Also introduced in 2003 and used throughout the decade at unit level was the Aviation Combined Arms Tactical Trainer Aviation or (ACATT-A). This four-cockpit, reconfigurable collective trainer was the first collective trainer for aviation units. It came with a built-in after action review capability and could link to ground collective simulators. It augmented individual trainers provided by aviation platform programs such as the Transportable Black Hawk Operations Simulator, Longbow Cockpit Trainer and Transportable Flight Proficiency Simulator (TFPS).

An AH-64D Apache from Company B, 1st Attack Battalion, 227th Aviation Regiment, 1st Air Cavalry Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, flies over a residential area in the Multi-National Division-Baghdad area Oct. 12, 2007. / PHOTO BY CW4 DANIEL MCCLINTON

Aviation Training Exercises (ATX), first started to prepare CABs for Bosnia, continued to be conducted by the Aviation Center to train CABs for operations in Iraq or Afghanistan as part of their train-up for deployment. Conducted at Ft Rucker using constructive simulations, role players and a version of AVCATT-A, these exercises proved invaluable especially for training multi-compo CABs.

The combat training centers also retooled to train COIN and facilitate mission rehearsal exercises to prepare units for Iraq or Afghanistan. Aviation participation with the BCTs became key for ground commanders to hone air ground coordination and rehearse the use of Army Aviation. The CTCs also facilitated integration of the new brigade aviation element (BAE) into the BCT which helped the BCT commander and S3 take full advantage of aviation support, manage airspace, and assist with UAS operations.

Equipping

One of the earliest acts in 2003 of the new CSA, General Pete Schoomaker, was to convene an Aviation TF under General JD Thurman and BG EJ Sinclair to review the current status of Army Aviation in light of the dynamic changes facing the Army over the next decade. The CSA directed a holistic review of Army Aviation and make recommended changes to the Army’s current Aviation strategy. The TF recommended changes across Aviation’s entire DOTMLPF to address the immediate future and new threats. One of its many solid assessments was that aviation modernization was underfunded and over 40% of aviation modernization was tied up in one program, the Comanche. Consequently – a follow on review of the Comanche. After multiple restructures, Comanche (started in 1983 as the Light Helicopter Experimental or LHX program), had morphed over the years into an armed reconnaissance helicopter program. The RAH-66 Comanche was probably the best helicopter ever built, however the stealthy helicopter was no longer viable given current and projected costs and threats and the need to modernize the entire Army Aviation Fleet following 10 years of meager investments. Therefore, the Aviation TF and a follow on review of specifically the Comanche recommended its cancellation and that the funding be made available to address several other Army Aviation modernization shortfalls. A Presidential decision in February 2004 ended the program but the Army was permitted to retain $14.6 billion in Comanche funding to apply to the recapitalization of other aviation programs. Shown on the “Fixing Army Aviation While Supporting Combat Operations” chart (Figure 3) one can see the impact of the Comanche decision.

As a result, the Army, over the next several years, was able to buy an additional 796 upgraded Black Hawks, Apaches and Chinooks as well as provide upgraded engines and ASE to some 1400 aircraft. The AH-64D Block II program started in 2003 and UH-60M fielding began in 2006. CH-47F, OH-58D, C-12 modifications and variants continued throughout the period. The LUH began fielding in 2006 followed by C-27J in 2007. The C-27J was needed to replace the Army’s fixed wing cargo aircraft, the Sherpa, and to relieve some of the burden placed on the CH-47 fleet delivering logistics the “last tactical mile.” The ‘hub and Spoke’ aerial resupply mission was to be fielded in the Army National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve Aviation Companies of 8 C-27J aircraft with a cargo handling platoon; unfortunately, the C-27J program was transferred to the U.S. Air Force in 2010 and subsequently cancelled. Funding for advancing UASs accelerated, specifically Shadow and the new Gray Eagle. In 2004 the Army began to immediately address shortfalls in aircraft survivability equipment (ASE) for deploying units.

The Comanche decision left funds available to start a new, but less sophisticated, Armed Scout Helicopter Program. The ARH70 program addressed a need for 368 aircraft to replace ultimately the OH-58D Kiowa Warrior. Unfortunately, this program was cancelled in 2008, but the requirement remained extant. Other aviation systems modernization was addressed to include Air Traffic Services equipment and ground support equipment. Fueled by funding from the Comanche decision and Overseas Contingency Operations Funds (OCO), the decade saw a significant Army Aviation modernization effort. Of note, this effort modernized all components of Army Aviation. We used Army National Guard AH-64As to feed the Block II AH-64D line and replaced in the National Guard with Block 1 AH-64Ds. The National Guard units received more L model Black Hawks as National Guard aviation units enjoyed equipping at the same level of their Active counterparts. The proverbial “potholes” in Army Aviation modernization were being addressed. Units were not only rotating in and out and in again to combat operations, but they were often being modernized and trained on new equipment in between rotations while their aircraft were reset.

Initial unit deployments into theater were of a traditional nature. But it soon became evident that the high demand on national transportation assets, in and out of theater would force aviation units to deploy without all of their equipment, including aircraft. Eventually, rotating onto Stay Behind Equipment (SBE) became the norm. Still, falling in on aircraft and equipment left in country by preceding units challenged aviation leaders, particularly with respect to maintenance and supply accountability. Pride of ownership was no longer one of the driving factors in executing superb maintenance. Critically, commanders and aviation leaders at all levels overcame this challenge, as evidenced by the tremendous operational readiness rates.

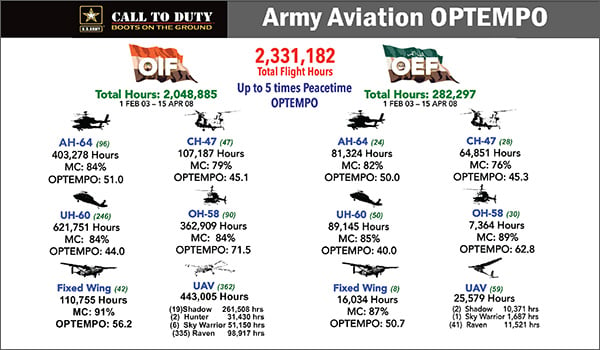

Leader recons, right seat rides and contractor logistics support facilitated transition between units. The high OPTEMPO led to a substantial need for contract maintenance support at all levels. Industry stepped up and provided thousands of mechanics to augment unit maintenance performing phases and battle damage repair. After a few rotations it became clear that in-country aircraft, operating in dirty environments, high-pressure altitudes, hot conditions and at high OPTEMPO, would need a substantial reset above the unit level. AMCOM established several reset sites where, after a few rotations, select aircraft were redeployed and reset. This reset included battle damage repair, application of modification work orders (MWOs) and, in some cases, depot level repair. So Army Aviation found itself maneuvering equipment as well as units, quite a different process than ever before envisioned. And, they did so while executing combat operations at an extremely high OPTEMPO. As a snap shot, Figure 4, “Army Aviation OPTEMPO,” shows by 2008 the Army had flown over 2.33 million hours in OPERATIONS IRAQI FREEDOM and ENDURING FREEDOM (OIF/OEF).

Leadership and Personnel

During the decade several branch officers rose to the highest ranks and were recognized across the joint community for their tactical and technical skills. In both the Army and Special Operating forces, branch Aviation officers could be found serving in senior positions. Aviation warrant officers continued to demonstrate their prowess as aviation warfighters, technicians and leaders. In 2003 the Aviation Branch Chief recognized the criticality of warrant officers to the Branch by establishing a Chief Warrant Officer of the Branch position and selecting CW5 Steven T. Knowles as the first Chief Warrant Officer of the Branch. The Aviation Branch has had a CWOB ever since to help lead Army Aviation and now several other Branches have established branch chief warrant officers – to include the Chief of Staff of the Army. Recognizing the important contribution that our warrant officer Warfighters make to aviation operations, survivability and electronic warfare, the first Tactical Operations Officer school and skill identifier was established in May of 2003 for warrant officers. Warrant officers began being placed in table of organization (TOE) leadership positions, especially important in the UAS community. During the decade the Aviation enlisted MOSs went through several changes, coming together under the Career Management Field 15 to include UAS, air traffic control (ATC) and ASE.

The heroics and sacrifice of Army aviation Soldiers throughout the decade have been chronicled in Hall of Fame inductees and in awards and decorations for heroism. Many have paid the ultimate sacrifice in service to our Nation, Army, but most importantly to the ground soldier for which Army Aviation exists to serve. By the end of 2012, nearly 200 Army Aviators had given their lives in combat in service to their ground soldier and thousands of soldiers are alive today because of the efforts of Army Aviation’s attack, lift, and MEDEVAC aircrews. If you want to know how Army Aviation has performed and continues to perform in peace and war, ask a ground combat veteran. Their critique is Army Aviation’s proper judge of performance.

Facilities

Army basing, both in the United States and overseas, experienced changes for Army Aviation. From 2005 to 2012, The Army executed a major Base Realignment and Closure that impacted the home stationing of several Army Aviation units. In addition, between 2003 and 2012 a major drawdown in forces in Europe occurred which repositioned two CABs from Germany to the U.S. Often these relocations occurred between deployments to Iraq or Afghanistan. In the Pacific, in support of U.S. global force repositioning, drawdowns occurred in Korea, reducing the forces on the peninsula while also repositioning them to new installations. By the end of the decade, Korea had only one CAB – inclusive of a rotational Kiowa Warrior cavalry squadron. By 2004 operations had ended in Bosnia relieving the need for American aviation support in the Balkans; Kosovo operations ended in 2013. So by 2012, Army Aviation force posture was predominantly based in the U.S. (including Alaska and Hawaii) and overseas with one CAB in Korea and one CAB headquarters plus in Germany.

For Army Aviation, basing and bed-down in theater (i.e., Iraq, Afghanistan, Bosnia, Kosovo) was provided in forward operating bases (FOBs) often constructed with portable clam shell hangars, Army engineered wooden buildings, or containers. Where available old airfields were used and every attempt was made to move to hard stand areas to conserve engines and to operate UASs. Maintenance of aircraft and equipment was a 24-7 operation to meet the high aviation OPTEMPO and to battle the austere conditions for Army helicopters. The churn of global force posturing and base relocation was yet another challenge for the Army and its aviation.

The decade between 2003 to 2012 was a historic period for Army Aviation. Given the new realities of a series of long wars, characterized by stability and support and counter insurgency operations, the Army and Army Aviation had to adjust its force structure aim point and adapt across the total force, Active, Guard and Reserve. No part of Army Aviation was left untouched. By 2012 Army Aviation was still transforming and executing combat operations in Afghanistan in support of their ground brethren with skill and determination while looking ahead into the future of Army Aviation.

Author Note: “A History of Army Aviation: From the Beginnings to the War on Terror” by Dr. James W. Williams, was used as a reference for portions of this article.

GEN (Ret.) Richard A. Cody is a Master Army Aviator and the 31st vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army; LTG (Ret.) J. Mark Curran is a Master Army Aviator and former Army Aviation Branch Chief; and LTG (Ret.) James J. Lovelace is a former Director of the Army Staff and Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, U.S. Army.