Looking Back, May 2025

By Mark Albertson

80th Anniversary of World War II:

Army Aviation: The Pacific Theater

Combat conditions in the Pacific Theater of Operations differed from those in the European Theater. From the start, the war in the West was, for the most part, of a conventional type: Infantry, artillery, armor, used on a scale not seen in the Pacific. From the North African Desert, onto Sicily, up the Italian boot and across the French countryside into Germany, armies were employed on a level conducive to the precepts of maneuver and mobility, combining ground power with airpower as the Allied advance rolled up the outnumbered German armies.

In the Pacific it was a different story. The Allied strategy was based on naval power. As the United States Navy recovered and rebounded from the debacle at Pearl Harbor, Allied fortunes rose, spurring success after success. In other words, the Island-Hopping Campaign. Unlike the more conventional approach to war in the ETO, the Allied approach to war in the PTO amounted to a modern version of Siege Warfare. As the U.S. Pacific Fleet wrested control of the world’s largest ocean from the Imperial Japanese Navy, control of the seas reduced Japanese island bastions to hopeless positions of encirclement, condemning ill-fated garrisons to the dismal prospects of starvation when bypassed or certain destruction when Allied troops stormed ashore.

Early stages of the Island-Hopping Campaign did not see the mass employment of troops as compared to the ETO. For instance, the fall of 1944 there were forty U.S. Army divisions in the ETO as opposed to 21 in the Pacific, plus six Marine Corps divisions. Twenty-four divisions of the U.S. Army formed a strategic reserve.[1] It was really not until the latter stages of the campaign that an ETO equivalent of troops was committed in the Pacific, such as in the Philippines and Okinawa.[2]

In the PTO, many of the combat environments were jungle infested. This rendered difficult the employment of artillery. For instance, “In the initial island-to-island warfare, where difficult jungle terrain was often encountered, flash ranging was found impractical and was not attempted . . . On the other hand, sound ranging provided an excellent means of locating Japanese artillery and the adjusting of our artillery.”[3]

An example of operating in a dense jungle environment was New Guinea. So thick was the tangled jungle canopy, that it was not uncommon to find forward observers better able to direct artillery fire. Still intruding Cubs proved enough of a nuisance to garner the attention of prowling Zeros; for the Air OPs quickly became associated with the accuracy of the Field Artillery.

But uses for Cubs were found beyond that of their original intent. Being a rain forest, roads in New Guinea were rare and those that existed quickly became quagmires following heavy rains. Cubs were pressed into service as air taxis, hauling brass, delivering messages, moving supplies, transporting wounded in addition to reconnaissance and patrols.

Air OPs were employed to direct counterbattery fire onto Japanese gunners shelling American barges moving supplies along the coast; and, conversely directing American artillery onto Japanese barges.

Needless to say that in this jungle nightmare, there was always something for the Cub pilots to do. Captain Edwin Leer, a December 1942 graduate of Fort Sill, commanded a group of five L-4B Cubs, four sergeant pilots and himself. In the course of 2.5 months in the New Guinea jungle, Leer and his fliers logged 956 hours.[4]

A projected use of the Cub was flying “top cover” for an amphibious landing. “Just as the Lae show was getting under way it was found that the Jap might have evacuated Salamaua. No one was sure, however. (If you do not know Jap fire discipline and camouflage, such a situation may be hard to visualize.) Our forces slowly pushed in toward the town while 3 barges with assault troops were dispatched for a diversionary landing on the beach in front of the town itself. The barge-borne outfit would need plenty of help if the Jap was waiting, so it was decided to use a Cub for ‘top cover’—our artillery being registered on a base point near the beach, the Cub would fly in with the barges and direct fire in case of opposition. Undoubtedly the idea would have worked, but no opposition was encountered.”[5]

In the Philippines, spring 1945, from Loacan air strip, near Baguio, Air OPs of the 33rd Infantry Division, operated off an air strip some 4,000 feet up in the rugged mountains of Luzon. The aviators did more than fly artillery fire direction missions; they developed their own photographic section, scrounging equipment wherever possible. So successful was this effort in initiative that the Sixth Army artillery officer suggested that the practice be carried out in other divisions.

The forbidding terrain compromised close air support for the troops battling the stubborn Japanese. Cubs were thrown into action as pathfinders for bombing attack, dropping smoke grenades to mark targets for destruction. In 40 air strikes, this aerial combination resulted in no friendly fire incidents. Likewise Cubs were employed to lead C-47 pilots to their proper drop zones in the mountains so as to resupply troops on the advance. This enabled the supply planes to better navigate the mountainous terrain and deal with the hazardous air currents.[6]

But Leyte was more than just rugged mountains with hazardous air currents. Like New Guinea it was home to the ubiquitous jungle. And this is where the 11th Airborne Division found itself, slogging its way through the rainy, muddy, disease-ridden wallow to root out the entrenched Japanese. Liaison pilots found themselves supporting their comrades-in-arms in this fetid wasteland. As noted by Major Edward M. Flanagan, Jr., F.A., it “is the story of the overworked artillery air fleet doing a steam shovel’s job with a spoon.”[7]

To move supplies through the jungle, logs were used to cover the mud-caked roads. This did not always work, the logs sometimes sinking into the morass from the weight of the trucks. The Carabao, the indigenous pack animal used in the jungle, proved limited on the steep mountain tracks, which sometimes proved little better than inclined stream beds during torrential downpours. The troops themselves could not carry much in this unforgiving environment. Aircraft, though, proved invaluable.

The impenetrable Leyte jungle restricted drop zones or clearings for C-47s to adequately supply the troops. Not so the flivver planes. At Manarawat, a field dug out of the jungle was able to handle Cubs. Aviators flew in sections of a portable hospital which was then constructed. Doctors saved the lives of many wounded, sometimes operating under flashlights. Some of the wounded were delivered to doctor’s care by Cubs, thereby avoiding time-consuming treks through the jungle.

From the division artillery air fleet, some nine Cubs and 7 L-5s were put to work, delivering arms, ammunition and supplies to troops advancing in the Leyte jungles. At one point, the flivver planes delivered 21 tons a day, in a performance that would herald the work of rotary wing aircraft and crews in Korea and Vietnam.

Perhaps the last words are from a mortar platoon leader, when he wrote, “The liaison plane performed an outstanding job of resupplying the advance elements in the mountains. The difficulty of locating units in their small areas and the continuous bad weather made the liaison plane very effective. Their slow speed and maneuverability made them much more effective than higher performance aircraft.’[8]

China-Burma-India Theater

In the often referred to “Forgotten Theater” of war, the Army Air Forces was the primary employer of light aircraft. For instance L-4s and L-5s were used to fly engineers in an out of construction sites during the building of the Ledo Road—through northern Burma for the link up with the Burma Road from Lashio to Kunming—the epic supply route to the hard pressed Chinese Nationalist forces.[9]

Second most used Army cooperation aircraft of World War II and, will see duty in the Korean War. Used by the AAF, AGF and the Navy for aerial reconnaissance, medical evacuation, aerial taxi, . . . Appeared in almost every theater in World War II.

The L-1 or O-49 was found to be useful in the rugged Asian continent. While the C-47 proved invaluable for its trips over the Hump, delivering supplies and evacuating wounded, the L-1 proved invaluable in local evacuations, its power plant able to hoist it above much of the area’s mountainous terrain. Conversely, liaison pilots braved the hazards posed by the lower altitudes to airlift supplies, facing violent air currents which could send a flivver plane cascading out of control into a sheer mountain face or spiraling into the jungle floor below.

Seen as the plane that was America’s answer to the superlative Fiesler Storch, the plane proved to heavy for the Air Observation Post squadrons at 3,325 gross pounds, besides being more expensive that the L-4. The L-1 found a home in the CBI Theater, with its power plant able to hoist the plane over some of the mountains in-theater and able to effect medical evacuations and light-transport duty.

Transporting of wounded became virtually a matter of life or death in the impenetrable jungle. Backwater hospitals were linked by light planes making repeated runs to and from combat zones, airlifting foot sloggers in need of doctor’s care. The rudiment of the later Dustoff squadron in Vietnam can be found in the CBI. And examples abound:

“In response to a desperate plea for help from a big British force trapped in the Arakon area of southern Burma, seven light planes and nineteen sergeant pilots in fifteen days evacuated seven hundred casualties—with British Spitfires flying cover.[10]

OSS member, Richard Dunlop, related a rescue of a B-25 crew that had crashed into a swamp some 20 miles north of Myitkyina, ” . . . and Dennis Francis and a party of Kachins hurried to the scene from Arang. They found the crew alive but in terrible condition. There was no possibility that they could survive a trip by surface over the Mogaung Valley’s precipitous trails, so Francis and the Kachins hastily leveled a meager three-hundred-foot-long airfield in the patties . . . and a liaison pilot named Anderson flew his two-seater L-1 in from Myitkyina to pick up the injured fliers. He made five trips, a trip for each man, bringing them all out to Myitkyina from where they could be flown to the hospital in Ledo.[11]

Yet whether in or out of the CBI, it was not all doom and gloom in the PTO; there was a lighter side, even in that giant whirlpool of war. “General Joseph ‘Vinegar Joe’ Stilwell, Commander of Tenth Army, used Cubs extensively during operations in the Pacific. He enjoyed riding with the Air OPs with the windows open. On one occasion he was being flown by SSgt. Lyle W. White on a mission off Okinawa. A gust of wind blew through the Cub’s cockpit and the general’s battered campaign hat that he had worn for over 20 years, blew out the window.

“General Stilwell sadly watched his hat float down and plop into the sea. He remarked, ‘I’d sure like to go down there and rescue my old friend.’ Upon landing, Stilwell offered $25 to anyone who recovered the hat; much to his delight, it was returned to him 4 hours later.”[12]

Postscript

This is the sixth and final chapter of the “80th Anniversary of Army Aviation in World War II —or what it really was, the Air Observation Post. Reference to the entire series can be found rostered in endnote number 13.[13]

On December 8th, 1941, the Air OP’s sole reason for existence was for the aerial direction of artillery fire. And the platform of choice was the L-4 Piper Cub, an aircraft which appears in the annals of Army Aviation and, which can be construed as having changed the course of the history of the tactical air branch of the United States Army. The first being the gas bags of the Balloon Corps followed by the Cub; succeeded by the UH-1 Huey, which in turn will be followed by the AH-64 Apache. Each is emblematic of the distinct phases which mark the Saga of Army Aviation.

The ubiquitous Cub was the Air OP’s plane of World War II. Inexpensive, easy to maintain and fix, able to operate from unpaved strips near the front, the versatile Cub proved able to perform a variety of labors, including its primary task, the aerial direction of artillery fire. Served in both World War II and Korea. Piper’s Cub as that second aircraft in the development and evolution of Army Aviation. Shown here are a pair of Cubs operating off a jungle strip in the Pacific.

The gas bags of the Balloon Corps marked the Army’s first organized attempt into the realm of airpower, predominately for the purposes of aerial reconnaissance followed by modest attempts at the aerial direction of artillery fire. But the tethered balloon embodied the lack of mobility during the first half of the War Between the States; precisely the factor which would justify the comeback of the static balloon some fifty years later on the Western Front. But with the advent of mobility returning to the battlefield in 1863, Union generals steeped in the Napoleonic-Jomini tradition of arms relied on swift moving cavalry formations to conduct reconnaissance as well as maneuver warfare.

The Balloon Corps was the Army’s first sojourn into ‘airpower.’ Tethered balloons were utilized for aerial reconnaissance and the early attempts at the aerial direction of artillery fire. As the Union Army took control of the war by 1863 and mobility was becoming decisive, the labor-intensive balloons were seen as an impediment by the more reactionary of the officer class. Cavalry was still seen as that arm of reconnaissance and shock. Yet the seeds for the future were being planted, 1861-1863. Lowe’s balloons must be seen as the first aircraft in that evolution in the development of tactical aviation in the United States Army that will eventually result in the Air Observation Post, which will become Army Aviation itself. Pictured is Thaddeus Lowe going up in a balloon during the Battle of Seven Pines, June 1, 1862.

The L-4 Cub, though, provided that mode of mobility needed for the Field Artillery to effect the aerial direction of artillery fire within the confines of modern conventional warfare. Easy to maintain and cheap to manufacture, the Cub represented that vehicle of mobility that would form the basis for a tactical air capability for the Ground Forces, a giant step forward. For it was almost certain as sunrise that with the advent of the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1941, and the wider field of opportunity that was provided for the strategic employment of airpower during World War II, that a separate branch known as the United States Air Force was a foregone conclusion.

So to for the Ground Forces. The Air OPs proved their worth to the extent that other branches of the Army desired their services or clamored for their own capabilities, such as the Infantry and Armor. For besides directing artillery fire, Air OPs conduced aerial observation, aerial photography, route-column control, cabbie service for brass, medical evacuation, courier service, light conveyance of supplies, as well as directing attack aircraft and fighter-bombers in strikes against ground targets. “’The effectiveness of air-ground cooperation is still in its infancy. Air and ground commanders must be constantly on the alert to devise, and use, new methods of cooperation.’ These words, written by General George S. Patton, Jr., in 1945 and published in his book, War as I Knew it, are still worth our attention.”[14]

Yet a major contributor to the future course of Army Aviation were those actions taken by those inspired to arm their Cubs for combat. Enterprising individuals looking to turn their putt-putts into war machines . . . that is, of a sort, firing .45s out of the cockpit or affixing bazookas and even missiles to the wings. In Italy, for instance, Cubs from the Fifth Army were prepped to launch a bombing raid. “With all systems go, the attacking L-4s putt-putted up to the green Auscente Valley in their usual lackadaisical manner, then suddenly they shifted direction and raced, with what for them was phenomenal speed, over the target area. Each pilot carried a five-gallon tin can of gasoline mixed with oil on his wing strut and at the precise moment, he shoved it off with his foot. Most of the ‘bombs’ landed well outside the target area.”[15]

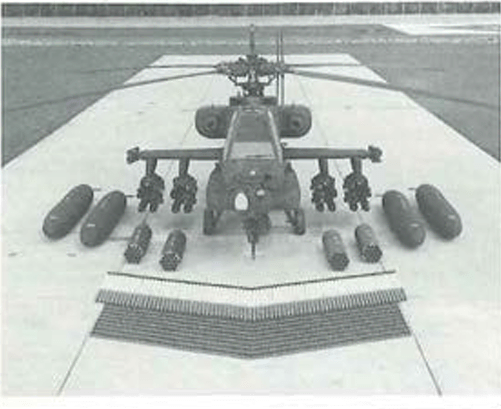

The AH-64 Apache attack helicopter. The fourth aircraft that made Army Aviation what it is. The Apache is a lethal aircraft able to support the ground soldier as well as being effective against enemy armor.

The arming of Cubs for action against the enemy amounted to little better than mosquitoes attacking an elephant. But such episodes of individual initiative were hardly examples of comic relief; rather, these efforts were examples of Yankee ingenuity and independent thinking (usually frowned upon by reactionary types). For in the end, perhaps the arming of Cubs displayed a deep-seated distrust of the Air Force agenda. And for those ready to disparage such thoughts need to be mindful of the actions taken by “Vanderpool’s Fools,” 11 or 12 years down the road. This, then, should make it obvious that not only were the airmen in the Army Air Forces looking to create an independent service, but the seeds were being planted for an autonomous aviation branch within the Army to take its place alongside the Infantry, Armor, Signal Corps, etc. The first attempt to create something resembling autonomy for airpower was in 1914, with the actions of Lieutenant Paul Beck and Congressman James Hay; though it was reaching critical mass by 1945.[16] And by 1947, with the National Security Act, the U.S. Air Force took it place alongside the Army and Navy as a separate service. But differences of opinion concerning roles and missions would not end with the divorce from the Army. And as with many broken marriages, disagreements continued for years. Hence the use of Cubs for the evacuation of wounded or to pick up and drop off personnel, which accurately forecast the Army’s use of the Huey to perform the same tasks on a more massive scale in Vietnam; as did the arming of the Cubs showcase the future employment of the AH-64 Apache by the Army to handle its version of close air support of the foot soldier. Classic examples of how history repeats; of course, the repetition is never exact, but it does repeat. Or if you are a disciple of Mark Twain, history rhymes.

The third of the decisive aircraft in the history of Army Aviation, the UH-1 Huey, the workhorse of the Airmobility Concept during the Vietnam War.

It is undeniable that the actions of the Air OPs to competently perform tasks other than that of the aerial direction of artillery fire broadened the appeal of Army Aviation; an appeal that would serve to bolster the post-World War II fortunes of Army Aviation . . . an appeal that would be advanced by the helicopter.

We begin with the Sikorsky VS-316, a platform based off the VS-300 prototype. A contract was signed with the Army Air Corps on January 10, 1941. And the VS-316, better known as the R-4, became acknowledged as the world’s first production helicopter.

On May 13, 1942, test pilot Les Morris took off from Bridgeport, Connecticut for a long distance flight to Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio. “The trip took five days and covered 761 miles. The elapsed time was 16 hours and 10 minutes in a series of 16 separate flights. A ‘chase’ vehicle (a sedan with 4 passengers) . . . with a large yellow circle painted on the roof accompanied the XR-4. Igor Sikorsky flew with . . . Les Morris from Cleveland to Mansfield, Ohio and the final leg from Springfield to Dayton, Ohio. The XR-4 arrived in Dayton on May 17, 1942 and was accepted by the Government on May 30, 1942. During the trip two unofficial records wee set: A distance record of 92 miles (Mansfield to Springfield) and an endurance record of one hour and 50 minutes.”[17]

Igor Sikorsky, with Coast Guard Commander Frank Erickson at the controls of a Sikorsky R-4 helicopter, August 1944. The R-4 was the first true production helicopter. Little used in World War II, the helicopter will find acceptance during the Korean War. It will be during the Vietnam conflict that the Bell UH-1 Huey will become the workhorse of the Airmobility Concept and therefore, become that third aircraft most important in the ongoing evolution of Army Aviation.

Captain Frank Gregory, USAAF, who was responsible for helicopter development for the Army, conducted shipboard tests from the tanker, Bunker Hill, in Long Island Sound off Stratford, Connecticut. Twenty successful liftoffs by Captain Gregory showcased the potential maritime utility of rotary wing aircraft.[18]

The first actual combat rescue mission was flown by 2nd Lieutenant Carter Harmon, USAAF, April 26-27, 1944. Behind enemy lines in Burma, were three wounded British commandos and the USAAF pilot sent to effect their rescue, all left stranded when their L-1 had gone down in the jungle. Liaison planes kept the men supplied for four nights. Harmon, meanwhile, had removed the co-pilot’s seat from his YR-4 so as to accommodate four Jerry cans for another 21 gallons of fuel. He took off from Lalagat, India, flying a route which included scaling a 6,000 foot mountain range. He made four trips to extract those trapped.[19]

The shades of Vietnam here are unmistakable. And the actions of such groups as the 71st Liaison Squadron and the 1st Air Commando Group commanded by Colonels Phil Cochran and

John Alison, forecast the Army’s performance in Southeast Asia twenty years hence. But instead of the flivver plane, it would be the helicopter that would carry the ball for the Army. The old saying is that you have to crawl before you can walk. Well in World War II, the helicopter was crawling; in Korea, it walked. But in Vietnam, the helicopter ran—fast . . . proving a concept that would revolutionize warfare, the Airmobility Concept; a game-changing notion akin to the Wehrmacht’s use of the armored warfare fighting vehicle in a Combined Arms Warfare package that ensured the quick destruction of Germany’s enemies; AKA Blitzkrieg, which proved a vindication of the interwar understanding of the ghastly stalemate of the trenches during 1914-1918, by such theorists as Hans von Seeckt. Likewise, the Airmobility Concept was a vindication of lessons learned during the bloody impasse on the Korean Peninsula.

But it behooves those intimately affiliated with Army Aviation to not only understand their history at this stage, but to thoroughly comprehend it. For Army Aviation is not only a branch of the Army—a one-dimensional exercise in reflection practiced by those who are but of a narrow-minded variety. Rather Army Aviation is an experience, an emotion. We need to celebrate those stalwart types who emerged from World War II and Korea to weather a storm of criticism based on a stigma accepted by short-sighted brother soldiers who chided them for sticking with a segment of the Service which was viewed as nothing more than a dead end. Talk to a few Cub pilots and early helicopter jockeys and that is exactly what they will tell you. The success of Army Aviation, then, was built on those who refused to capitulate to such reactionary thinking and antagonisms. This, then, makes Army Aviation not merely a branch of the United States Army, but . . . a Movement. A movement like the 19th century Carbonari who were wedded to the Il Risorgimento or Unification of Italy. Like the Vietminh led by Ho Chi Minh who fought and later won the unification of Vietnam. Like the United States Marine Corps. Leathernecks, it seems, are not just Veterans or active duty people. They are part of a tradition that is a Brotherhood, one which goes back to the American Revolution, with each generation adding and building that tradition. The Royal Navy can be viewed along similar lines. And that is how Army Aviation must be viewed by its veterans and supporters, such as those of the Army Aviation Association of America. A poverty of such attitude and Army Aviation will not be long for this world. And it is with this idea in mind that this series is dedicated to those early aviators in both Cubs and helicopters, together with their ground crews and all those others who organized the Air Observation Post and its evolution into what is today’s Army Aviation. For without their steadfast perseverance, Army Aviation never would have become that indispensable vehicle of support of the Foot Soldier.

Endnotes

[1] See page 467, Chapter 21, “Grand Strategy and the Washington High Command,” American Military History, edited by Maurice Matloff.

[2] For the invasion of Leyte, October 1944, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger had 202,500 troops in his Sixth Army. See page 10, “Operations,” Leyte, The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II, United States Army Center of Military History, by Charles R. Anderson.

For the invasion of Okinawa, April 1, 1945, Lieutenant General Simon B. Buckner, in command of Tenth Army, had 183,000 soldiers and marines. See pages 21-28, Chapter 1, “Operation Iceberg,” Okinawa: The Last Battle, by Roy E. Appleman, James M. Burns, Russell A. Gugeler and John Stevens.

[3] See page 253, “The Field Artillery Observation Battalion,” Prepared in the Department of Observation, the Artillery School, The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 38, No. 6. December 1948.

[4] See page 279, “Air OPs . . . in New Guinea,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 34, No. 5, May 1944, by Captain Robert M. White, II, F.A.

[5] See page 280, Captain Robert M. White, II, F.A.

[6] See pages 614-616, “Artillery Cubs in Mountain Operations: 33rd Inf. Div. in Northern Luzon,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 35, No. 10, October 1945, by Colonel Ralph MacDonald, F.A.

[7] See page 73, “Biscuit Bombers (Leyte Style),” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 38, No. 2, March-April, 1948, by Major Edward M. Flanagan, Jr., F.A.

[8] “The Operations of the 3rd Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry (11th Airborne Division) in the Advance Through the Mohonag-Anas Pass to the West Coast of Leyte, 27 November-25 December 1944,” 1st Lieutenant Richard V. Barnum, Advanced Infantry Officers Class No. II, Fort Benning, GA.

[9] See page 93, Chapter 4, “Employment,” The Development of Organic Light Aviation in the Army Ground Forces in World War II, by Major Robert S. Brown, USA.

[10] See page 115, “The Most Lethal Plane in the World,” Mr. Piper and His Cubs, by Devon Francis.

[11] See pages 308 and 309, “The Airport,” Behind the Lines: With the OSS in Burma, by Richard Dunlop.

[12] See page 170, Chapter IV, “The War Years: Europe, Pacific and Korea,” The Army Aviation Story, by Richard K. Tierney with Fred Montgomery.

[13] Below is a listing of the six articles chronicling the Air Observation Post in World War II:

1) “80th Anniversary of Army Aviation: Reflections in North Africa,” Looking Back column, August 2022.

2) “80th Anniversary of Army Aviation: Combat Debut: Operation: TORCH,” Looking Back column, November 2022.

3: “80th Anniversary of Army Aviation: Operation: TORCH: Grasshoppers Earn Their Wings,” Looking Back column, December 2022.

4) “80th Anniversary of World War II: Army Aviation: Italian Campaign,” Looking Back column, September 2023.

5) “80th Anniversary of World War II: Army Aviation: France,” Looking Back column, August 2024.

6) “80th Anniversary of World War II: Army Aviation: The Pacific Theater,” Looking Back column, May 2025.

[14] See page 169, “Artillery in Air-Ground Cooperation,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 38, No. 4, July-August 1948, by Lieutenant Colonel Edward S. Berry, F.A.

[15] See page 66 and 69, Chapter Seven, “Sunny Italy,” Box Seat Over Hell, by Hardy D. Cannon.

[16] Pages 18 and 19, Chapter Two, “Needle-Point Air Force,” Sky Soldiers: The Saga of Army Aviation, Vol. 1, by Mark Albertson. Unpublished manuscript.

[17] See page 5, “S-47/VS-316A Helicopter,” Sikorsky Product History, prepared by Vinny Devine.

[18] See pages 6 and 7, “The Development of the Helicopter,” Sikorsky Historical Archives, www.sikorskyarchives.com/tdoth.html

[19] See page 9, Vinny Devine. Consult, too, “Saga of the Eggbeater,” by Mark Albertson, World War II History, pages 8-11, 74, October 2016.

Bibliography

Albertson, Mark, “Saga of the Eggbeater,” World War II History, Sovereign Media, McLean, Virginia, October 2016.

Albertson, Mark, unpublished manuscript, Vol. 1, Sky Soldiers: The Saga of Army Aviation.

Anderson, Charles R., Leyte, 17 October 1944 to 1 July 1945, U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II, Center of Military History, United States Army, CMH Pub 72-27, Washington, D.C., 1994.

Appleman, Roy E.; Burns, James M.; Gugeler, Russell A. and Stevens, John, Okinawa: The Last Battle, World War II, 50th Commemorative Edition, Center of Military History, United States Army, CMH Pub 5-11-1, Washington, D.C., 1993. First published 1948.

Barnum, 1st Lieutenant Richard V., Advanced Officers Class No. 11, Fort Benning, Georgia, “The Operations of the 3rd Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry (11th Airborne Division), in the Advance Through the Mohonag-Anas Pass to the West Coast of Leyte, 27 November-25 December 1944.”

Berry, Lieutenant Colonel Edward S., F.A., “Artillery in Air-Ground Cooperation,” The Field Artillery Journal, Vol. 38, No. 4, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., July-August, 1948.

Brown, Major, Robert S., The Development of Organic Light Aviation in the Army Ground Forces in World War II, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, June 2, 2000.

Cannon, Hardy D., Box Seat Over Hell, Hardy Cannon, San Antonio, Texas, 1985.

Department of Observation, The Artillery School, “The Field Artillery Observation Battalion,” Vol. 38, No. 6, The Field Artillery Journal, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., December, 1948.

Devine, Vinny, “S-47/VS-316A Helicopter,” Sikorsky Product History, Igor I. Sikorsky Archives, sikorskyarchives.com/home/sikorsky-product

Dunlop, Richard, Behind the Lines: With the OSS in Burma, Rand McNally & Company, Chicago, New York, San Francisco, 1979.

Flanagan, Major Edward M., Jr., F.A., “Biscuit Bombers (Leyte Style),” Vol. 38, No. 2, The Field Artillery Journal, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., March-April, 1948.

Francis, Devon, Mr. Piper and His Cubs, The Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1973.

MacDonald, Colonel Ralph, F.A., “Artillery Cubs in Mountain Operations: 33rd Inf. Div. in Northern Luzon,” Vol. 35, No. 10, The Field Artillery Journal, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., October 1945.

Matloff, Maurice, General Editor, American Military History, Army Historical Series, Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1969.

“The Development of the Helicopter,” Sikorsky Product History, Igor I. Sikorsky Archives, www.sikorskyarchives.com/tdoth.html

Tierney, Richard with Montgomery, Fred, The Army Aviation Story, Colonial Press, Northport, Alabama, 1963.

White, Captain Robert M., F.A., “Air OPs . . . in New Guinea,” Vol. 34, No. 5, The Field Artillery Journal, The United States Field Artillery Association, Washington, D.C., May, 1944.