By Mark Albertson: It is fitting that we, at Army Aviation, recall a day that changed the complexion of this Nation; irrevocably changed the course of the 1939-1945 conflict and, helped to determine a new global balance of power by 1945; and in addition, helped to set the stage for the founding of Army Aviation some six months later . . . and that event was, the Day of Infamy, December 7, 1941.

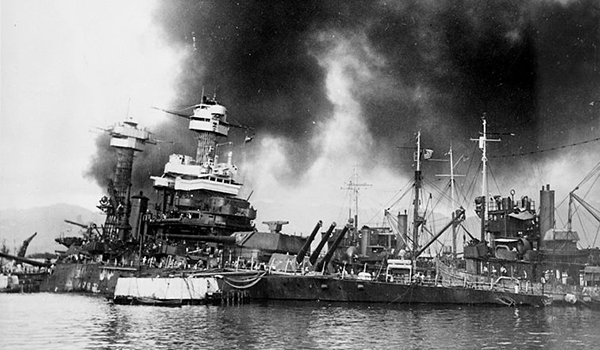

Battleships sunk, left to right, West Virginia (BB-48), Tennessee (BB-43) and ill-fated Arizona (BB-39).

0753 hours, Sunday, December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the Pacific Fleet anchorage at Pearl Harbor. In essence, the Day of Infamy merely codified this Nation’s entry into Man’s Greatest Conflict. U.S. destroyers had already been swapping depth charges and torpedoes with German U-boats for months, since the Navy had been escorting convoys halfway across the Atlantic. In addition, Marine Colonel Leo D. Hermle’s 6th Marine Regiment, nucleus for the 1st Marine Brigade Reinforced—194 officers and 3,714 men—had arrived at Iceland on July 7, 1941. The first U.S. Navy task force employed for foreign service in World War II occurred five months before Pearl Harbor. This was done to relieve the British garrison, where the Tommies were on their way to a more active front in North Africa.

Nakajima B5N “kate” torpedo plane. These aircraft savaged Battleship Row on December 7, 1941.

The Japanese attack—planning for which began in January 1941—featured six aircraft carriers: Akagi [flagship], Kaga, Hiryu, Soryu, Shokaku and Zuikaku, all carrying the cream of Japanese naval aviation. The attack itself was based on the British strike against the Italian fleet at Taranto the previous November. A single carrier, HMS Illustrious, loosed 21 aircraft against the Italian anchorage. Fleet Air Arm efforts caused one battleship to settle in the harbor mud and damaged two others, sidelining them for months. However, in Berlin, an assistant air attache assigned to the Japanese embassy, a Lieutenant Takeshi Naito, researched the British attack and forwarded his notes to Tokyo. And on January 7, 1941, Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto wrote to Rear Admiral Takijiru Oikawa, “A conflict with America . . . is inevitable.” He urged an attack on Pearl Harbor, following up with, “. . . decide the fate of the war on the very first day.(1)

Pearl Harbor trivia: During World War II, the Allies accorded Japanese aircraft with codenames: Fighters were given male names. For instance, the famed Mitsubishi A6M Zero was the “Zeke.” The Kawasaki Ki-61 Hien was the “Tony.” Conversely, bombers were given female names. The Aichi D3A dive bomber was known as the “Val.” The Mitsubishi G4M medium bomber was known as the “Betty.”

Commander Minoru Genda wrote the feasibility study for the attack. He would serve as Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s air advisor aboard the flagship Akagi. Genda’s friend and colleague, Commander Mitsuo Fuchita, organized the attack waves, personally leading the initial assault. He would, without success, press the more cautious Admiral Nagumo, for a third attack against the port and dock facilities and oil tank farms. After the war, Mitsuo Fuchita would convert to Christianity and become a Protestant minister.

The aforementioned Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo offers an intriguing command dilemma for the Japanese. He was a battleship, cruiser, destroyer man, not a proponent of airpower. He also did not get on well with Admiral Yamamoto. The logical choice to command the Pearl Harbor attack force should have been Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, a vigorous proponent of airpower. Nagumo won the nod because of his duration of service as a vice admiral versus Ozawa.(2) But, of course, the question must be raised: If Ozawa had been in command of the Japanese carrier force on December 7, would a third attack wave been launched? Keep in mind if such had been done and the Pacific Fleet tank farm had been destroyed, the U.S. Navy would have been refueling ships back in San Diego.(3)

Pearl Harbor posed problems for torpedo launching because of its shallow depth, some 40 to 50 feet deep. When launched from aircraft, torpedoes plunged some 65 feet or more before levelling off to begin their deadly runs. The Japanese solved this problem by affixing wooden fins to their Type 91, Model 2, torpedoes. The fish then plunged only 39 feet. The results of Japanese ingenuity speak for themselves.(4)

Pearl Harbor trivia: About a week after the Japanese attack, Major William Wallace Ford was ordered to report to Washington to begin planning for the Air Observation Post concept. Ford was joined by Major Gordon J. Wolf, an attorney in corporate law who at one time represented the interests of Aeronca Aircraft Corporation. Major Rex Chandler, a radio/communications expert whose talents with same would prove a boon to Army Aviation, was a ground officer who believed in the Air OP concept. And Colonel Rex Beasley out of the Office of the Chief of the Field Artillery, who rounded out the planning group.

Pearl Harbor trivia: About a week after the Japanese attack, Major William Wallace Ford was ordered to report to Washington to begin planning for the Air Observation Post concept. Ford was joined by Major Gordon J. Wolf, an attorney in corporate law who at one time represented the interests of Aeronca Aircraft Corporation. Major Rex Chandler, a radio/communications expert whose talents with same would prove a boon to Army Aviation, was a ground officer who believed in the Air OP concept. And Colonel Rex Beasley out of the Office of the Chief of the Field Artillery, who rounded out the planning group.

The Japanese attack lasted 110 minutes. In that time, eight battleships were sunk or damaged, with Arizona (BB-39) and Oklahoma (BB-37) as total losses. Three light cruisers and four destroyers were damaged. A minelayer was sunk and two auxiliaries were heavily damaged, one of which capsized. 169 aircraft were lost, 92 Navy and 77 Army, with another 150 damaged. 2,403 Americans were killed with another 1,109 wounded. In less than two hours, 16 Medals of Honor, 51 Navy Crosses, 53 Silver Crosses, four Navy and Marine Corps Medals, a single Distinguished Flying Cross, four Distinguished Service Crosses, one Distinguished Service Medal and three Bronze Stars were awarded. And the cost to the Japanese? Nine fighter planes, five torpedo planes and 15 dive bombers; one fleet submarine and 5 midget subs and 185 men.(5)

Pearl Harbor trivia: Of 2,403 Americans killed on December 7, 1941, 1,177 died on the Arizona.

However the strategic significance of Pearl Harbor is not that it marks America’s official entry into a global conflict that had been raging for more than two years; for in reality the war was not a global conflict until America was an official participant; this is because the attack on Pearl Harbor linked the Pacific with the Atlantic in producing a worldwide struggle. It is the month of December that is of significance. On the night of December 4-5, 1941, General Georgi Zhukov launched a huge counterattack against Hitler’s frozen Wehrmacht. On a front more than 600 miles wide, the Nazis were pushed back from the gates of Moscow, retreating upwards of 150 miles or more. Two days later, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. A war that had been, for the most part, a European struggle, was now a global conflict. A global conflict which would prove beyond the resources of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan. Only two nations had the capacity to wage conventional war on the scale required starting January 1942, the United States and the Soviet Union, the globe’s number 1 and number 2 industrial powers. These two monoliths possessed the three aspects required to wage modern war at this stage of the Industrial Revolution:

Battleship California (BB-44) sinking at Pearl Harbor.

- Large industrial infrastructures. America’s economic muscle needs no explanation here. But Stalin’s program of forced industrialization beginning in 1928 would prove to be one of the biggest secrets for Allied victory in World War II. For example, Chelyabinsk, in the Urals, would become the greatest tank-producing combine in the world. The Soviets engaged the German Army in the decisive land campaign of the entire war. It will be the Red Army that will win the land war; a victory this army would accomplish largely on its own. For Lend-Lease would amount to less than 10 percent of the total Soviet war effort.

- Large populations, necessary to replace losses. Again the Soviets come to mind here. In 47 months of the most brutal combat of the Second World War, 1 in seven Soviets would die in defeating the invading Nazis, some 25,000,000 dead. According to the Navy Department, American dead in World War II totaled 405,399.

- Indigenous supplies of oil. Oil revolutionized war during the 1914-1918 conflict; will dominate war after 1939. The United States and the Soviet Union had it, and by comparison to the Axis Powers, in abundance. During World War II, the United States would supply 6 of every 7 barrels of oil burned by the Allies in World War II [exclusive of the Soviets].(6)

- Pearl Harbor, together with the Soviet victory at Moscow, renders December 1941 as the turning point of the war. Standout engagements such as Stalingrad, Midway or El Alamein, are pivotal battles on their immediate fronts; but their importance is that they appear in the wake of December 1941 as integral parts of a progression of engagements which help to decide the outcome of the war. For after December 1941, the European colonial powers, which for centuries had determined the global dynamics of power, were now being overtaken by the two nations which would be the big winners of the war in 1945, the United States and the Soviet Union. And with regards to the former, such is the essence of December 7, 1941.

Pearl Harbor trivia: On the evening of December 7, 1941, Winston Churchill, upon learning of the Japanese attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet, observed, “I thought of a remark which Edward Grey had made more than thirty years before—‘that the United States is like a gigantic boiler, once the fire is lighted under it, there is no limit to the power it can generate.’ Being saturated and satiated with emotion and sensation, I went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.”(7) Mr. Churchill clearly understood that with America’s power and might behind them, victory for the Allies was merely a matter of time.

End Notes

(1) See page 20, Chronology, Pearl Harbor, by Carl Smith, 2001.

(2) See page 53, chapter 6, “The Attack Force,” Pearl Harbor, by Edwin P. Hoyt, 1991.

(3) The Navy fleet reserve at Oahu boasted 4,500,000 barrels of oil. See page 56, chapter 5, “Day of Infamy,” Pearl Harbor, by H.P. Willmott.

(4) See page 30, Smith.

(5) See pages 75 and 78, Smith.

(6) See page 49, “Our Lethal Dependence on Oil,” Proceedings, Lieutenant (jg) Douglas R. Marsh, USN, June 2010. In addition, shortly before his death, Franklin D. Roosevelt understood the decisive nature of oil. And with the upcoming strategic competition with Moscow, it was imperative that the United States seek to control oil, whether those resources were domestic or of the foreign variety. And on Valentine’s Day, 1945, FDR met with Abdul Aziz Ibn-Saud aboard the heavy cruiser Quincy (CA-71) off Bitter Lakes, Egypt, where the two consummated the deal, U.S. military protection for Saudi Arabia versus preferential access to the Kingdom’s crude, a major building-block of American foreign policy since 1945.

(7) See page 700, “Pearl Harbor,” Part 25, History of the Second World War, 1973.

Sources

Brown, David, “Val and Kate,” Sea War in the Pacific, Marshall Cavendish Ltd., New York, NY., 1976.

Churchill, Winston S., The Grand Alliance, Volume 3, The Second World War, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Mass., 1951.

Hoyt, Edwin P., Pearl Harbor, Avon Books, New York, NY., 1991.

Lowrey, Dr. Thomas P. and Wellham, Lieutenant Commander John W.G., DSC Royal Navy (Ret.), The Attack on Taranto: Blueprint for Pearl Harbor, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 1995.

MacIntyre, Donald, Aircraft Carrier: The Majestic Weapon, Ballantine’s Illustrated History of World War II, Weapons Book, No. 3, New York, NY., 1968.

Marsh, Lieutenant (jg) Douglas L., USN, “Our Lethal Dependence on Oil,” Proceedings, United States Naval Institute, Annapolis, MD., June 2010.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, The Battle of the Atlantic,1939-1943, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Castle Books, Edison, NY., 2001. Originally published in 1947.

Munson, Kenneth, Aircraft of World War II, Ian Allen, UK, 1962.

“Pearl Harbor,” Part 25, History of the Second World War , Marshall Cavendish USA Ltd., New York, NY., 1973.

Schofield, Vice Admiral B.B., The Attack on Taranto, Sea Battles in Close Up, No. 6, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD., 1973.

Smith, Carl, Pearl Harbor, Osprey Publishing, Ltd., Oxford, UK., 2001.

Whitley, M.J., Cruisers of World War II: An International Encyclopedia, Arms & Armour Press, London, 1996.

Willmott, H.P., Pearl Harbor, Galahad Books, New York, NY., 1981.